Illinois ranked No. 1 for spending per student on higher education in 2024, paying more than double the national average. Declining enrollment, poorly structured finances, growing pension payments and bloated administration have driven up costs.

Illinois spends double the U.S. average per full-time higher education student, yet 106,375 fewer students want to attend its public community colleges and state universities than 15 years ago.

Pensions, administrative bloat and a poor funding formula are mainly to blame.

Illinois ranked No. 1 in the U.S. for higher education spending per full-time student in fiscal year 2024, spending $25,529 per student. That was double the national average and over $4,400 more per student than the No. 2 state: Wyoming, which had only about 8% of the students Illinois supports.

That translates to Illinois spending the most in the nation per full-time student at public two-year institutions and the second most in the U.S. per full-time student at public four-year institutions.

But all that government money has failed to make Illinois higher education more attractive to students. Enrollment at two- and four-year institutions has dropped from 368,019 in 2009 to 261,644 in 2024, according to the State Higher Education Finance report.

As spending by the state on higher education has climbed, so has the cost of tuition. Illinois’ in-state tuition for a public university now ranks No. 6 in the nation. It is the highest in the Midwest, rewarding Illinois students with more affordable options when they cross state lines.

Research in 2021 showed nearly 48% of Illinois’ four-year, college-bound students chose schools elsewhere, with the top picks being public universities in neighboring states where tuition was cheaper. They took their knowledge, income and tax dollars with them – often for good.

So why are Illinois taxpayers being forced to spend more on higher education when their schools are serving fewer students? And why does all that government spending fail to keep Illinois tuition from being among the highest in the nation?

State pensions, administrative glut and a poor funding model are mainly to blame at the state’s 12 public universities and 48 community colleges.

While the University of Illinois-Urbana and University of Illinois-Chicago have seen continuous enrollment growth, attendance at nearly every other university is declining. Similarly, all but three of Illinois’ community colleges also reported lower attendance last year than in 2009. But the proportion of higher education dollars provided to them remains fixed.

State appropriations for higher education are based on historical precedent, not on enrollment or performance. Each university receives the same percentage increase year after year, regardless of how inefficiently they spend or how poorly they attract students – effectively punishing responsible schools.

These state operating appropriation estimates for fiscal year 2025 exclude appropriations for the State Universities Retirement System, grants and overhead costs and represent funding for all enrolled students, including part-timers.

Altogether, when considering full-time enrollment, grants, insurance and contributions to SURS, Illinois’ grand total hits the $25,529 mark and ranks No. 1 in the nation in per-student higher education spending.

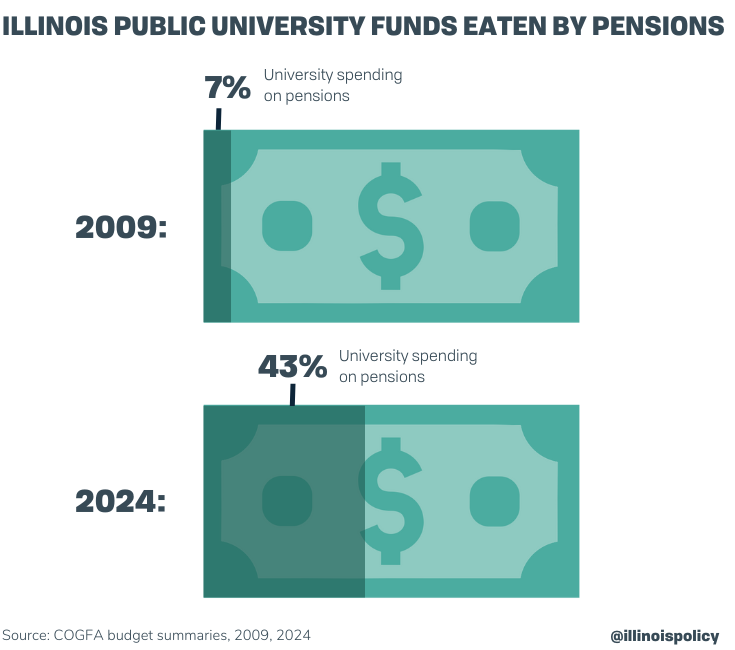

Public pensions for university retirees is a major culprit in the inordinately high cost. About 43 cents of every state higher education dollar from general funds goes to fund pensions instead of instructing students. That’s up from just over 7 cents in fiscal year 2009.

But even without considering the high costs of state university pensions, which totaled over $1.9 billion in fiscal year 2024, Illinois still spends among the most in the nation on higher education per student thanks to other high overhead costs such as administration.

A substantial portion of university funding – more than 10% – is spent on administrative bloat, not students or faculty. In fiscal year 2024, Illinois’ public universities spent about $428.8 million in state-appropriated funds on administrative expenses.

In total, state higher education spending reached $4.46 billion in fiscal year 2024, consuming nearly 9% of all state spending. That’s compared to about 7% of the state budget in 2009. Illinois spending increased about $2 billion as enrollment dropped by 106,375 during that period.

“We’re spending so much taxpayer money on these schools, and I think an evaluation of where the money is going is important,” said state Rep. David Friess, R-Red Bud, who serves on the Illinois House Higher Education Committee. “We need a transparent account of all the money the universities spend and all the taxpayer money that’s raised to justify the ever-increasing cost of going to school for students.”

When students can’t get into their top choice, such as the University of Illinois, many leave the state instead of settling for a shrinking regional university. And with future Illinois enrollment predicted to plummet by about one-third by 2041, attending the right school could become even more expensive for in-state students.

The system is not aligned with the needs of today’s students or the state’s future. The result is more subsidies for struggling institutions, fewer attractive choices for students and higher costs for taxpayers.

Friess also blamed the schools for adding expensive facilities in an effort to attract students and also adding degree requirements that keep them in school longer and drive up student costs.

“University should be career focused, like apprenticeships,” Friess said. “If you want to be an electrician or a plumber or a carpenter, you don’t need to spend four years at a university. You can go to a trade school, learn a trade and go to work within 12 months. If colleges really wanted to get people out of school and into the workforce sooner, I think they could, too, while saving more money for the universities and students.”

Illinois must take a strategic, statewide approach to how it nurtures young people after high school to become productive community members. Fixing university funding means controlling pensions, reducing administration and changing the funding formula to reward enrollment. Fixing workforce training means investing in it and encouraging that choice.

Otherwise, we’ll keep waving goodbye to our children and grandchildren after high school graduation.