School boards — an elected group of community members that sets policy, approves the yearly budget, and establishes a vision for a school district — haven’t been around forever.

In fact, school boards are a profoundly American invention. Puritans first passed the Massachusetts Law of 1647, which established the first public school system in America by mandating that communities of 50 or more households had to hire a schoolteacher to teach students reading and writing. Affectionately nicknamed the “Old Deluder Satan Act,” the law was created to ensure that all children could read the Bible and avoid the machinations of malevolent spiritual forces. Especially considering the difficult homesteading conditions and low literacy standards of the day, this public priority was groundbreaking.

As time marched on, variations on what we now call the school board evolved through organic efforts of community members to improve schools. After the American Revolution, school function and form took a prominent seat at the debating table. In his famous bill A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge, a bill that aimed to give three years of free education to free girls and boys, Thomas Jefferson outlined his beliefs about the purpose of public education.

[W]hence it becomes expedient for promoting the publick happiness that those persons, whom nature hath endowed with genius and virtue, should be rendered by liberal education worthy to receive, and able to guard the sacred deposit of the rights and liberties of their fellow citizens, and that they should be called to that charge without regard to wealth, birth or other accidental condition or circumstance; but the indigence of the greater number disabling them from so educating, at their own expence, those of their children whom nature hath fitly formed and disposed to become useful instruments for the public, it is better that such should be sought for and educated at the common expence of all, than that the happiness of all should be confided to the weak or wicked.

Education, therefore, was to be a truly liberal, publicly funded freeing of the mind for wealthy and poor alike so that the new republic could benefit from the best leadership possible. (While American education was not truly extended to all until 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education, it’s important to remember that Jefferson’s writings would have stood in stark contrast to the feudalistic pay-to-play attitudes elsewhere in the world at the time.) Partially through Jefferson’s influence, the school board, representing local interests, became an essential part of guaranteeing that schools could truly serve their constituents. Jefferson, for example, believed that a system that put education primarily in the untried, elite hands of the newborn government rather than local groups of parents “is a belief against all experience.”

The process of evolution struggled on, and by the 1820s, American school districts had what Professor Adam Laats calls “a pretty recognizable modern school board.” As the business of organizing schools grew ever more complex, the unpaid members of the school board tended towards educated, competent citizens and the paid position of superintendent was added in order to handle the weight of administrative tasks.

Jefferson’s ideal of a free public school system of “common schools”, a distinguishable ancestor of our system today, emerged in the 1830s. Schools began to be more open to girls in the 1840s. Restricted by the organizational difficulties of the largely rural nation, public elementary schools did not become commonplace nationwide until the late 19th century, with high schools only becoming popular in the 20th century.

According to the George Washington University’s School of Education and Human Development, 55 percent of children between the ages of 5 and 14 were in public schools in the 1830s, rising to 78 percent by the 1870s.

This emphasis on the community-led orientation of school boards has meant that, especially since the Progressive Era, school board races are often held in off-cycle election years, and ballots do not list political parties next to candidates’ names. Too much partisan political influence in the race, the argument goes, could lead to national donors and high-profile interest groups meddling in local schools to their great detriment.

School boards today rarely make splashy headlines unless a video of obscene or farcical behavior at a meeting goes viral, as they have unfortunately been doing in increasing numbers. It’s slow, tiresome work, especially for those serving in large urban districts. A 2002 American Enterprise Institute (AEI) study found that board members generally spent about 25 hours per month, usually unpaid, on board business. “Substantial numbers of board members, however-especially those in large districts-spend 20 or more hours a week on board affairs.”

At the same time, the term “school board” is invoked like a spell again and again on both sides of the aisle in the great ongoing battle of the “culture wars.” Everyone, it seems, believes that the health of the nation begins at the local level, when school board members possess robust characters and strong civic inclinations. Both sides tend to agree that a school board should 1) represent the local community, 2) act as strong, healthy vision casters for the school, and 3) fight for academic excellence.

As this civic institution evolves into the 21st century, is it fulfilling its purpose? Should the current national format of school boards be given medicine, and if so, what type and dosage?

Checking In

It’s important that the political makeup of school boards, in general terms, reflect the political makeup of their communities. While a political skew towards one party or another might simply reflect a superior, sophisticated party apparatus, it might also represent national interests and national donors manipulating the strings of these generally low-visibility elections.

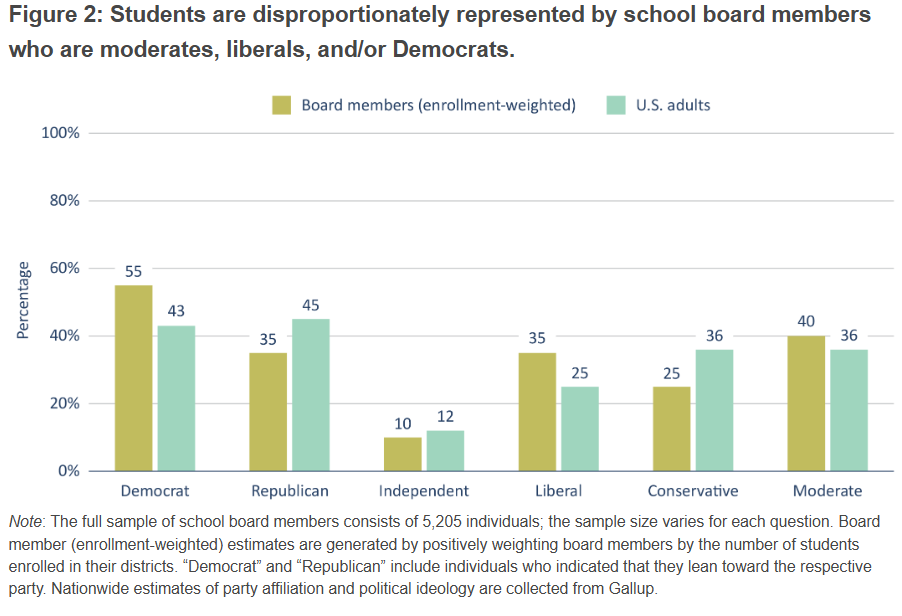

An October 2025 report by the Fordham Institute surveyed over 5,000 board members representing over 3,000 national school districts. Since the United States has over 13,000 school districts (most small, rural, and sparsely populated), this data does not fully represent all board members and districts. The Fordham Institute controlled for this sample with limited representation by weighing the results carefully: you can read about their method here.

The Fordham Institute found that nationally, school board members’ party ideologies and leanings map loosely onto the US public’s leanings. However, since most students are in urban areas, a high majority of students tend to be disproportionately represented by moderates, liberals, and/or Democrats, who tend to hold urban seats.

However, it also appears that two-thirds of school board members match the political leanings of their district. The Fordham Institute writes, “This pattern suggests that board–citizen mismatches are not the norm but they are also not uncommon. Moreover, these mismatches may be more common in less populated districts.”

So, school boards tend to represent their communities politically (though with limited success). However, they don’t necessarily reflect their communities demographically. School board members skew white, female, highly educated, and towards former teachers. This isn’t surprising when one remembers that the majority of school districts are in rural, white areas and that highly educated or former teacher board members are more likely to both be civically involved and elected for their professional competency. Once the Fordham Institute controlled for population, they found that over four-fifths of board members are of the race/ethnicity that is most common among their residents, but such board members represent only two-thirds of all students.

They also noted that if 1:1 ethnic representation did occur, it might not truly signify that board members match their community’s desires. After all, a white community might elect a black candidate because they believe that she will represent them better than the opposing white candidate might. Political leanings, not ethnicity or gender, likely tell a better story when it comes to accurate representation.

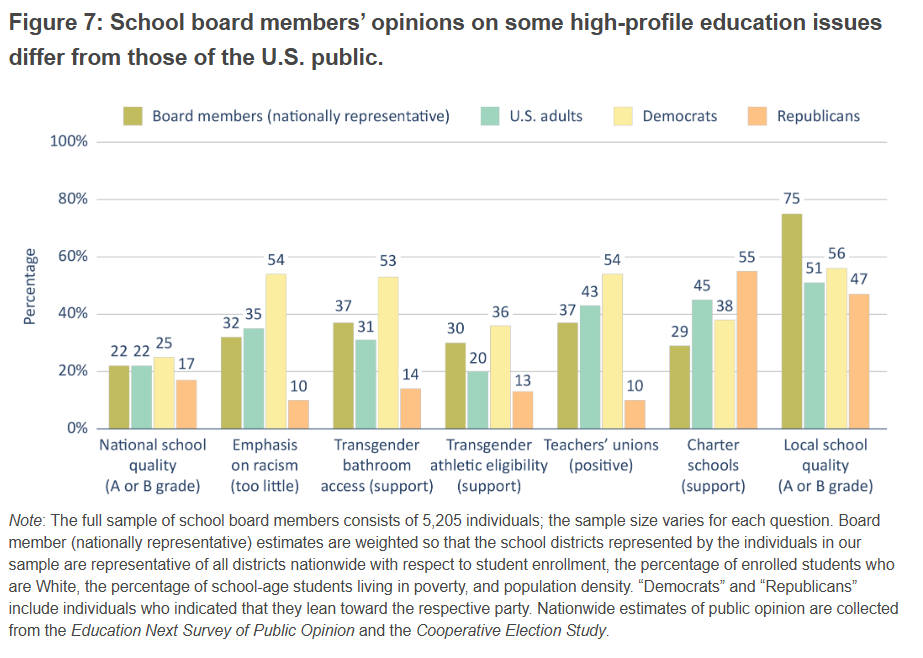

There are a few significant issues where the opinions of school board members tend to differ from those of the American public, including support for charter schools, transgender athletic eligibility, and, interestingly, local school quality. School board members were very likely to rate their school more highly than members of the community would rate their school.

However, when the data was analyzed while taking the population differences between dense urban centers and rural countryside districts into account, the Institute found that a majority of all students (generally, about two out of three) were represented by board members that have views that align with local politics. The Institute also noted that “only about half of school board members hold positions on recent polarizing issues that line up with the party affiliation of the majority of their residents.”

It seems that while the majority of school board members tend to drift more leftward than their communities, board makeups are still somewhat representative of the communities that elected them. But the cracks are widening, and have widened dramatically since a similar study conducted in 2002. Today, Hispanics tend to be underrepresented by school boards, and school board members are less likely to hold views commensurate with the average Black citizen than they are with any other group.

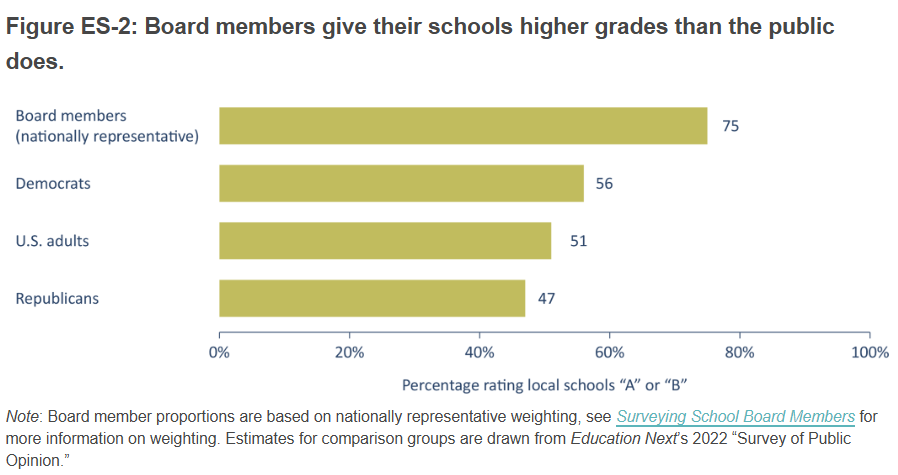

One piece of data was cause for significant concern: there’s a large gap between the public perception of how well schools are doing and how school board members rated their schools. School board members are far more likely to rate their schools higher than their community would rate them.

The consequences of incorrect perception, likely shaped by a natural inclination towards institutional loyalty and a desire to believe that one is doing a good job on a board, can have tremendous effects. Board members may ignore or dismiss systemic problems and pass budgets that don’t responsibly reflect district needs. They may feel immune to the checks and balances of the system that are represented by the ballot box. And, in an age of the lowest NAEP scores the nation has seen in a generation, it might mean that board members are casting aside their duty to steer the ship back to safety.

There’s no reason to believe that school boards as an institution currently strongly merit any type of creative structural overhaul. But reforms and refreshments are always a good idea. While reforms that aim to insert national partisan politics into local races (like listing party affiliation on the ballot) open the door to out-of-state donor control, other reforms can put the emphasis back on local community development. Local news interviews can ask candidates frank questions about what needs to change in their local school district. Districts and communities can take the initiative to plan local events that create strong connections and reject elite party control. And, too, accountability at the local level for poorly performing districts is an essential change.

Just as the original architects of the fledgling American school system predicted: the more robust the grassroots, the stronger the school.