The Revenue-Neutral law that went into effect in 2021 is helping many Kansans, with nearly two-thirds of taxing entities deciding NOT to raise property taxes this year. It requires cities, counties, school districts, and other local taxing authorities to notify taxpayers if they want to collect more property tax revenue the following year, hold a public hearing, and then take a recorded vote to raise taxes.

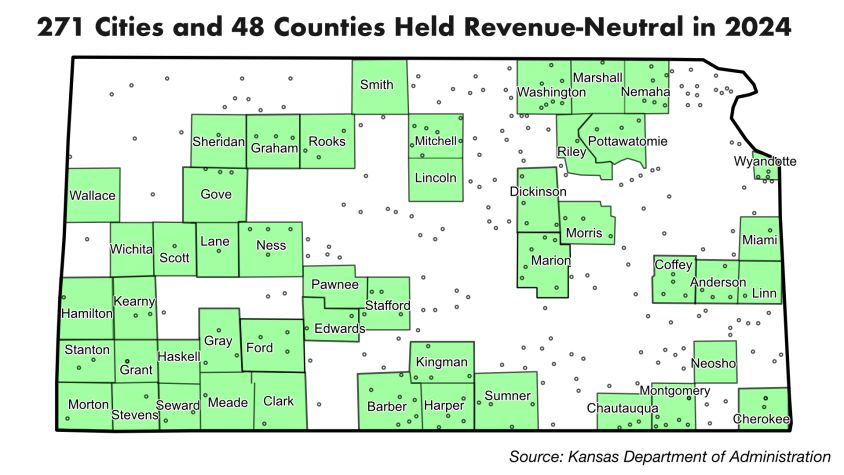

More than 50% of cities, counties, school districts, and other authorities decided NOT to exceed revenue-neutral in the first year. Now, it’s up to 62% holding revenue-neutral, and it’s not just the small entities. Initially, 38 counties held revenue-neutral. Now it’s up to 48 counties, nearly 300 cities, dozens of school districts, and hundreds of townships.

The map below just reflects the cities and counties where elected officials held the revenue-neutral rate in 2024 for taxes owed this year. Taxpayers in those cities and counties would be paying more this year without revenue-neutral, and state legislators must keep it in place.

Many cities, counties, and school districts have been lobbying the Legislature to abolish revenue-neutral. Local governments know the revenue-neutral law is hindering their desire to raise property taxes, and sadly, they don’t like having to honestly tell taxpayers how much their taxes are being increased. Kansans need their state representatives and state senators to continue standing with taxpayers and keep revenue-neutral in place.

Revenue-neutral helps, and more reforms are needed

Unfortunately, some elected officials are taking advantage of appraised value increases.

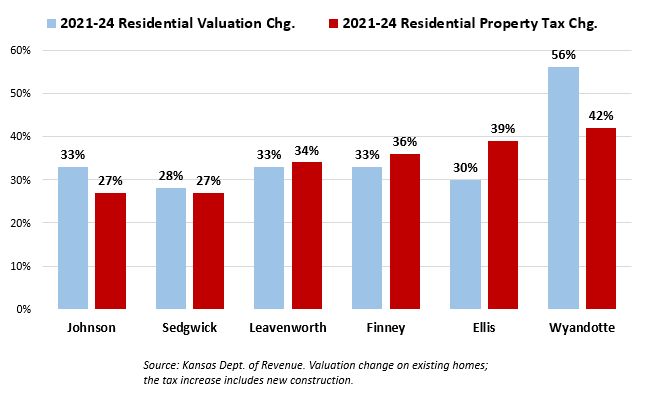

Since the law took effect three years ago, the average homeowner saw their appraised value increase by more than 30%, and some local officials used that to impose outrageous property tax increases. Some people are literally being taxed out of their homes.

For example, elected officials in Wyandotte County took advantage of a 56% valuation increase to raise residential property taxes by 42% over three years. The residential tax increase in Leavenworth, Finney, and Ellis counties exceeded 30%, and residential property taxes jumped 27% in Johnson and Sedgwick counties. Linn County has the highest residential valuation increase of 66%, and a 45% tax increase on homes.

This is an affordability issue that state lawmakers must address. Regardless of whether the valuations are accurate, many homeowners cannot afford the increase without cutting back on essentials or having to sell. Local officials who imposed unaffordable tax increases are to blame, but state legislators control transparency and the methodology for raising property taxes.

Turnout at the Johnson County revenue-neutral hearing was so great that the meeting had to be moved to a larger facility. Commissioners ignored residents’ pleas and questions, like, ‘We’re cutting back, why aren’t you?’ and voted to raise taxes by 6%. Johnson County’s spending increased far in excess of inflation and population growth, and commissioners have hundreds of millions of dollars in cash reserves that could be used to avoid a tax increase, but they raised taxes anyway.

The House and Senate passed different versions of a constitutional amendment that would protect taxpayers from unaffordable, double-digit tax increases. The Senate approved a 3% annual limit on appraised values for all classes of real estate and mobile homes. The House version applied only to residential and commercial real estate and mobile homes, and used a rolling average of annual increases to cap taxable assessed values. The number of years in the rolling average would be set by the Legislature following passage of the constitutional amendment.

Limiting the increase in taxable assessed valuation, as proposed by the House, is better than the Senate limit on appraised values. Property is appraised at its theoretical market value, but taxes are based on assessed values, with different assessment ratios for each class of real estate. For example, residential property is assessed (taxed) at 11.5% of appraised value, so a $200,000 home has a taxable basis of $23,000. The House version allows property to continue being appraised at market value while limiting the increase in the taxable portion of the property.

The Senate’s 3% fixed annual limitation methodology is better for taxpayers than the House’s rolling average, however, given the likelihood that appraised values will increase at a much higher rate.

Hopefully, the House and Senate will compromise come January with the best of both bills: a fixed annual limit on the increase in taxable assessed values that applies to all real estate classifications and mobile homes.

Limit property tax increase without voter input

Limiting the increase in taxable assessed values may prompt some elected officials to boost mill rates, and the Legislature can mitigate that temptation by making it harder to impose large tax increases without some form of voter input.

Legislators could stipulate that increases exceeding the lesser of inflation or 4% can only happen with voter approval at an August election. Alternatively, a property tax revenue increase above 4% could require a unanimous or super-majority vote of the elected body. Protest petitions are another option; voters could veto the tax increase by gathering enough signatures on the petition within a specified time frame.

Excuses don’t pay property tax bills

Some legislators say local government spending is the problem, and they are right. However, that shouldn’t be used as an excuse to wait for city council members, county commissioners, and local school boards to solve the problem they created. Local government entities are creations of the Legislature, and legislators have the legal authority and moral obligation to provide relief for taxpayers.

Kansans need help now. Taking years trying to find a better system is effectively saying, “I’m sorry, ma’am; you will have to sell your home if you can’t afford the property tax, because we need more time to think.”

This is an urgent matter of affordability, and legislators will hopefully reach a good compromise soon so they can pass property tax relief when the next session begins in January.