The Trump Administration wants to make housing affordable. This is commendable. Unfortunately, among the litany of proposals, solutions that truly address what ails the housing market are missing.

Allowing buyers to use their 401(K) savings for a down payment, for instance, is a demand-side fix that won’t increase housing supply. The same is true of directing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy $200 billion in mortgage-backed securities to lower mortgage rates. If anything, increasing housing demand while supply remains constrained could lead to even higher prices.

Banning corporate or institutional landlords, while superficially appealing, will only divert attention from what truly needs fixing: stringent regulations and fees that prevent and delay housing development.

Econ 101: Demand and Supply

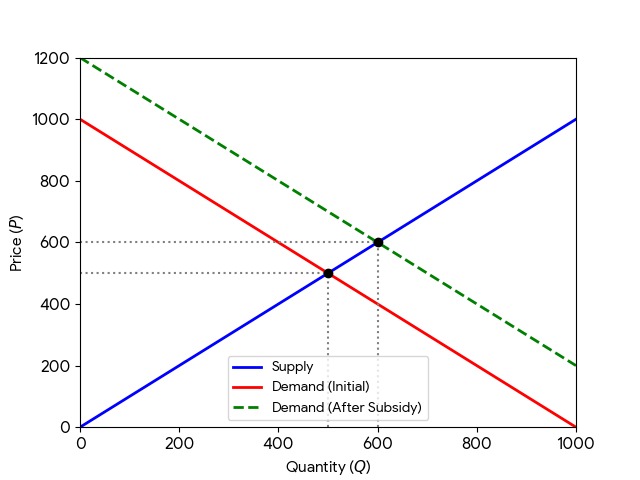

As with any good or service, the price of housing is determined by the interaction between demand and supply. Consider a market (in Figure 1) where demand and supply intersect at a market-clearing price of $500 (blue and red lines). An infusion of cash, such as 401(k) savings in this case, will shift the demand curve to the right. As a result, the new demand curve intersects the (old) supply curve at $600.

That is, without addressing supply, increasing demand merely intensifies competition among buyers, raising prices.

Figure 1: Demand and Supply

What would increasing housing supply look like?

State and local governments, but especially the latter, have enacted various mandates that delay and increase the cost of housing development. These include zoning restrictions, land use rules, park fees, and aesthetic mandates.

Multifamily housing, even of moderate density, is illegal to build in commercial zones and large swaths of residential-zoned areas of some Minnesota cities. But even in places where it is permitted, it is subject to stringent height and density restrictions.

While cities like Minneapolis and St. Paul have enacted some reform, issues remain.

Minneapolis liberalized zoning regulations with the 2020 passage of the Minneapolis 2040 plan. This legalizes denser housing — such as triplexes — in many parts of the city previously restricted to single-family housing. The city, however, requires a maximum Floor Area Ratio (FAR) of 0.5 for single-family zoned lots — a law passed in 2007, which means that the total floor area of a housing unit must not exceed half the square footage of the lot it is built on. This, in addition to other restrictions such as height limits, renders triplexes impractical despite being legal to build. While developers could seek variances, that discretionary approval process is uncertain, costly, and time-consuming.

In a 2024 report, the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis found that 7 out of 10 Twin Cities Suburbs it surveyed required more than 1 parking space per multifamily housing unit.

The estimated cost of parking spots ranged from $3,000 to $10,000 per surface lot space and $30,000 to $50,000 per structured spot.

Park fees also ranged from $1,500 to $8,000 per housing unit.

How corporations really affect the housing market

According to research,

Institutional investors, defined as those owning 100 or more homes in their portfolios, own less than one percent of the single-family housing stock nationally and only about three percent of single-family homes for rent.

Additionally,

Their purchasing activities have declined since 2022, but even at the peak the largest (1000+ homes) investors accounted for under three percent of single-family house purchases nationally. Institutional investors matter more in some markets than in others, but in no metro area do companies with 100+ home portfolios own more than five percent of the single-family stock.

As of September 2024, institutional investors owned less than half a percent of single-family housing stock in Minnesota. So, any effect that these investors have on housing prices is likely minuscule and easily outweighed by other market factors.

Indeed, the most comprehensive literature review on this topic, which was conducted by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), shows mixed results. While some studies found that institutional investors raised housing prices in the aftermath of the Great Recession, according to GAO, this could be explained by the “possibility that institutional investors might have been better at choosing neighborhoods with growing housing demand, so home prices might have also risen absent their purchases.”

Explaining further, GAO found no clear evidence that institutional investors lower individual home ownership. This is partly because large corporations tend to buy homes in need of substantial renovations and repair, “the cost of which is out of reach for many homebuyers”. In other words, institutional investors do not always compete with individuals for homes.

For instance, a study quoted by GAO found that

in 2020, two institutional investors reported spending $15,000–$39,000 to renovate each home they newly acquired. In comparison, the study calculated a typical homeowner spends about $6,300 during the first year after purchasing a home.

Corporate investors have been found to lower rents by increasing supply. And by providing rental opportunities to families who otherwise cannot afford homes in desirable neighborhoods, institutional investors have also improved integration and educational opportunities for renters.

What the market needs is more housing

Starter homes, which tend to be more affordable, especially for first-time homebuyers, are effectively illegal to build in large swaths of the country, putting home ownership out of reach for young families. Missing-middle housing, including duplexes and townhomes, is similarly constrained.

As long as demand continues to outpace supply, housing prices will remain elevated. And demand-side fixes, such as those proposed by the Trump Administration, will likely only raise prices further.