Colorado politicians who whine about the restrictions in TABOR should read the original Colorado Constitution to learn how real tax limitation works.

This article first appeared on January 26, 2026 in Complete Colorado.

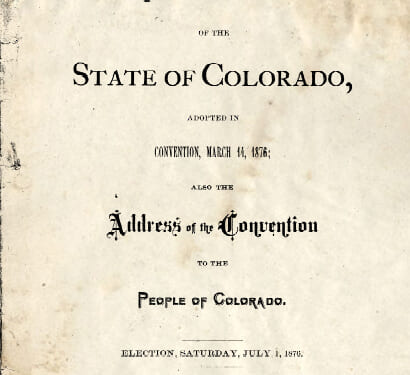

This year marks the 150th anniversary of admission of Colorado into the Union. It is also the 150th anniversary of Colorado’s state constitution.

That document, as originally ratified, was an extraordinary testament to human freedom.

The Colorado constitutional convention met from December 20, 1875 to March 14, 1876. Voters approved the convention’s proposal in a July 1, 1876 referendum, and it became effective exactly one month later through a congressionally-authorized proclamation by President Ulysses S. Grant.

The Colorado Constitution served as a model for some states later admitted to the Union. For example, Montana’s 1889 constitution was strikingly similar to its Columbine State predecessor.

The Colorado Constitution was notable for its trail-blazing provision authorizing female suffrage. But the spirit of liberty pervaded the entire document.

Exemplifying that spirit were the document’s financial rules. Unlike today’s “progressive” kleptocracy, Colorado’s founders believed that government was a fiduciary trust, obligated to protect liberty and deliver basic services at the lowest reasonable price. Their charter featured limitations on taxes, spending, and debt far tighter than those in the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights (TABOR), which did not become part of the constitution until 1992.

Restrictions on taxes

Colorado politicians who whine about the restrictions in TABOR should read the original Colorado Constitution to learn how real tax limitation works.

Article X, entitled “Revenue,” authorized only one kind of statewide tax: the property tax. There were no impositions on sales, income, businesses, or anything else. Moreover, the level of property taxes was closely controlled. The constitution initially limited them to six mills (tenths of a cent) on each dollar of assessed valuation. The document mandated a phased drop to two mills as the tax base grew. Thus, in today’s terms, the owner of a $400,000 house could pay no more than $800 in state taxes. And no other state levies whatsoever.

Some other states followed Colorado’s lead in limiting taxes. For example, the North Dakota constitution (1889) limited property levies to four mills per dollar of assessed valuation, while Idaho charter (1890) limited them to ten mills. Utah (1895), after a transition period, authorized only four. Montana (1889) initially permitted only three mills, with a mandate that they later drop to one-and-a-half. However, Montana also permitted corporate franchise taxes.

In Colorado, there was only one way to exceed the constitutional cap on property taxes, and that was by a vote of those electors who actually paid them. Colorado’s framers did not want people who did not themselves pay raising the burden on those who did.

As most readers know, politicians manipulate voters and contributors by granting targeted tax exemptions to favored interests. These sometimes are called “tax expenditures.” The framers of Colorado’s constitution foresaw and forbade this baleful practice: They banned all exemptions except for a few itemized religious and charitable purposes.

Restrictions on spending

Tax limitation was not enough. The 1876 constitution also contained rules to prevent waste. Article X, Section 7 banned the use of state funds to subsidize local government. It provided: “The general assembly shall not impose taxes for the purposes of any county, city, town, or other municipal corporation, but may, by law, vest in the corporate authorities thereof respectively the power to assess and collect taxes for all purposes of such corporation.”

In other words, local people would bear the expenses of local government. They could not overspend and then look to state taxpayers to relieve them of responsibility for their misconduct.

The constitution contained other notable spending restrictions as well. For example:

* In not just one but in two places the constitution required the state to operate on a balanced budget (Article X, Sections 2 and 16).

* A “general appropriations” bill could make multiple appropriations, but could do nothing else. Other appropriation bills were limited to one subject.

* The constitution banned pay raises for a public officer during his term of office.

* It also banned compensation to employees and contractors beyond that contracted for.

* It required competitive bidding for state contracts.

* It prohibited appropriations to private parties. In other words, it banned the practice of subsidizing private persons and entities with government funds.

* It specifically proscribed aid to private companies.

Restrictions on debt

Three decades before the Colorado Constitution was drafted, several states had gone bankrupt from excess spending and debt. Accordingly, the Colorado framers inserted tight restrictions on public debt at both the state and local levels.

The restrictions included limits on how much debt could be incurred. The limits were expressed in dollar amounts and in mills per dollar of assessed valuation. They also specified the maximum rate of tax that could be imposed to retire debt. Finally, they limited what the state could do with borrowed money.

Total state debt could not exceed three-fourths of a mill for each dollar of taxable valuation. Debt spent on public buildings could not exceed half a mill. Most state debt was capped at $100,000—about $3 million in 2026 dollars. Further debt was limited to financing public buildings, but only if approved by a vote of the people.

The Colorado Constitution banned the current practice of using public debt to reward special interests. Specifically, it prohibited state debt “except to provide for casual deficiencies of revenue, erect public buildings for use of the State, suppress insurrection, defend the State, or, in time of war, assist in defending the United States.” The phrase “casual deficiencies of revenue” might seem like a major loophole, but it was not: The balanced budget requirement prevented any but brief shortfalls.

Similarly, the constitution barred the state from using its borrowing power to promote “economic development” and “affordable housing” boondoggles.

The constitution imposed similar debt restrictions on local government.

What happened?

In the years since 1876, Colorado’s constitution has been severely mangled. Part of the damage has been inflicted by ill-advised constitutional amendments promoted by campaigns heavily funded by special interests.

But as my colleague Dave Kopel has documented, much of the damage was inflicted without any popular input at all: Over the years, unscrupulous judges have weakened or nullified the constitution’s safeguards by ignoring or distorting its plain language. The enactment of TABOR in 1992 was an effort to repair some of the judicial damage, but in the ensuing years the courts have largely gutted TABOR as well.

Fortunately, we still have access to copies of Colorado’s original constitution. So we can read it, appreciate it, and reflect on how much we have lost. You can access it yourself here.