Despite nearly $1 trillion flowing into America’s K–12 education system, student outcomes remain stubbornly stagnant, raising urgent questions about how effectively these funds are being used.

According to a new analysis by the Reason Foundation, total spending on public K-12 schools — from local, state, and federal sources — reached $946.5 billion in 2023. When adjusted for inflation, that amounts to $20,322 per student, up from $14,969 per student in 2002 or a 35.8 percent increase over two decades, a substantial boost in resources for public education.

Average reading results on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) are lower than they were when the tests were first administered in 1992, and math scores have not yet rebounded to pre-COVID levels. Even pre-COVID student outcomes showed bouts of regression and were trending downward. Internationally, a number of countries have higher post-pandemic achievement results compared to their pre-COVID results, but this has not been the case for the United States.

Minnesota spending

Minnesota sits near the middle-to-upper tier nationally in per-pupil spending, coming in at $19,542 in inflation-adjusted per student funding, according to the Reason Foundation. This is a 25 percent increase from 2002 levels, despite claims from special interest groups that funding hasn’t kept pace with inflation. (Look for more on this topic in an upcoming paper.)

Inflation-adjusted K-12 benefit spending and growth (teacher pensions, health insurance, and other expenses) is at $3,367 per student, up nearly 51 percent since 2002. A primary driver of rising benefit spending is teacher pension debt, according to the Reason Foundation.

For years, states have failed to set aside enough money to cover the pension benefits promised to teachers, resulting in hundreds of billions of dollars in unfunded liabilities (i.e., the difference between the total pension benefits owed to teachers and the dollars available in pension funds). Today, this means that more K-12 education funding must be used to cover pension costs, even while many states have reduced benefits for teachers, rather than in classrooms.

Minnesota’s teacher pension system is at $7.1 billion in unfunded accrued liability, and its funded ratio is at 79.9 percent. Put another way, only 80 cents on the dollar is available to pay teacher benefits. The fund also continues to run a contribution deficiency. This means that actual contributions once again fail to meet the required contributions necessary to fully fund the pension plan.

Hiring patterns

Over the last 20 years, Minnesota district hiring patterns have tended to prioritize non-teaching roles, and bureaucratic expansion is experiencing higher percentage growth compared to student enrollment growth patterns.

Since 2002, K-12 public school enrollment has increased 2.2 percent. Meanwhile, K-12 public school non-teaching staff has increased just under 29 percent (28.9 percent) over that same time period, according to the Reason Foundation’s calculations.

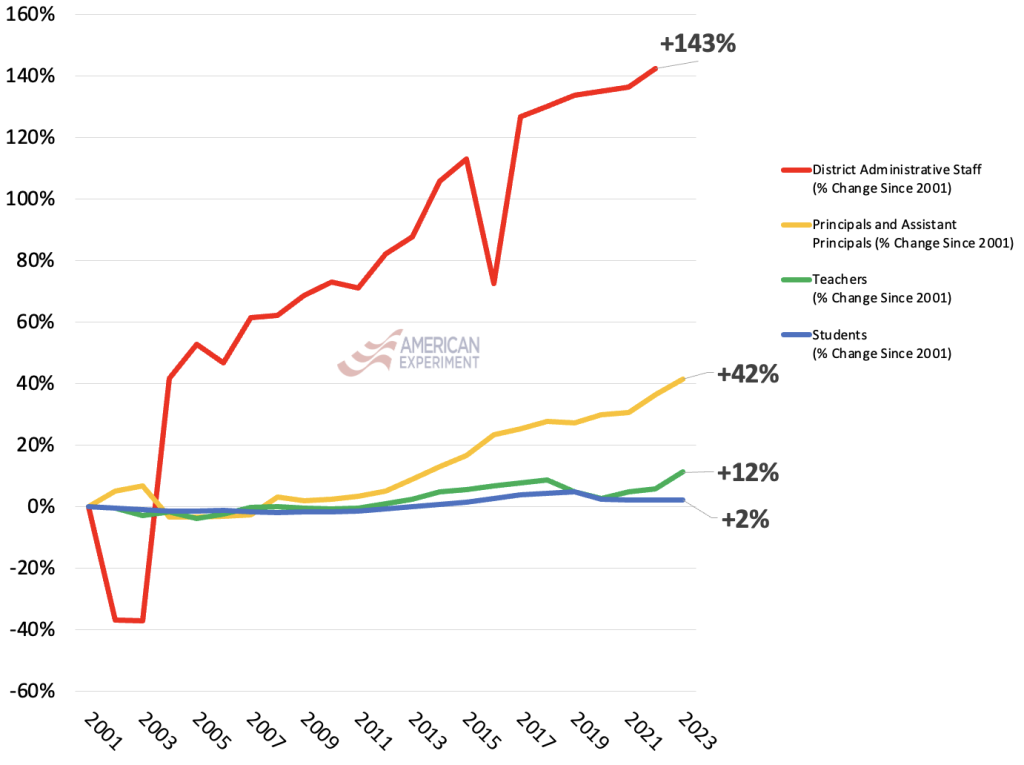

The Reason Foundation’s report doesn’t offer a breakdown of growth among specific non-teaching positions, but I have calculated that for Minnesota here and here. Since the 2001-02 school year, principal/assistant principal growth is up 42 percent. School district administrative staff is up 143 percent. Teacher growth over that same period increased 12 percent.

Based on national projections from the National Center for Education Statistics showing a 5.3 percent decline in public school enrollment between 2024 and 2032, the Reason Foundation warns that “current staffing levels are unsustainable.”

School closures are on the horizon in places like Boston, Houston, Seattle, and Oakland, but it will also be important to reduce staffing to levels that match enrollment.

Locally, both the Minneapolis and Robbinsdale school districts are facing potential school closures, according to reporting by my colleague Josiah Padley. (Remember when the Minneapolis school district used non-recurring money to add 400 jobs despite years of shrinking enrollment? Or the Robbinsdale school board admitting it “misstepped” when one-time dollars were used to hire positions despite decreased enrollment?)

Growth in Administrative Staff, Principals, Teachers, and Students

in Minnesota Public Schools (% Change Since 2001)

Minnesota learning outcomes

The persistent push in Minnesota for higher education budgets continues to leave a fundamental question unanswered: Why aren’t students learning more, despite all the new spending?

More than half of students remain below grade-level proficiency in math and reading, and despite the state’s graduation rate reaching an all-time high, high school achievement is at an all-time low. In fact, student outcomes in the state were falling even before COVID-19 and despite increased funding levels. The percentages of students scoring below basic in 4th- and 8th-grade reading are at all-time highs.

This has real implications for students, not only academically but economically, as well.

Meanwhile, parents who want schooling alternatives and better access to those alternatives face resistance from the same political forces demanding more taxpayer dollars for the status quo.

Reform, not bigger bureaucracy

Real challenges exist for Minnesota’s education system — COVID relief funds have expired, enrollment is declining in many districts, and achievement isn’t responding to increased education dollars.

While Minnesota was the only state to post an inflation-adjusted increase in teacher salaries between 2020 and 2022, according to the Reason Foundation’s calculations, the state still struggles with mediocre educational outcomes and follows the same pattern seen nationally: more money, more bureaucracy, more administrative layers, and very little improvement in academic performance.

If Minnesota wants genuine improvement, it must break from its past track record of education reforms. Minnesotans deserve better than another round of “spend first, explain later” education policy.

It’s time for the state to prioritize empowering parents with more school choice, rewarding high-performing teachers (not just longevity), cutting administrative bloat, and better holding districts accountable for producing real academic gains.