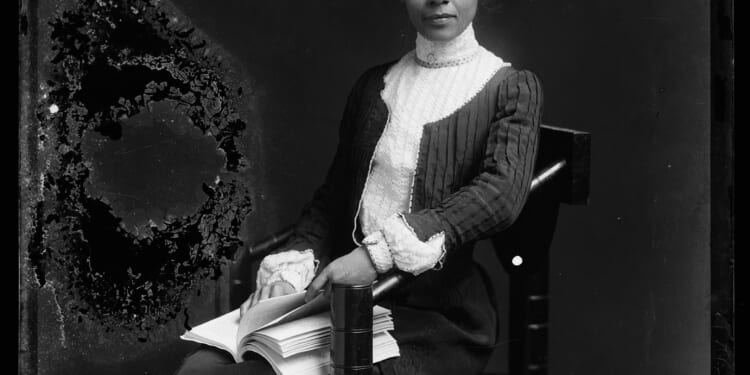

Public education is a hard-fought American right, and one that hasn’t always existed. Throughout American history, some have been unable to achieve a formal education due to the limits of geography, community organization, or time. Others have been kept from it. After the Civil War ended, thousands of teachers, many from the Black community, began the hard work of transforming the lives, hearts, and minds of formerly enslaved people through education. The Reconstruction period was difficult and rife with dissent. But many spent their lives in the service of others, to their benefit and to this country’s great benefit. One of those people was Anna Julia Cooper.

Cooper’s life

Cooper was born in North Carolina, the enslaved child of an enslaved woman and her white master. Just after her family’s emancipation, at ten years old, Cooper entered the St. Augustine Normal School and Collegiate Institute, a school for newly freed slaves rooted in the classical tradition, supported by the Freedmen’s Bureau and other religious institutions.

Cooper received a scholarship to attend St. Augustine and, due to the shortage of teachers, began to work as a teacher’s aide at the school as a condition of her scholarship, as was typical practice at the time. She spent fourteen years at the school, taking the more rigorous men’s courses, moving upwards from pupil to teacher. Here, she developed a deep desire to help her community and a heart that desired justice.

After her two-year marriage to an Episcopalian minister ended in his death from disease, Cooper began to attend Oberlin College, a school rooted in the abolitionist movement, at the age of 21. Oberlin was one of the first colleges to open its doors to both Black people and women. Cooper successfully petitioned to take the Gentleman’s Course of study, a four-year bachelor’s degree that included a focused study on the classics. During her time at Oberlin, she lived with a white professor and his family and tutored white students. Cooper learned how to create a social life with both the Black and White communities at Oberlin and hone her writing to fairly address the rifts between them.

She then taught at Wilberforce University, the first HBCU in the nation, which aimed to provide a classical education for Black people. In 1887, she found herself teaching in Washington, D.C. at the Washington Colored High School, the first public school in the nation for Black students. The school emphasized the education of the whole person, and gave students both a classical curriculum and extracurricular experiences like nature studies. Every student learned Latin, and could learn other languages like French, German, and Spanish. She rose to the principal’s office, and her students obtained recognition for being able to pass the entrance exams of Ivy League schools.

Cooper briefly lost her job at the high school after a conflict with a white superintendent, who wanted to change the curriculum to a trade school format that Cooper believed was a disservice to the minds of Black students. Eventually, she was asked to return — and her commitment to her community was so strong that she did.

Her accolades increased. She began her doctorate’s degree at Columbia, and completed it in France at Sarbonne. Cooper was the fourth African-American woman ever to earn a doctorate. After 1930, she served as president of Frelinghuysen University. She worked tirelessly, taking in six young orphaned relatives and allowing her home to serve as overflow classroom space. She advocated for the Black community throughout her entire life, which spanned from Reconstruction to 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education. Cooper, interestingly, was against the court’s ruling, believing that the historic wrong was not being righted properly. She felt that Black children would not be given a rich classical education that could provide them with cultural literacy if they were forced into desegregated classrooms with racist, vindictive white teachers. Her perspective on this case shows her commitment to excellence and rigor for the education of the Black students under her care.

Anna Julia Cooper, a former slave, performed the slow, hard work of education for her whole life, serving as a teacher, principal, and university president until her death in 1964. While Cooper’s life is fascinating, her true worth as a public figure comes from her writings.

Cooper’s ideas

Cooper taught at a time when the fate of education for Black students (and, to some extent, White students) was under great contention. Booker T. Washington founded Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute to provide industry-focused self sufficiency for uneducated former slaves, while W.E.B. Du Bois argued that a life spent in Greek and Latin should be the essential priority for Black men and women. Scholar Dr. Anika Prather argues in the book The Black Intellectual Tradition: Reading Freedom in Classical Literature that Cooper paved a mediating media via. Dr. Prather points to Cooper’s tripartite formulation of a quality education in her 1930 essay On Education, where she writes

So long as the wretchedest hovel may culture germs of disease and misery against which the proudest palace is not immune, the submerged tenth take on a terrible significance in the building up of men, and the only salvation lies in leaving the ninety and nine in the wilderness and going after that which is lost. The only sane education, therefore, is that which conserves the very lowest stratum, the best and most economical is that which gives to each individual, according to his capacity, that traning of “head, hand, and heart,” or, more literally, of mind, body and spirit which converts him into a beneficent force in the service of the world.

In other words, education must include both classical, spiritual, and practical training, because the purpose of education is to shape the entirety of the student.

Cooper argued that academic training and a grounding in the classical tradition was essential for all Black students, even those that would spend their lives in physical labor.

Brain power insures hand power, and thought training produces industrial efficiency…Enlightened industrialism does not mean that the body who plows cotton must study nothing but cotton and that he who would drive a mule successfully should have contact only with mules. Indeed it has been well said “if I knew my son would drive a mule all his days, I should still give him the groundwork of a general education in his youth that would place the greatest possible distance between him and the mule.”

Cooper thus dignifies physical work and centers manual labor on the man performing the labor — seeing him as a thoughtful, creative being whose work does not degrade or define him.

Deeply desirous that Black students would become immersed in what she viewed as a liberating Classical tradition, Cooper argued that all students, no matter their social status, should receive a rigorous education that could impart a strong culture into their broken community. In On Education, she finished with an impassioned plea that society think carefully about how children are educated.

[T]he industries and ideals of a nation cannot but be enriched by the sound of intelligence of all the people derived from thorough general education in its schools.

Any scheme of education should have regard to the whole man—not a special class or race of men, but man as the paragon of creation, possessing in childhood and in youth almost infinite possibilities for physical, moral and mental development. If a child seem poor in inheritance, poor in environment, poor in personal endowment, by so much the more must organized society bring to that child the good tidings of social salvation through the schools.

Cooper was deeply concerned with the plight of Black women in particular. She had, after all, been forced to petition at two institutions to take the more rigorous men’s courses. Cooper argued that Black women possessed a special power to serve their people and all of humanity in her book A Voice From the South. This passage has been often quoted and has earned her a title as a Black feminist.

Only the BLACK WOMAN can say “when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole Negro race enters with me.” Is it not evident then that as individual workers for this race we must address ourselves with no half-hearted zeal to this feature of our mission? The need is felt and must be recognized by all. There is a call for workers, for missionaries, for men and women with the double consecration of a fundamental love of humanity and a desire for its melioration through the Gospel; but superadded to this we demand an intelligent and sympathetic comprehension of the interests and special needs of the Negro.

Dr. Prather argues that this passage is best primarily understood within Cooper’s love for humanity. The deeply personal perspective is rooted in Cooper’s identity as a Black woman, and “as she writes…she extends the invitation to all people to rise to the call of the mission to serve humanity in some way.” (Reading Freedom in Classical Literature, 200)

While Cooper’s words are bound by time and space, the truth of her words penetrate throughout history, just like the Classical texts she spent her life sharing. She emphasized an education that taught the head, hand, and heart. She saw her life as an education as a missionary work, and believed that a humanitarian commitment required a society willing to give their time in service. Even though the Classical tradition is today sometimes denigrated as empty words spilled from a rotting ivory tower, she believed, along with black luminaries such as W.E.B Du Bois, Fredrick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., and Toni Morrison, that it was full of universal truths that acted as powerful liberation agents. These convictions can be upheld today as we educate children of all colors.

Cooper did not believe that some people were worth more than others, but she did say that some types of people were more in need than others: those who can serve. These servants are still in need today. She wrote in A Voice From the South that

We need men and women who do not exhaust their genius splitting hairs on aristocratic distinctions and thanking God they are not as others ; but earnest, unselfish souls, who can go into the highways and byways, lifting up and leading, advising and encouraging with the truly catholic benevolence of the Gospel of Christ.