As test score results continue to be quiet reminders of the millions of students who fell behind or dropped out entirely during years of disrupted learning, new research out of Stanford University estimates that what began as a temporary setback could snowball into one of the most expensive crises in modern history — a staggering $90 trillion in lost lifetime earnings, productivity, and innovation.

Economist Eric Hanushek paints a stark picture of U.S. student achievement that goes far beyond the disruptions of COVID-19. While pandemic-era learning losses are real, Hanushek shows that the decline in performance on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) began well before 2020 and continued after schools reopened.

In his analysis, Hanushek finds that before COVID average achievement had been falling in math and reading since 2013 and continued declining during and after the pandemic years, despite the federal government putting $190 billion of funding into schools. As overall achievement declined, the disparity between high- and low-achieving students also grew.

These declines translate into serious long-term economic consequences: The average student is projected to lose almost 8 percent of lifetime earnings. (Costs are expected to be substantially higher for the most disadvantaged students because their achievement losses were more pronounced.) Crucially, Hanushek notes that simply returning to pre-COVID achievement levels will only halve the anticipated damage.

Where does Minnesota fall in all of this?

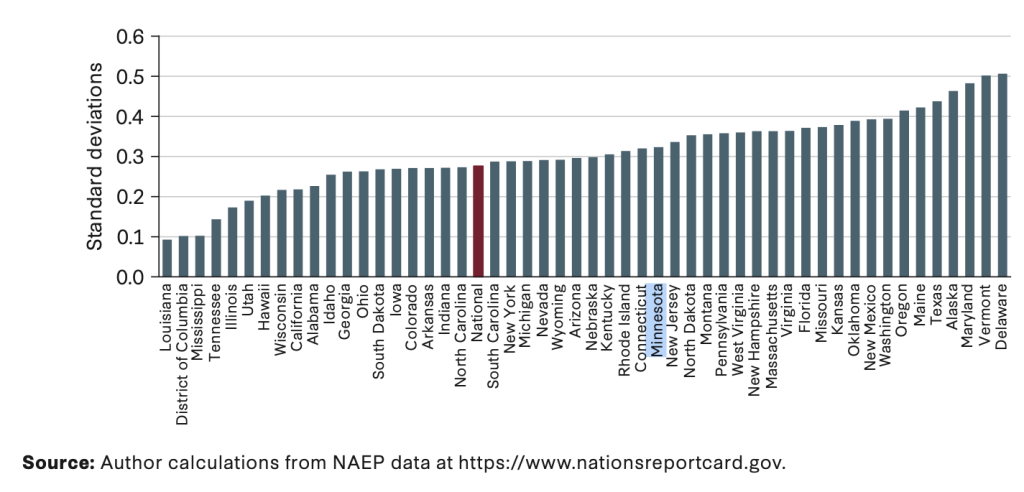

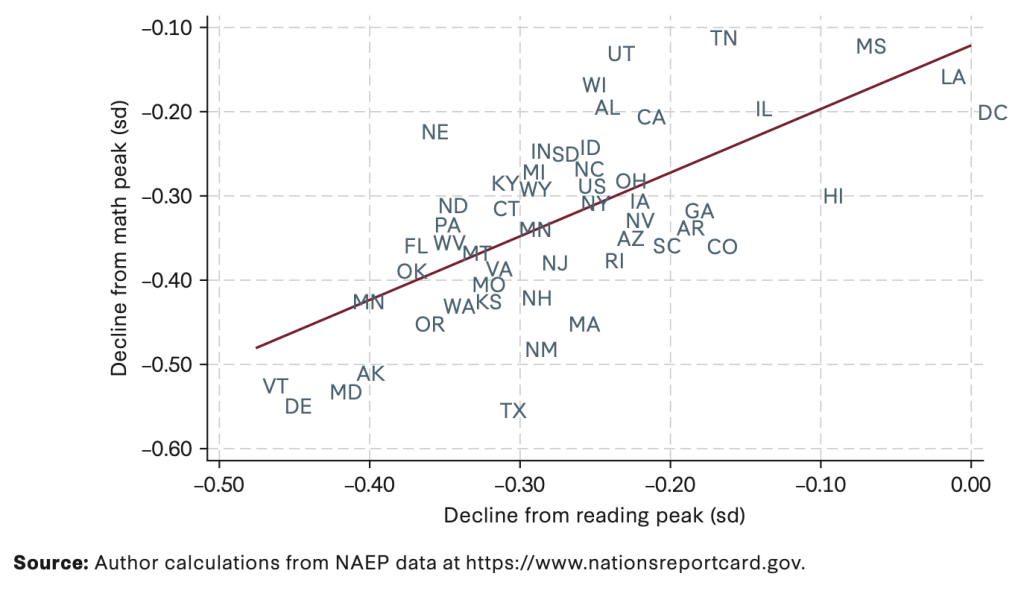

To present patterns of state achievement, Hanushek calculates declines from each state’s peak achievement level. Minnesota’s change in average math and reading performance from its peak is over one-third standard deviations.

Because the significance of standard deviations can be difficult to grasp, Hanushek presents them as economic implications. Lower achievement translates to a lower-skilled workforce and lower earnings, which lead to lower economic growth.

For Minnesota, students can anticipate an average of just under 9 percent or so in lost total expected earnings. Keep in mind that these losses are not a one-off but decreases in lifetime earnings.

Decline in Combined Performance from State Peak

(standard deviations)

Comparison of Total Score Declines in Reading and Math

(standard deviations)

Can we avoid these economic losses?

While student achievement has already fallen — and the economic implications are substantial — Hanushek emphasizes that the learning deficits of current and future students can be addressed before they enter the labor force.

But it is going to take a fundamentally different approach than what has been tried before, Hanushek argues. “Today’s concerns about U.S. educational performance are not new” but persist because reform efforts over the past half century have focused on “retain[ing] the essence of the institutional structure” of the educational system.

While the specifics of each new reform differ, the repeated failure of the broad set of reforms to deal with the achievement challenges of the nation is remarkably consistent and indicates that we need to look at the problem differently. Instead of enhancing the current structure, it is likely time to rethink how we operate our schools.

Perhaps the most critical observation comes from the dynamics of school policy development. Even when there is a successful school policy put into place at scale with validated performance outcomes, there is not a rush by other schools to adopt it.

Hanushek cites the incentive-based personnel changes in Washington, D.C. and Dallas, Texas as one example. Mississippi is another state that has implemented effective large-scale reforms, such as putting literacy coaches in schools, using universal reading screeners, and pairing retention requirements with strong interventions. Alabama’s comprehensive Numeracy Act passed in 2022 requires every K-5 school to have at least one math coach and the use of high-quality instructional materials.

In Hanushek’s view, true remedies to the long-term deterioration of the U.S. education system will require fundamentally reforming it — shifting from incremental add-ons to deep structural change — if we hope to reverse persistent achievement declines and avoid massive future economic losses tied to lower student skills. The United States remains a nation at risk, and time is running out.