You cannot fully understand the Constitution without knowing how the Founders were affected by the saga of ancient Rome.

This post combines all five installments in my Epoch Times series entitled “Ancient Rome and the Constitution.” It is edited for brevity and clarity.

Part I: Rome in Founding-Era Culture

Last year, the Internet resounded with chatter about how much American and British men ponder the subject of ancient Rome. Women started asking their husbands and boyfriends, “Honey, how often do you think about the Roman Empire?”

And based on the responses, American and British men actually think about Rome a lot. Saturday Night Live even produced a very humorous video on the subject.

Still, the interest modern men have in Rome pales compared to that of the American founding generation. By “founding generation,” I mean Americans living between 1763 and 1791—that is, from the time when tension with Great Britain began until the Bill of Rights was ratified. Moreover, members of the founding generation were not only fascinated by Rome, but they also knew a great deal about it.

This new series is about the lessons the Founders drew from Rome when writing and debating the Constitution. I wrote it to help fill a gap left by the modern American public school system.

During the 20th century, public schools stopped requiring the study of Latin, and eventually most removed Latin from their curriculum entirely. They also terminated their courses in civics (although since that time, civics has been making a comeback).

These actions were part of a wider project of downgrading Western civilization. Schools apparently did this to render the curriculum less demanding and to make room for the politically-driven subjects called for by the “diversity” and “multicultural” agenda.

These educational changes largely severed modern Americans from their own traditions. After all, Latin was not only the language of ancient Rome, but for centuries afterward was a principal vehicle for the transmission of learning and culture: Aquinas, Newton, Galileo, Francis Bacon, and many other architects of the modern world wrote some of their greatest works in Latin.

Additionally, courses in Civics had been where students learned the underlying assumptions of the American system of government, its basic components, and how it all worked.

One result from these curricular changes is that today many Americans are ignorant of even the rudiments of Western tradition—including the Constitution: A recent poll found that fewer than half of Americans can name the three branches of the federal government.

Unfortunately, ignorance makes it easier for unscrupulous people to spread misinformation and misunderstanding. But this series, like two earlier ones I authored for the Epoch Times (see here and here), may help readers re-connect with the Constitution, the American Founding, and America’s Founding ideals.

Rome Fascinated the Founders

Have you ever examined the Great Seal of the United States? You can find it on the back of the one-dollar bill.

On the right side of the back is the front of the Great Seal. Its centerpiece is an eagle, which, not coincidentally, was the emblem carried by the Roman legions. The eagle holds a ribbon in his beak. It reads E pluribus unum—“out of many, one.” This Latin phrase is derived from a Roman poem called Moretum: the salad or pesto. In the poem, a farmer uses a variety of ingrediants to make his pesto, fashioning from many foods just one.

When the Confederation Congress approved the Great Seal in 1782, most people believed that the author of Moretum was the Roman poet Virgil (Publius Vergilius Maro, 70 – 19 BCE). Although most scholars now doubt Virgil’s authorship, the point remains that the Founders believed it. Anyway, irrespective of who wrote it, the poem is unquestionably Roman.

On the one-dollar bill’s left side is the Great Seal’s reverse. It contains two other legends, also in Latin. The first is Annuit coeptis. This is an abbreviation of two separate lines in Virgil’s poetry, one from his lengthy agricultural poem the Georgics and one from his epic, the Aeneid. It means that “He [i.e., God] has approved our undertakings.”

The second legend is Novus ordo seclorum, “A new order of the ages.” It comes from Virgil’s Eclogues, his first published book of poetry. The specific source is the fourth or “Messianic” eclogue, about which I’ll say more later in this series.

On either side of the dais of the House of Representatives are other indications of the Founders’ interest in Rome. On the back wall are two fasces —that is, bundled of rods enclosing an axe. Bodyguards protecting high Roman officers carried fasces as symbols of imperium or executive authority. Their further symbolism was strength in unity: Although a single rod can be cracked easily, a bundle is virtually unbreakable.

Rome in Founding-Era education

During the Founding Era, schoolgirls were instructed in “reading, writing, and ‘rithematic,” and then went on to study modern languages, music, household arts, and other useful subjects.

Boys, on the other hand, were immersed in ancient Rome.

Around age eight, after acquiring basic literacy and numeracy, boys began the study of Latin. They read works of history, oratory, drama, poetry, and philosophy. The minority headed for college later began studying Greek. Part of a typical college entrance examination was to take a designated passage from the Greek New Testament and translate it into Latin.

The college curriculum was heavy with the Greco-Roman classics. Students read advanced Latin authors, such as Seneca and Tacitus, and Greek writers like Plato, Aristotle, Xenophon, Polybius, and Plutarch. We shall have more to say about Polybius and Plutarch later.

Colleges supplemented classical studies with theology, modern history, mathematics, geography, science, and other subjects.

Rome in the Wider Culture

The eighteenth century thought of itself as a classical age. Certainly, classical learning had a great influence on the wider culture. As just mentioned, Latin was dominant in the grammar school curriculum. Although only a small fraction of boys attended college, the college-educated exercised an outsized influence. One reason was the popularity of almanacs, which were disproportionately written and published by the college-educated. Another was that college-educated men often were elected to public office. For example, 27 of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence had at least some college education, as did 23 of the 39 signers of the Constitution.

Men and women who never attended college but aspired to an education often undertook to study the Greco-Roman classics. Patrick Henry, to name one, did not attend college. But his father introduced him to the Roman historian Livy. For the rest of his life, Henry annually re-read Livy in English. Benjamin Franklin had very little formal education, but taught himself Latin and became conversant with Roman history.

In 1767 and 1768, John Dickinson of Delaware and Pennsylvania (later one of the Constitution’s most influential drafters and promoters) penned a series of newspaper op-eds entitled Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania. They outlined the colonial case against Great Britain. Americans loved them, and Dickinson became, after Franklin, America’s first national celebrity. In his Letters, Dickinson included quotations—attributed and unattributed—from Romans like Cicero, Sallust, Tacitus, and Virgil, and from Greeks such as Demosthenes and Plutarch.

No one seems to have thought it the least bit odd to cite such authors in op-eds directed at the general public.

Part II: Roman History and Founding-Era Faves

The Sweep of Roman History

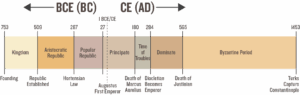

The Roman state, together with its Byzantine successor, existed for about two thousand years. According to tradition, Rome was founded in 753 BCE as a small city-state, ruled by a king with the assistance of a senate or council of elders. In 509 BCE, a revolution overthrew the monarchy and established an aristocratic republic. The king was replaced with two annually-elected executives, initially called praetors (leaders) but eventually renamed as consuls. The praetors continued as judicial officers.

Romans showed an aptitude for war, and gradually absorbed other peoples, either by conquest or alliance. By the year 287 BCE, Rome had become the dominant power in Italy. However, the fact that all male citizens were subject to military service had domestic consequences: Men who served in war had a claim to a say in government. That year witnessed adoption of the Hortensian Law. It allowed an assembly composed only of the common people (the plebians) to enact laws without regard to the wishes of the aristocracy.

Still, the aristocracy remained powerful, and Rome never became a constitutional democracy in the modern sense.

Over the ensuing century and a half, Rome waged three successful wars with the north African state of Carthage and four with Macedonia, enabling it to extend its influence around the Mediterranean. This expansion also had domestic consequences: It created severe strains in the Roman republican constitution and gave more power to military commanders. After a series of civil wars and several dictatorships (including the dictatorship of Julius Caesar), the constitution underwent a fundamental change. Caesar’s grandnephew and heir, Octavian, became the most influential man in the state. He assumed the name Augustus (“revered”) and is considered the first Roman emperor. Historians commonly designate his reign as extending from 27 BCE to 14 CE. Thus, as the New Testament reports, Augustus was emperor when Jesus of Nazareth was born.

For over 160 years following the death of Augustus, republican institutions continued to exist side-by-side with the imperial authority. The Senate continued to meet—and in some ways expanded its power. Consuls and other magistrates were still elected, either by the popular assemblies or by the Senate. In theory, the emperor was merely the first citizen or princeps. For this reason, historians call the period from the ascension of Augustus until the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180 CE the principate. It was during this period that the Roman Empire was most prosperous and reached its greatest extent.

The century following the principate, however, was a very unsettled time. The empire almost collapsed under the challenges of civil war, plague, and foreign invasion. The emperors became mere military dictators, and most of them died in war or from assassination. Fortunately, near the end of the period a series of hardworking and capable emperors managed to stabilize the situation. The last of these was Diocletian, who assumed office in 284. He reorganized the empire into an oriental-style despotism, but with separate emperors in the east and west. Thus began the period known as the Dominate—a word reflecting the emperor’s status as absolute dominus or lord.

The stability of authoritarian government came at the cost of freedom, prosperity, and strength. Many citizens fled the empire for freer lands to the north and east. At the same time, military pressure from the north and east caused the weakened empire to lose large swaths of territory, particularly in the west. In 476, Rome and Italy came under Germanic (“barbarian”) rule.

However, emperors continued to reign from the eastern capital at Constantinople (modern Istanbul), and one of them—Justinian (reigned: 527-565)—even recaptured Italy and some other western provinces. After Justinian’s death, however, the eastern empire gradually became little more than a large Greek state. Historians call it the Byzantine Empire, and it lived on until 1453.

This video illustrates expansion and contraction of Roman and Byzantine territory over time. This timeline summarizes the full sweep of Roman history:

Founding-Era Favorites

The American founding generation showed little interest in Roman history before the republic or after the early principate. All of their favorite writers lived between 200 BCE and 120 CE, and the stories they told were of that period and of the old Roman republic. Among the authors read by the American Founders, six stand out as particularly influential on the Constitution: Polybius, Cicero, Virgil, Livy, Tacitus, and Plutarch.

Polybius

Polybius (c.200 BCE – c. 118 BCE) was a Greek who became famous writing about Rome. He was born in Megalopolis, in southern Greece. Polybius’ father was on the town council, and when Polybius was about 30, he was elected as a councilor as well. At the time, the Greek states were still independent. Rome—anxious to assure that they did not ally themselves with its enemies—demanded that Greece send hostages to Italy. Polybius was among those sent.

The hostages were treated well and allowed considerable freedom of movement. Polybius impressed leading Romans and became the mentor of the patrician Scipio Aemilianus—the man who eventually would destroy Carthage. Scipio was enthusiastic about learning, and through him Polybius became acquainted with some of Rome’s best scholars. Eventually, he became a Roman citizen and a magistrate, and led diplomatic delegates and a voyage of discovery down the western coast of Africa.

Polybius wrote a history of Rome for his fellow Greeks to explain why the republic had been so successful. That history proved to be influential on the American Founders’ constitutional thinking.

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 BCE – 43 BCE) was born in Arpinum (now Arpino), in Italy, about 50 miles southeast of Rome. His father sent him to Rome to be educated, and he made his mark through the sheer force of his personality, his ability as a lawyer, and the power of his oratory. After election to several lesser offices, he served as consul (63 BCE). While in that position, Cicero suppressed a dangerous rebellion led by one Lucius Sergius Catilina (whom English speakers call “Catiline”).

Cicero’s greatest contribution came later: He wrote a series of essays and dialogues synthesizing Greek ideas (and his own) for a Latin audience. During the centuries between the collapse of the empire in Europe and the modern era, Cicero’s writings were central to the educational canon. His views of government and civic obligation were immensely influential on the American Founders.

Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (Virgil) (70 BCE – 9 BCE)—whom we call Virgil or Vergil—was yet another product of a family prominent only locally. He was born in a small place called Andes, near Mantua, in northern Italy. He did not pursue a political, legal, or military career, but decided to write poetry. After some youthful efforts—of which the Moretum (mentioned in our first installment) may be one example— he published the Eclogues, a series of ten pastoral poems averaging about 83 lines each. The Eclogues made Virgil famous. He followed with his long agricultural poem, the Georgics, and with a grand epic on Roman origins, the Aeneid.

The American Founders frequently quoted other Roman poets. But as the Great Seal of the United States testifies, Virgil was their favorite. During the constitutional debates of 1786-1791, he was quoted so often he became the de facto Poet Laureate of the American Founding.

Livy

Titus Livius (64 or 59 BCE – 19 CE) lived through the last years of the Roman republic and throughout the reign of Augustus. He was born in Patavia—modern Padua—in northeastern Italy, just west of Venice. Like all the other authors examined here, Livy’s family was, at most, only locally prominent. Like Virgil, he chose not to pursue a civic career, instead electing to write history. His vivid portrayals of republican heroes, exemplifying Roman courage and virtue, appealed enormously to the Founders.

Tacitus

Cornelius Tacitus (56 CE- c. 120) lived during the height of the Roman Empire. He was born into a family so obscure that we do not know his birthplace—although some speculate it was in northern Italy or Gaul (France). As a boy, however, Tacitus showed promise, and was educated in Rome. Like Alexander Hamilton, he compensated somewhat for his modest origins by marrying into a leading family.

Tacitus rose through the ranks of civil office, becoming consul for part of the year 97. He later served as governor of one of Rome’s most important provinces.

Scholars rate Tacitus as perhaps the greatest of all Roman historians. He focused on the history of the Empire during the eighty years after the death of Augustus. His was largely a tale of misrule and corruption. Eighteenth-century Americans who found Livy’s history to be rich in positive examples found Tacitus’s account to teem with sobering but useful negative examples.

Plutarch

Plutarch (46 – after 119) was, like Polybius, a Greek who wrote about Rome. He was born in Chaeronea, a small village in Greece. His father was a biographer and philosopher, and Plutarch studied in Athens, then a university town. On trips to Rome, he befriended influential people, including, perhaps, the Emperors Trajan (reigned 98-117) and Hadrian (117-138). But he always returned to Chaeronea, where he lived and operated a school.

The American founding generation admired Plutarch’s essays on morals, but it was his biographies of great Greeks and Romans that captured their imagination.

Note a common fact about these six authors: All rose to fame and influence from modest origins—testimony to the upward mobility of Roman society during the popular republic and the principate.

Part III: The Constitution’s Adoption and Moral Lessons the Founders Learned from the Romans

The Constitution’s Adoption

In 1786, the delegates at a convention of states meeting in Annapolis, Maryland, recommended to their home states that they call a wider convention for the following May in Philadelphia to

“take into consideration the situation of the United States, to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union . . . .”

The surrounding history makes it clear that the delegates used the word “constitution” to refer to the entire political system (as the word was used in the Declaration of Independence), not merely to the Articles of Confederation. In December, 1786, Virginia—one of the states represented at Annapolis—issued the formal convention call for Philadelphia. All the other states except Rhode Island agreed to participate, although the Confederation Congress, Massachusetts, and New York tried unsuccessfully to limit the agenda to amending the Articles.

The convention proceedings continued from May 25 through September 17, 1787. Despite frequent modern comments about the “long hot summer,” in fact the summer of 1787 was a relatively cool one.

On the last day of the proceedings, the convention sent its proposed Constitution to Congress, which unanimously transmitted it to the states. Eventually, elected conventions in all thirteen states ratified it, culminating in approval by Rhode Island on May 29, 1790. The Republic of Vermont ratified in January, 1791 and became the fourteenth state.

The new Federal Congress met in 1789 and, pursuant to a “gentlemen’s agreement” by which the Constitution was ratified, proposed twelve amendments as a new Bill of Rights. By the end of 1791, the requisite number of states had approved ten of them.

When these essays refer to “the constitutional debates,” they mean the public debates over the entire period of 1786 through 1791. They included discussions leading up to the Constitutional Convention (1786-1787), the Convention itself (1787), the ratification debates (1787-90), and the proceedings in 1791.

Lessons in General

Lessons from ancient Rome impacted the constitutional debates at every stage. They included lessons in morality, constitutional history, and rhetoric.

A disproportionate share of these lessons derived from the six classical authors discussed in the second installment: Polybius, Cicero, Virgil, Livy, Tacitus, and Plutarch. But some participants in the debates learned them from intermediate sources rather than reading those authors directly. For example, Baron Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws was one of the most quoted works during the constitutional debates. But Montesquieu’s book relied very heavily on Roman authors.

Moral Lessons

Although both Roman and modern authors frequently have depicted Romans as morally depraved, with some exceptions (gladiatorial contests, for example) basic moral standards were not that different from those prevailing in America before 1960.

Romans, like the authors of the Bible, often interpreted history from a moral point of view. The American Founders drew inspiration from the heroism depicted by Livy, accepted instruction from the Moralia (moral essays) written by Plutarch, and shuddered in revulsion at the depravity described by Tacitus.

Livy told of republican virtue: How people facing oppression, danger, and other challenges persevered and overcame. But he also related how, during times of crisis, the two consuls could be paralyzed by their differences, forcing the Senate to grant a six-month appointment to a single “dictator.”

Livy related the story of Lucius Quinctus Cincinnatus: How he came out of retirement to save Rome from the hostile armies surrounding the city. How he accepted the office of dictator, rallied his country’s troops, defeated the enemy, and then laid down his power—all in a period of sixteen days.

Livy also related how the general Quintus Fabius had frustrated Hannibal by avoiding pitched battles (which Hannibal always won) and adopting guerrilla tactics instead.

Tacitus, by contrast, told of the moral depravity of emperors selected for their family connections and remaining in office for life.

In statues and in other ways, members of the founding generation portrayed George Washington as “the American Cincinnatus”—because he left his plow to save his country, and then returned to his plow—and as “the American Fabius,” because he won the Revolutionary War largely by tactics of avoidance and delay.

Washington, however, did not model himself on either Cincinnatus or Fabius, preferring yet another Roman moral hero: Cato the Younger.

The moral lessons taught by Roman authors help explain the sentiment expressed by some Founders to the effect that a republican government can survive only as long as the people remain virtuous. Despite that sentiment, though, the Founders shaped the Constitution to account for the fact that people often are not virtuous.

Roman Moral Examples in the Ratification Debates

During the debates over whether to ratify the Constitution, participants on both sides—the pro-Constitution “Federalists” and the anti-Constitution “Antifederalists”—often called on Roman moral illustrations to underscore their messages. Cicero was viewed as the archetype of the wise and good statesman, who showed wisdom and courage in suppressing the evil insurrectionary Catiline. Accordingly, a Pennsylvania Antifederalist writing under the pseudonym “Cicero” announced he would respond to a Federalist “Catiline.” And a Massachusetts Federalist branded an anonymous opponent as a “MODERN CATILINE.”

Participants, particularly Antifederalists, employed the writings of Tacitus to demonstrate the risks of power and corruption. Thus, a Virginia Antifederalist writing as “Brutus” recounted abuses by the Emperors Tiberius and Nero. A Rhode Island Antifederalist writing as “Cato junior,” relied on Tacitus to show that corrupt governments endeavor to corrupt the people:

“Ill governments, subsisting by vice and rapine, are jealous of private virtue, and enemies to private property . . . . Hence it is, that to drain, worry, and debauch their subjects, are the steady maxims of their politics, their favourite arts of reigning. In this wretched situation the people to be safe, must be poor and lewd . . . .”

“Cato junior” added that the contagion is mutual. A corrupted people idolize corrupt leaders:

“Even Nero (that royal monster in man’s shape) was adored by the common herd at Rome …. Tacitus tells us, that those sort of people long lamented him ….”

Can you think of modern American political leaders who have sought to retain power by corrupting the people?

Part IV: Historical and Constitutional Lessons the Founders Learned from the Romans

General Principles and Mixed Government

Before getting into the details of writing a constitution, Americans had to consider their goals. This entailed identifying the basic principles the constitution would reflect. John Adams was serving as a diplomat in Europe during most of the constitutional debates. While there, he wrote an encyclopedia of republican governments: A Defence of the Constitutions of the United States. (The “Constitutions” referred to were those then in force in the states.) The first volume was issued in early 1787 and was cited frequently during the constitutional debates.

In that volume, Adams relied on Cicero for some basic political propositions, including the following:

- Law is built on justice; where there is no justice, there is no law.

- A nation is not just a mass of individuals, but an association based on consent.

- The best constitution mixes elements of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy.

- Unmixed governments degenerate into corrupt forms, particularly into tyranny. A tyranny is not a true republic because a republic is the property of the people, while in a tyranny everything belongs to the ruler.

The points about mixed and unmixed government were particularly important to the constitution-makers. Aristotle had divided uncorrupted constitutions into monarchies, aristocracies, and democracies. But he observed that each uncorrupted form tends to deteriorate into a corresponding corrupt form. Monarchies degenerate into tyrannies, aristocracies into oligarchies, and democracies into mob rule.

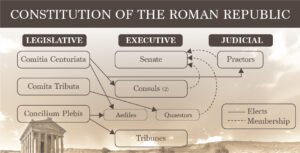

When explaining the Roman republic’s success to his fellow Greeks, Polybius emphasized Rome’s unwritten constitution as a major contributor to that success. He pointed out that its government was neither a monarchy, aristocracy, or democracy, but a mixture of all three: The republic’s popular assemblies were (somewhat, but not entirely) democratic, the Senate was (somewhat, but not entirely) aristocratic, and the consuls shared the power formerly exercised by kings. Each element checked the other, preventing degeneration into corrupt forms.

The following chart depicts a simplified version of the government of the Roman republic. It shows three of the four popular assemblies, omitting one that served purely religious purposes. The chart suggests how the different branches checked each other.

Note that under the republic, the Senate was primarily an executive rather than a legislative body. During the early empire, it took on more legislative functions.

Federalism

The Constitution’s greatest contribution to political theory may have been its system of federalism, under which the people divided sovereignty, granting some to the central government and the rest to the states. While developing this concept, the Founders consulted a number of federal models, including confederacies of city- states in ancient Greece and more recent confederacies in Switzerland and the Netherlands. The Founders also took into account the British empire’s working arrangement before 1763, in which the central government in London controlled foreign affairs, the post office, and commerce with foreign nations and among units of the empire, while the colonies otherwise governed themselves.

Among these models, the pre-1763 colonial arrangement probably was the most influential among the Founders. However, they also considered seriously the Greek confederacies. Their information on those confederacies derived primarily from Polybius and Plutarch.

Polybius and Plutarch were the source of John Adams’ discussion of Greek confederacies in his treatise on republican governments. They likewise were sources for James Madison’s famous pre-convention research notes, Of Ancient and Modern Confederacies. Madison deployed his knowledge of the subject in Federalist No. 18, where he compared the Greek Amphictyonic Council to the United States under the Articles of Confederation:

“The powers [of the Council], like those of the present Congress, were administered by deputies appointed wholly by the cities in their political capacities; and exercised over them in the same capacities. Hence the weakness, the disorders, and finally the destruction of the confederacy. The more powerful members, instead of being kept in awe and subordination, tyrannized successively over all the rest . . . .”

Madison concluded that the new federal government should act primarily on individuals, not on the states. By contrast, Madison’s then-rival James Monroe—the future president, but at the time an Antifederalist—relied on Polybius’ account of the Greek Achaean League to argue that the Articles of Confederation, if amended somewhat, would be adequate for American needs.

Another lesson drawn from Polybius and Plutarch was that if a confederation has some members that are monarchies and others that are republics, the monarchies will try to undermine the republics. This lesson led to the Constitution’s Guarantee Clause (Article IV, Section 4), by which the United States guarantees to every state a republican form of government.

In Federalist No. 34, Alexander Hamilton drew on his knowledge of the Roman constitution to answer opponents’ claims that sovereignty could not be divided:

“To argue . . . that this co-ordinate authority cannot exist, is to set up supposition and theory against fact and reality. . . . It is well known that in the Roman republic the legislative authority, in the last resort, resided for ages in two [actually four!-ed.] different political bodies not as branches of the same legislature, but as distinct and independent legislatures . . . It will be readily understood that I allude to the COMITIA CENTURIATA and the COMITIA TRIBUTA . . . [T]hese two legislatures coexisted for ages, and the Roman republic attained to the utmost height of human greatness.”

Other Constitutional Lessons

During the course of the constitutional debates, participants looked to Roman sources for other lessons as well. Thus, a Virginia Federalist cited Cicero in support of the Constitution’s grant of the pardon power to the president and its bans on state and federal ex post facto laws (retroactive criminal laws).

In Federalist No. 63, Madison used the Roman example to underscore the need for a federal Senate. “[H]istory informs us,” he wrote, “of no long-lived republic which had not a senate.” And Hamilton, writing in Federalist No. 70, emphasized the need for a single President rather than an executive council or other plural executive:

“Every man the least conversant in Roman history, knows how often that republic was obliged to take refuge in the absolute power of a single man, under the formidable title of Dictator. . . . A feeble Executive implies a feeble execution of the government. A feeble execution is but another phrase for a bad execution; and a government ill executed, whatever it may be in theory, must be, in practice, a bad government.”

On the other hand, an opponent, writing under the name of “Caveto” (Latin for “Be ye warned!”) cited Tacitus’s Histories on the Risks of a Unitary Executive:

“They who would put their country under such a form of government, and think thereby to render its condition more safe and easy, must suppose that none but good Princes shall be upon the throne, which did not happen to the Romans, when they had the choosing of their own masters—They were often mistaken in their choice; some had good inclinations, but were corrupted by those about them. In others, the seeds of vice and cruelty lay undiscovered as in Tiberius [the emperor immediately succeeding Augustus]; others’ nature had formed well enough, but so much power turned their heads, and made them worse—Solusque Vespasianus Omnium ante se Principum in melius mutatus est.” (Compared to all the emperors before him, only Vespasian turned out for the better.”)

Part V: Lessons in Language the Founders Learned from the Romans

The Value of Rhetoric

Because Latin was such an important part of the eighteenth-century educational curriculum, many of the leading Founders were bilingual. Because so many educated people understood at least some Latin, speakers resorting to Latin words and phrases could be assured that their messages were received.

This bilingual and cultural knowledge provided an enormous vocabulary and a massive store of literary references. As a result, educated members of the founding generation were highly adept in expressing their ideas and sentiments.

Understanding how Founding-Era speakers employed Roman history and Latin expressions can be useful for grasping the purpose and scope of constitutional clauses. By way of illustration, an Antifederalist writing under the name “A Farmer” quoted lines from the poem known as Virgil’s third eclogue to compare the collection of direct taxes to over-milking female sheep. As explained below, this comparison helps us understand the definition of the Constitution’s phrase “direct Taxes.”

Another incident involved the Constitution’s impeachment-and-removal procedure for federal officers. The framers adopted a compromise between those who favored impeachment-and-removal for almost any reason and those who either wanted no impeachment procedure at all or one that was severely limited. When the Antifederalist framer George Mason stated that the Constitution’s method for impeaching the President “brings to my recollection the remarkable trial of Milo at Rome,” he was telling his audience that the document’s impeachment-and-removal provisions were defective. His point was that even after being impeached, the President—before and during trial in the Senate—would still be commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and might use those armed forces to intimidate the Senate into acquitting him.

On the other hand, popular acceptance of the Constitution suggests (although it does not prove) that most people did not think this was a significant risk and that the framers’ impeachment-and-removal compromise was adequate.

Plutarch and Pseudonyms

After the Constitution was drafted and proposed, the in-state debates over ratification ensued. Participants in the ratification debates, like participants earlier in the constitutional process, relied on Polybius, Cicero, Virgil, Livy, Tacitus, Plutarch, and other authors. But they utilized Plutarch, Cicero, and Virgil most of all.

The fourth installment of this series discussed the influence on the framers of Plutarch’s reports on Greek confederations. During the ratification era, his influence was felt more in how disputants used his biographies of famous Greeks and Romans. To explain this, however, some background is necessary:

Modern writers on the Constitution—including, alas, the Supreme Court—regularly confuse the First Amendment’s protection of freedom of speech with its protection of freedom of the press. In the Founders’ view, they were different. “Speech” was in-person discourse. “The press” was communication through a medium, such as a newspaper, pamphlet, or poster. “Speech” once uttered disappeared into air. “The press” preserved communication in permanent form. “Speech” was local. “The press” could be world-wide. In the course of “speech,” the audience knew, or easily could find out, the identity of the speaker. When communication was via “the press,” the identity of the author usually was hidden.

For these reasons, the rules limiting freedom of speech were different from those limiting freedom of the press. Moreover, the right to remain anonymous, except in cases of defamation or crime, was absolutely central to freedom of the press. Most participants in the ratification debates who used “the press” hid their identity with pen names. They wanted their arguments assessed on their merits, rather than dismissed or accepted because of who they were.

Writers in the ratification debates commonly used characters in Plutarch’s biographies as pen names. Among the principal subjects of Plutarch’s biographies, about 40 percent were employed as pseudonyms. Authors identified themselves as “Brutus,” “Caesar,” “Camillus,” “Cato,” “Cicero,” and “Fabius,” among many others.

Sometimes the author selected his or her pen name to send a message. A populist writer might adopt the name “Publicola” to indicate that he was a “friend of the people.” A person seeking to communicate rustic values might call himself “Agricola” (farmer). Several called themselves “Brutus” to indicate dedication to republican values, because the Brutus who assassinated Caesar purportedly did it to preserve the republic, which five centuries earlier an ancestor also named Brutus had helped to establish.

Cicero

Cicero’s fervid oratory provided a rich supply of expressions for communicating ideas and emotions. Consider an essay by an anonymous New York Antifederalist. His argument was that the Constitution’s advocates were trying to rush Americans into approving a defective document. He could have written it that way, but it was much more effective to compare Federalist pressure to Cicero’s description of Rome during Catiline’s conspiracy:

“There is treachery within, danger within, an enemy within; we must fight against dissipation, insanity, and crime!”

(Original: Intus insidiae sunt, intus inclusum periculum est, intus est hostis. Cum luxuria nobis, cum amentia, cum scelere certandum est!

On the other hand, a supporter of the Constitution, North Carolina’s James Iredell (later a Supreme Court justice), argued that the Constitution embodied another saying by Cicero: Salus populi suprema lex esto. “The safety of the people shall be the supreme law.”

Virgil

The poetry of Virgil was an even more powerful vehicle for communicating ideas and emotions than the oratory of Cicero. Here are some illustrations:

Antifederalists who believed the Constitution’s supporters were railroading the public quoted the lines from the Aeneid describing how the trusting Trojans dragged the infamous and fateful wooden horse into their city:

Instamus tamen immemores caecique furore

et monstrum infelix sacrata sistimus arce.

“Yet we push forward, unmindful, blinded by madness,

and erect the ill-omened monstrosity within our sacred citadel.”

The Virginia Antifederalist George Mason believed adoption of the Constitution could lead to the dispossession of thousands of Virginia farmers. He drove home his point by paraphrasing the lament of a dispossessed farmer Virgil’s first eclogue: Nos patriae fines et dulcia linquimus arva—“We leave the bounds of our homeland, we leave our sweet fields.”

As mentioned earlier, an author writing as “A Farmer” quoted Virgil’s third eclogue to warn that the Constitution would permit Congress to levy direct taxes. In doing so, Congress would act like the unscrupulous custodian of sheep entrusted to his care:

hic alienus ovis custos bis mulget in hora,

et sucus pecori et lac subducitur agnis.

“This custodian milks sheep that don’t belong to him twice an hour;

Thus, the juice of the ewe is taken stealthily from the lambs.”

As noted earlier, this quotation is useful for interpreting the Constitution’s phrase “direct Taxes.” Again, some background is necessary:

For many years, apologists for federal power have tried to circumvent the Constitution’s restrictions on direct taxes by arguing that only head taxes and real estate levies are direct—that all other taxes are indirect, and therefore free from the Constitution’s restrictions. But the quoted lines suggest that direct taxes may burden milk (i.e., the products of property) as well as sheep (the property itself). In other words, direct taxes include income as well as property levies. My own research has shown that this is definitely the case.

Another example—this one from advocates of the Constitution:

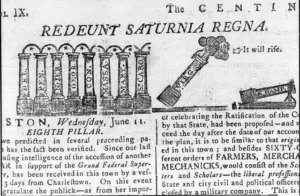

Virgil’s fourth eclogue was particularly famous for its prediction that the birth of a special child would usher in a new “reign of Saturn”—that is, a new Golden Age. This poem is called the Messianic Eclogue, and for centuries Christians identified it with the birth of Jesus of Nazareth.

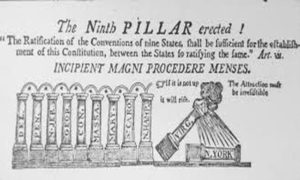

While the Constitution’s ratification was pending, some Federalist newspapers in Massachusetts printed cartoons depicting thirteen columns representing the thirteen states. As each state ratified the Constitution, its column rose from a prostrate to a vertical position, producing a growing colonnade. The Massachusetts Centinel celebrated the predicted ratification by Virginia with a cartoon showing vertical columns for the eight states that already had approved the Constitution together with Virginia’s column in a 45-degree position. Above the columns was the fourth eclogue’s phrase, REDEUNT SATURNIA REGNA—“the reign of Saturn (i.e., the Golden Age) returns.”

However, as it turned out, New Hampshire ratified before Virginia. Shortly thereafter, the Boston Independent Chronicle commemorated New Hampshire’s adherence to the Union with a similar cartoon. It showed nine vertical columns, with Virginia’s column in the 45-degree position, and New York’s still lying flat. The legend over this cartoon was another line from the fourth eclogue: INCIPIENT MAGNI PROCEDERE MENSES!—“The great months (i.e., the new era) will now begin!”

Conclusion

The Founders were fascinated with the history of Ancient Rome and educated in Roman language, history, and literature. In writing and adopting the Constitution, they drew many lessons from the Roman experience—lessons in morality, constitutional history, and rhetoric.

Understanding how they resorted to ancient Rome is central to a deeper understanding of the Constitution itself.