The Learning Curve Leo Damrosch 10292025

[00:00:00] Albert Cheng: Hello everybody, and welcome to another episode, a Halloween special maybe episode of the Learning Curve podcast. I’m one of your hosts, Albert Cheng, and co-hosting with me this week is Helen Baxendale. Helen, what’s up?

[00:00:36] Helen Baxendale: Hello, Albert. It’s good to be back with you this Halloween weekend. Looking forward to our Halloween themed guest.

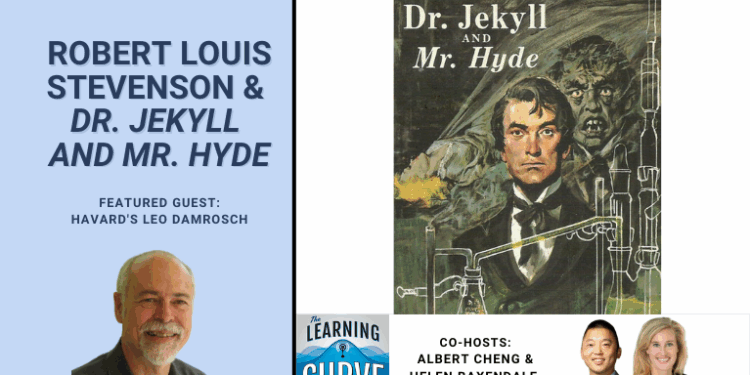

[00:00:42] Albert Cheng: Yeah, that’s right. If you don’t know, we’re gonna have Leo Damrosch who’s gonna talk about his new biography of Robert Lewis Stevenson. Now, what’s the connection to Halloween? Well, he is the author of the famous novel, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. So that’s how we’re gonna get our spooky on, I guess, but it should be exciting show.

[00:01:02] We’re gonna talk more about Stevens, not just Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, but stevenson’s life and some of his other works, which are classics as well. So looking forward to the show. Now, before we get to that interview though, we should talk some news, Helen, as we always do on this show. What caught your eye this week?

[00:01:17] Helen Baxendale: Well, thanks. He, yes. The article I was interested in this week was published on the, uh, the Substack of Robert Pondisco. Hmm. Who’s a well-known a EI scholar, but in fact it was a, a guest post by Douglas Carine, who is a long time ed policy expert. Actually a, I think now emeritus at the University of Oregon. But he has been, I think, one of the most consistent and powerful voices for the professionalization of teaching.

[00:01:44] And the idea that education needs to develop a set of standards around what qualifies as as actual knowledge and truth claims in education. And that, you know, the profession of teaching is sort of akin to where medicine was at a time when it was still talking about myas asthmas and affixing leeches.

[00:02:03] You know, in terms of its respect for evidence and how it deploys evidence in common practice. And so it’s a fascinating article. It’s an article that should make us all who are in education pretty angry because it, you know, sort of documents, I think all the ways that teaching isn’t really a true profession.

[00:02:21] Certainly not in the way that medicine is in terms of. Having cohered around a clear body of evidence and best practice in holding, holding the profession to such standards. I mean, the most obvious instance of this would be around early literacy instruction and the way that synthetic phonics is sort of waxed and waned in and out of fashion, and is only now sort of coming back into vogue thanks to the efforts of crusading journalists as opposed to education academics, by and large.

[00:02:48] We have Emily Hanford to thank more than we do necessarily the education establishment. So I would implore anyone who’s interested in the future of the teaching profession to take a look at this because I, I think it really couldn’t be more important that education really finally, you know, belatedly, coalesces around an empirical practice around, you know, what works, why and how do we ensure that that becomes common practice.

[00:03:15] Albert Cheng: Yeah, I mean, I think this is a conversation that’s been happening for many decades now. Oftentimes, you know, folks for a while have been pointing to medicine, even, you know, the area of law to look for, you know, professional practices. And certainly education research is also well behind the curve. I mean, it seems like we’re steeped in it now, but the quality of evidence that we have and the amount of evidence that we have for things is actually only, uh, I mean, in earnest, really, it’s only been accumulating for the past 20 years.

[00:03:42] I mean, you know. Free to early two thousands wasn’t much by way of education research, at least compared to now. So certainly outta room to expand. And I’m curious to get your take on this. I know at Great Hearts I know you guys like to think of things in terms of traditions and in some sense you could think of different professions as having a tradition around it.

[00:04:03] And if you’ve kind of understood tradition. Understand traditional, a bit broadly about clarity around ends and maybe kind of established practices to achieving those ends. What do you think about that analogy? To think about the teaching profession? So not simply being guided by empiricism for empiricisms sake, but to think of it broadly in terms of, uh, a tradition and encoded wisdom, I guess, of the ages in that.

[00:04:27] Helen Baxendale: Albert, it’s a great question and I, I wish we could do an entire episode actually on the fascinating point you’ve just raised around, you know, what are the actual, the limits of empiricism in terms of deciding, you know, how an education should be organized and the whole question of, you know, sort of normative ends.

[00:04:45] There’s a whole lot about education that, you know, sort of just. Empiricism has nothing to say on, and that is, you know, what, what are we actually trying to produce at the end of all of this? What are the ends here? So I completely concede the point that, you know, empiricism isn’t the whole game. What really grinds my gears though, is when we are in the realm of, you know, an empirical question, like what is the.

[00:05:09] You know, technically most effective way, or the best bet for maximizing the number of kids who can read fluently by third grade. And we know that, you know, synthetic phonics is a far higher success strategy than, you know, whole language or other strategies that have been used over the years. And there just seems to be this stubborn refusal by many in the profession still to embrace that evidence.

[00:05:33] Now, why do we want kids to master reading? Is it just simply for technical proficiency? No, we want them to master reading so that they will have the great pleasure and enrichment of, of reading, you know, the best that’s been thought and said over the ages and become, you know, thoughtful and, and aesthetically alive human beings, which has nothing to do with, you know, randomized control trials.

[00:05:55] So everything in its proper place for sure. And I love this conversation around the tradition versus more recent methodology around what works. You know, I think there’s a really. Rich dialogue between those two sort of ways of knowing that classical education has to engage with perhaps more than it necessarily instinctively does.

[00:06:15] But I guess I’d also make a pitch here for the classical tradition, insofar as very often, what becomes tradition, whether consciously or otherwise, is because it works.

[00:06:25] Albert Cheng: Yeah, yeah.

[00:06:26] Helen Baxendale: Things in Dua because. Because they have an inherent merit.

[00:06:30] Albert Cheng: That’s right.

[00:06:30] Helen Baxendale: Uh, and very often it’s, you know, it’s the social scientists who come along afterwards who provide this sort of newfangled rationalization, but the folk wisdom has known this for a long time.

[00:06:41] So we’d love to continue this conversation. Albert, I think you and I would have have a lot to discuss, but we best move on and, and hear about your story of the week.

[00:06:50] Albert Cheng: Just real quick, it’s a story on a new program aimed at training teachers, particularly in rural areas in the country, on providing effective civic education.

[00:07:01] So the National Constitution Center based in Philadelphia. They’ve just announced a three year project where they’re going to recruit teachers that demonstrate excellence in teaching Civics to serve as fellows to kinda go around the country and provide some professional development to other teachers, particularly rural areas to do the same.

[00:07:21] So this is a tall order, ambitious endeavor. So I’m gonna keep my eye out to see how this all works out, but this is challenging at TIP to the National Constitution Center for trying to do this.

[00:07:33] Helen Baxendale: Yeah, it sounds like a great initiative and, um, teaches, teaching teaches is often a, an effective strategy, so wishing them the best with that.

[00:07:41] Albert Cheng: Yeah. And maybe there’s some wisdom to that. Well, anyway, hey, let’s continue and, and on the flip Sydor the break, we’re gonna have Leo Dam Ross join us to talk about Robert Lou Stevenson. So stick around.

[00:08:04] Leo Damrosch is the Ernest Birnbaum professor of Literature emeritus at Harvard University. His books include Storyteller, the Life of Robert Lewis Stevenson, Jonathan Swift, his life and His World, the winner of the National Books Critics Circle Award in biography, and one of two finalists for the Pulitzer Prize.

[00:08:21] In biography, eternity Sunrise, the imaginative world of William Blake, a finalist for the National Book Critic Circle Award in criticism, the Club Johnson Boswell and the friends who shaped an age named one of the 10 best books of 2019 by the New York Times. Jean Jacque Rousso Restless Genius and National Book Award finalist for nonfiction and winner of the Winship Penn New England Award.

[00:08:44] For nonfiction, he earned a ba summa cum laude from Yale University. Was a Marshall Scholar first class honors at Trinity College Cambridge, and received his PhD from Princeton University. Professor Damrosch, it’s great to have you back on the show.

[00:09:00] Leo Damrosch: Thank you very much for inviting me.

[00:09:01] Albert Cheng: Yeah, I mean, we’ve talked about Jonathan Swift with you, Tova with you.

[00:09:05] I believe I, I have to just add in after our last interview, I’ve read Giy of Rousseau in preparation of teaching a meal, so I really found that enlightening. So I’m really grateful for your work.

[00:09:17] Leo Damrosch: Oh, thank you. And I, I’ll just mention in passing, I began writing very academic books, which you gotta do if you are an academic, but the Rousseau was the first time I actually wrote a biography for people.

[00:09:28] Albert Cheng: Yeah, yeah, yeah. No, it’s very accessible. I and I, and, and very colorful.

[00:09:31] Leo Damrosch: Thank you.

[00:09:33] Albert Cheng: But hey, let’s talk about your newest biography, Robert Lewis Stevenson. So storyteller, the life of Robert Lewis Stevenson is, the title is Receive Wise Praise from New York Times, wall Street Journal, Washington Post, the Economist.

[00:09:46] And we’re kind of doing a, a, a little Halloween episode of, so we’re gonna mention Stevenson probably most. Well known for writing the 1886 Gothic horror novella, the strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which we’ll talk about in a little bit. But why don’t you sketch for us an overview of Stevenson, you know, his life and why his literary work is so important.

[00:10:09] Leo Damrosch: Well, I’ll start with the second part of that, and I know we’ll come back to his life. He was born in 1850 in Edinburgh, in Scotland, had a Scottish accent. All his life was Scottish and not English for sure. Born in 1850, died in 1894 when he was only 44 years old from a stroke. At that time, after much adventuring, he was living with his family in Samoa, where they had bought a plantation.

[00:10:33] He was always restless and adventurous. And we’ll come back to Samoa later on. But that actually gave me my title because he was very close to his Samoan friends learned their language. They regarded him as a kind of champion of their cause. We’ll talk about that, I’m sure also. And they named him Tus, which means storyteller.

[00:10:52] And I thought, yeah, that should be the title of my book. ’cause that’s exactly what he was. One other thing I would say, he was always experimenting. One of his closest friends was Henry James, and you couldn’t find two. More different novelists, but they respected each other as fellow artists and he was always trying something new.

[00:11:11] And in fact, Dr. Jack Lou, Mr. Hyde is not typical. He never wrote another thing like that except maybe a couple of very short stories, and it wasn’t his favorite work of his own, although he understood why it had great popular.

[00:11:24] Helen Baxendale: Professor Damrosch, I wondered if we could prompt you to tell us a little more about the early life of Robert Lewis Stevenson In storyteller, you write that quote, the most important person in Lewis’ life was neither his mother nor his father, but Allison Cunningham always called Cumy, who arrived when he was 18 months old to be his nanny or nurse.

[00:11:45] Can you briefly tell us about. His family background and some of the formative intellectual influences, as well as how his adventurous childhood helped shape his career as a a writer.

[00:11:56] Leo Damrosch: Well, his family were known as the Lighthouse Stevensons because his father and his grandfather and a couple of uncles all were designers, civil engineers of the very first lighthouses on the very dangerous, rocky, Scottish coast they built.

[00:12:12] Dozens of them, many of which are still standing and in use. And it was just taken for granted that he was the only son of Thomas Stevenson, uh, would follow in the family footsteps. But he was awful at math. And it just became clear that he was never gonna be able to do that. So they said, well, you better be able to support yourself.

[00:12:32] Why don’t you get a law degree? And he loyally did that and passed the bar and never practiced one minute in his life, and indeed relied on his generous family for support until. Well into his thirties when he finally began to be a very successful, popular writer. The thing about Cumi that is so interesting, she was very intelligent, had a good education, which was not uncommon in in Scotland, in her case for a fisherman’s daughter.

[00:12:57] Very dramatic personality. I think he learned a lot from her about storytelling, but she was a Scottish Presbyterian in a very severe Calvinist mode. More severe than his parents were. And she filled him with dread of eternal damnation. And being an imaginative little boy, he would wake up desperately sweating with fear, afraid he was gonna be dragged before the great white throne and judged.

[00:13:24] And it’s interesting that although like many writers like James Joyce, he lost his faith in adult life. That deep sense of some kind of inner dividedness of some kind of war within which comes right out of St. Paul, always stayed with him and that absolutely is the hidden text of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and I know we’ll talk about that novel some more.

[00:13:45] Intellectual influences. It was not so much his education. He cut classes as often as he could, and it was law classes anyway. It was just constant. Lifelong reading became flu in French, he read French as easily as English. His influences were enormously varied. The other thing to mention is. He had a very dangerous lung condition.

[00:14:05] Later on when the bacillus for tuberculosis was identified, specialist said That’s probably not what he had, but it was certainly dangerous. He would cough up pints of blood. It might’ve killed him at any time, and he spent months on end under doctor’s orders, confined to bed, reading and writing, and in fact, telling himself stories and inventing stories was essential to sort of escape from his physical condition.

[00:14:32] Albert Cheng: Wow. And so let’s talk about some of the stories that he’s written. In your biography, you write quote, I try to illuminate Stevenson’s achievement as a writer more fully than others have done. They seem often to assume that his works are already familiar to readers, which is generally not the case. End quote.

[00:14:50] Readers may or may not be familiar with Treasure Island kidnapped. I mean, I know I have a copying on my shelf somewhere, a child’s garden of verses. But not everyone does. So why don’t you fill in the gap there. Tell us briefly a couple of the overarching themes of his major works, you know, or his travel writings, poetry letters that deserve wider understanding and appreciation.

[00:15:12] Leo Damrosch: Well, I’d start by saying again that he was always experimenting, always trying something new. He wrote dozens and dozens of essays on all kinds of subjects, some of which are. Very interesting and enjoyable. He was a travel writer right from the beginning. He wrote about a kind of kayak trip that he and a buddy took in canals in France for not a very exciting trip, but getting out and he, he describes a kind of Buddhist oneness with.

[00:15:36] You know, letting your consciousness drift with the boat. They’re very interesting. He took a journey on foot in the mountains in the middle of France after his heart had been broken by the woman. He did ultimately get to marry, but she had left for her Native America and he didn’t know if he’d ever see again.

[00:15:53] It’s called travels with a donkey that was to carry his luggage. And again, it’s kind of fascinating. Really interior voyage, trying to find out who he was and be all by himself in a strange place. Then he wrote poems. As you mentioned, everybody used to have a child’s garden of verses read to them when they were little, and they’re interesting because they are very much the weirdness of adults as seen from.

[00:16:18] Child’s perspective. They’re not written down to children. There’s as if the children could have written them. Henry James said those are poems a child could write. If a child could see childhood from the outside. They’re really fascinating still to read themes for his fiction. I don’t know that you could say that because so many of them are different and we’ll talk about too, our church, treasure Island and Kidnapped.

[00:16:40] I can say more about those, but they have little in common with each other except. Adventure and immediacy. He thought the fiction of his own time, what we think of as Victoria novels, were overwhelmingly detailed and sort of boringly realistic. And what he wanted was energy and excitement and movement.

[00:17:00] And he said he wanted his writing always to be kinetic, not static. And I think that’s his genius. He makes you feel what it would be like. To be escaping from pursuing soldiers through the Scottish Highlands or to be threatened with death by a mutiny of pirates on your trip that went to find treasure.

[00:17:19] And it’s that immediacy that I think a lot of very great modern writers have praised in Stevenson. Fans of his that you might not expect will probably. Mentioned those two. He said quote, one thing he said, uh, can’t say later life ’cause he didn’t live so long. But he said there were really three things.

[00:17:36] He especially loved books, women and adventure, and people suspected it was adventure, most of all.

[00:17:45] Helen Baxendale: Profession. Let’s stick with that kinetic sort of atmospheric theme. ’cause I think that comes through in strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which follows Mr. Addison, a London-based lawyer who investigates a series of strange occurrences between his friend Dr.

[00:18:02] Henry and a murderous criminal named Mr. Edward Hyde. And you write in storyteller that. Bogies, the Scottish word for ghosts or specters had been part of Stevenson’s consciousness since his earliest days, featured in the stories that Comey used to tell and then recalled in a child’s garden of verses.

[00:18:21] And since we’re coming up on Halloween, I wondered if you could offer a prey of Jekyll Hyde’s horrifying plot.

[00:18:29] Leo Damrosch: Happy to do it, by the way. It’s interesting. Uh, most publishers to this day put the word the, in front of the title, the Strange Case. Ashley Conan Doyle didn’t start writing his Sherlock Holmes stories till a year or two after this novel.

[00:18:42] And it’s not one case among many. It’s, it’s strange is the important word, that it’s a weird one of a kind story, not something that a detective would solve. In fact, there though, there have been movie versions. It literally. Cannot be filmed the way Stevenson conceived it, because here’s the story. Dr.

[00:19:00] Jekyll is a very respectable London physician, and he has impulses that he is kind of scared by to do something dangerous or even sadistic. And of course he doesn’t allow himself, but he feels this pressure rising and he invents a potion, which when he swallows it, will let him be transformed into his evil self.

[00:19:22] And that’s a. Kind of D fish, creepy looking guy, but not a monster. Just something strange about him that people find disturbing. And that’s Edward Hyde, who also looks quite a lot younger than he is because it’s liberating impulses that the adult physician has been suppressing. And the reason it can’t be filmed is that.

[00:19:43] Jekyll’s closest friends become aware that this weird person has got a key to Jekyll’s house and is letting himself in sometimes, but it never occurs to them as the same man. And if you film it, it’s gotta be the same actor and you’re gonna know from the very first scene. But the whole point of the novel is you don’t find out until the very end.

[00:20:04] And Jekyll finally commits suicide because he realizes increasingly he’s unable to stop turning into Mr. Hyde. And if he doesn’t kill himself, he will be a permanent monster. And they learn this only at the very, very end. And so it’s not so much a detective story as a revelation of the impulses for evil in all human beings.

[00:20:27] And that’s the Calvinism that Stevenson never outgrew what St. Paul calls the war within our members, inside our our bodies. And what if you could liberate that and why wouldn’t it try to take over? So it’s really an extraordinary one of a kind story that it works brilliantly on the page to this day.

[00:20:46] But of course we all kind of know that. Jekyll and Hyde are the same person. ’cause we picked that up before we ever read the novel. So in a way, you can’t read it the way he wanted it read where it just bowls you over when you find out what was really going on.

[00:20:59] Albert Cheng: I suppose at this point, you know, it’s a little late for a spoil alert for our listeners, but as you say, I think our listeners probably already know this.

[00:21:07] Professor Dammar, I’d like to have you say a bit more about that theme, what you’re saying about how Stevenson uses Mr. Hyde. To reveal something about human nature, the evil residing within human nature. I mean, you know, great literature always has something great to teach us. But actually before I let you answer, I, I mean, I do want listeners to hear just Stevenson’s description of, of Mr.

[00:21:27] Hyde, and then I’ll, I’ll let you weigh in on this. So Stevenson writes, quote, Mr. Hyde was pale and D fish. He gave an impression of deformity without. Any Nameable malformation. He had a displeasing smile. He had born himself to Mr. Terson with a sort of murris mixture of timidity and boldness. There is something more.

[00:21:48] If I could find a name for it, God bless me. The man seems hardly human. Something retic, shall we say. What does Stevenson want to convey and reveal about human nature with that?

[00:22:00] Leo Damrosch: I think that human nature is in fact selfish and very capable of doing very bad things to other human beings. He was not sentimental that way, although he himself was a kindly and generous personality, but I think he felt that we all have that within, and you quote that word, it’s a very apt that you did.

[00:22:21] Tralo, tra Luddites would be like cavemen. Primitive humans, and there was a theory that he was interested in. Got into a couple of his stories too, that we have evolved gradually to become more and more civilized. Of course, he didn’t even live to see the first World war and let alone the second, and it would not have surprised him if he had lived to see that, that in fact, once you liberate it, human beings can do the most dreadful things to each other, and so it’s like an istic, you know, return to some kind of primitive.

[00:22:53] Layer in ourselves that poor Dr. Jekyll has liberated with this potion that he thought was going to greet him to have be a happy man and banish his bad self to kind of occasional misbehavior. But once you let the bad self emerge, it becomes your whole self. And that was what Jekyll was experiencing.

[00:23:13] Helen Baxendale: Let’s switch gears for a moment and you, you’ve spoken already, professor around the extraordinary sort of versatility of Robert Lewis Stevenson. So we have the extraordinary sort of visceral horror of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and then we have these amazing adventure stories of, you know, treasure Island and kidnapped.

[00:23:31] Tell us a little bit about those two, if you would, and what they convey about Stevenson’s, sort of imaginative capacities and, and talents as a writer.

[00:23:40] Leo Damrosch: Well, they used to be dismissed as children’s books, or I’m afraid as boys books because Treasure Island is about pirates and buried treasure and its hero.

[00:23:50] And narrator is a teenage boy named Jim Hawkins. But Hawkins is describing it when he is older and wiser and trying to understand what he is been through. I think it does see life from a very adult perspective. Before Henry, James and Stevenson ever met, James wrote a very. Positive review of Treasure Island.

[00:24:08] He was extremely impressed by how skillful that book is, and it’s really about finding out who you can trust and ultimately finding out who you are, which so many great novels by Stone Doll and George Elliot and all kinds of other writers have also done. Jim is sort of captivated by a charismatic guy who he believes is just a ship’s cook when the hispanica, the name of their chartered vessel sets forth to find a buried treasure that they’ve got hold of a map that shows it’s probably in the Caribbean somewhere that they could go and dig up.

[00:24:43] And in fact, the pretend cook is a. Pirate leader named Long John Silver, probably heard of his name, stumping around with one leg, like a friend of Stevenson’s that he was very fond of. Very powerful magnetic personality, and Jim has to realize that although this guy has his. Smiling side. In fact, he’s the kind of sociopath and he will kill without a moment’s hesitation if he needs to.

[00:25:10] So you end up realizing that this figure you’re so drawn to, because he is so imaginatively powerful, is also has to be your enemy. And by the end, it’s a sadder and wiser Jim, because sure, they got the treasure and they brought it back to England and they got rid of the pirates and all kinds of adventurous ways.

[00:25:29] But he doesn’t feel happy about it. He is been through a lot and the treasurer seems to have kind of lost its point. So I did talk about kidnapped, very different book. But also a book about what it’s like to figure out who you are under stress. The narrator and hero. There is a guy named David Belfor, uh, who finds out to his surprise after his father’s death that his father was the proper heir of a family fortune, which an uncle has unjustly gotten.

[00:25:56] And David goes off to try to see if he can recover his birthright, and instead the uncle has an. Kidnapped aboard a ship that’s gonna take him to the colonies and be a virtual slave. But luckily, I can’t tell you the whole story, but he escapes and travels on foot through the highlands of Scotland with a kind of a rebel who represents everything, the very proper upright.

[00:26:19] David is not named Alan Breck, who actually existed in history and again, is finding out, you know, he is growing up, who can I trust? Who am I? And again, it ends in a kind of a down note. So he does get his inheritance after all, but Alan Breck has gone to France because his under sentence of death if the English catch him.

[00:26:38] And it’s like the most important thing that’s happened to him. Finally he’s lost. And again, it’s the energy, the, the excitement of actually what it would be like if you have to leap across a rushing stream, because that’s the only way to escape the British troops who are hot on your heel and these moments of crisis that you have to live through.

[00:26:59] A friend of Stevenson said, you described that scene so well. I can absolutely visualize it. Stevenson said, you read it again. There’s not one adjective in there. There’s no descriptive word. I’m just telling you what it felt like to be trapped in that moment. And so that’s a historical novel said in Scotland, a hundred years before Stevenson’s time, treasure Island is a adventure that’s set in a.

[00:27:21] Caribbean, which at that time he’d never visited. And I think it suggests his hour to recreate a story, which is why I call him storyteller in a way that most Victorian writers weren’t doing. And it, it was said by Italo Calvino, modern master who admired Stevenson, that the reason he writes boys books is because.

[00:27:42] That’s the only way not to seem to be making fun of it and parodying it because the boy does have openness and innocence that the reader can share vicariously.

[00:27:53] Albert Cheng: So let’s talk about the latter part of his life. You’ve mentioned earlier how he in 1890, along with his American by Fanny, settled in Vima Samoa and there he became deeply concerned about the expanding European and American influence in the South Pacific Islands.

[00:28:12] As well. You know, that’s, you know, eventually as, as you mentioned earlier, he, he had poor health, died of a stroke at the age of 44. Fill those gaps for us now. I mean, talk about his marriage. What was his life like in Samoa? What happened to his wife and childhood nanny after he passed away? Tell us about that.

[00:28:30] Leo Damrosch: He had sort of, um, pep in love affairs with a few proper Edinburgh girls from the class that he grew up with, but they were pretty repressed and very proper and wouldn’t even make eye contact. And actually the women he had the most relationship with, and he was never ashamed of it, was Edinburgh Prostitutes whom he sympathized with deeply.

[00:28:50] They were making the best of a. Rough life, they, they’d been dealt a bad hand of cards and he thought many of them were very good human beings, and it was very sincere and they were very fond of him. And the way he met his wife, Fanny, was she had broken away from her husband in America who was not a bad person, but just a continuous adulterer and was just making her miserable.

[00:29:13] And she took her three children with her, and because she was studying art, went to France all by herself, that is with, with her kids, and enrolled in an art school. And then the youngest boy died of a very rapidly advancing tv. Which was heartbreaking. She said there rest of her life, there was never a day that it wasn’t in her mind.

[00:29:33] And her friend said, you ought to go to this artist colon in a little river outside Paris and try to recover. And Stevenson was just coming back with his buddy from that kayak trip and looked into the window of the hotel where. She and other artists were dining and he said afterwards that that was the moment he fell in love.

[00:29:51] It really was love at first sight. It took her a while because she had her grief to deal with and she did finally go back to America, see if one more chance for her husband. It didn’t work out, but almost certainly she sent him a message. If you think we’re ever gonna be together, come here right now, or I’m not going to.

[00:30:10] You anymore. And he did it. Most daring thing he ever did in his life. There’s an old hymn that begins once to every man. A nation comes the moment to decide. That was his moment. He threw everything aside, took passage on a cheap immigrant boat, reached New York, got sick, crossed the American continent, and a crummy immigrant train, and rejoined Fanny.

[00:30:31] And pretty soon she got her divorce and they got married and he said that was the best thing he ever did in his life. She had enormous energy. She had lived for years in mining towns in the west. She was a crack shot with a pistol. She was very, very intelligent. She not only nursed him through his illnesses, he probably would’ve died long before he did die, but was his best critic.

[00:30:55] I’ll give you one good example. He had written the first draft of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. He was delighted with it. Brought it to in front of the fireplace where the stepson and his, his wife were, and read it to them, and she didn’t respond very positively. She just sort of gazed into the fire glumly and he wanted to know why, and she said, well, you’ve missed the whole point, because he had made it.

[00:31:16] Just a guy who puts on a disguise and goes out and does burglaries and things at night, and you always know it’s him. And it was the divided self was his theme. And she knew him well enough to know that he said, you’re right. And he threw the whole manuscript into the fire. Shocking them both, but he said, it’s no use.

[00:31:33] I can’t just tinker with this thing. I’m gonna start over. And he wrote the books that we know. So it was a very powerful relationship in every way. And she was as adventurous as he was. So indeed the travel was exactly what she wanted to do. And when he finally made a lot of money from his novels, it became very popular.

[00:31:51] They always wanted to cruise the ocean, not the Atlantic, but the great Pacific Ocean. And they chartered a boat, which had its own captain and crew, and they sailed all over the Pacific and stayed for months at a time in Tahiti and other islands. Always made friends there. They had absolutely no racial prejudice.

[00:32:09] Everything about them is attractive that way. And when they got to Samoa, unlike those little aals, which many of the islands are. It’s a very mountainous set of islands, some of them quite large, and they found they could buy several hundred acres and have a plantation. Maybe it would even support them. I don’t think that was ever gonna happen, but they really settled there and belonged there and had no wish ever to go back to Europe.

[00:32:32] And Stevenson’s health improved tremendously. That climate and the lifestyle suited him. And the reason he became the champion of the Samoan people was. That was when the so-called great powers were carving up all of the islands of the Pacific. That was when Tahiti, for example, had recently become French, as it still is.

[00:32:51] It’s still a Department of France and people speak French there, and United States was just about to acquire the Philippines and Puerto Rico. Indeed, Hawaii, which was not yet part of the United States, and it was all to exploit those places and at the expense of the people who lived there for many, many generations.

[00:33:10] And Stevenson became a hero to the Samoan people because he would publicize what was going on there. And because he was a famous writer that London Times would give him long, long columns, and he probably really did make a difference.

[00:33:26] Helen Baxendale: Last question in two parts. You alluded earlier to the praise that Stevenson garnered from contemporaries like Henry James and you know others, including Conan Doyle, pro Twain, Kipling, ov, and Borges.

[00:33:41] And in, in 2018, he was ranked just behind Dickens as the 26th Most. Translated author in the world, could you tell us a little about why his literary legacy endures and, and what you hoped teachers and students of the present day would most remember about his life and stories? And then if you would be good enough, professor de Rush, we would love to hear you read a paragraph from a Stevenson story of Your Choice closes out.

[00:34:08] Leo Damrosch: I guess I would stress two things about his writing. One is the extreme clarity and simplicity that he strove for. His books are compelling reading. They certainly are page turner’s, but they didn’t start that way. It’s endless revision that a, a true craftsman puts his work through to give you that sense of speed and effortlessness.

[00:34:30] But he once said the art that he most wanted. Was the art to omit how to put strike things out. It was fun writing them, and you like what you wrote, but it is slowing down the story. And he was very gifted at that, and I think that’s the reason why those writers you mentioned admire him so much because they saw him as a craftsman who really was a master of achieving the effects that he wanted.

[00:34:54] The other thing is, I’ll say more about the love of adventure. Which is appears in most of his books though, Matt Jekyll and Hyde, which I said is not typical. Lemme illustrate it this way. When I was a young man, Hulk King’s, Lord of the Rings was much condescended to by literary critics who thought it was just, you know, pot boiler.

[00:35:12] And then many novelists thought it wasn’t real novels at all. Well, it has outlived nearly all the Pulitzer Prize win of those days because it turns out it’s a kind of. Masterpiece and it’s a masterpiece is storytelling. And there’s a great quote from CS Lewis that I’d like to give you, and then I will give you a Stevenson quote.

[00:35:31] Lewis said, in a family of very literary people who are always arguing about literature, the only person having a real imaginative experience might be the kid. With a flashlight under the covers reading Treasure Island. And that was the book he actually named. And I’m sort of paraphrasing, CS Lewis now.

[00:35:51] He said the story should turn on danger and hair breadth escapes. It should excite curiosity and finally satisfy it and the reader should participate vicariously. And Lewis concludes now I am quoting to have lost the tale for Marvels than adventures is no more a matter of congratulation. Losing our teeth, our hair, our palette, and finally our hope.

[00:36:15] And I already mentioned Vinno saying in a Victorian era that despised, heroism and romance, the only way to create it without making it a parody and ridiculous is to see it through the eyes of a boy. Then finally, you asked me to read a paragraph. I won’t read my own writing. I’d rather read Stevenson’s.

[00:36:34] I’m trying to give you an example of the immediacy with which he puts us inside a critical moment in Treasure Island. The pirates have begun to be defeated by the good guys, and the ship has been cast adrift and is floating just, and Jim realizes that if he could paddle out there on a little boat that he’s found he might actually be able to save the ship for his friends.

[00:36:56] When he gets there, two pirates have been on that ship but have had a fight, and one of them is dead and the other is sort of crawling around on the deck because he’s been wounded. But he comes after Jim with a knife. And so Jim scrambles up a mast and now he’s up high where the guy can’t reach him. And so the pirate starts, uh, kind of sweet talking him and saying, well, young Jim, I think you’ve gone now and, and I’m just gonna read what Stevenson tells us next.

[00:37:23] I was drinking his words and smiling away, went all under breath back, went his right hand over his shoulder. Something slang like an arrow through the air. I felt a blow on a sharp pang, and there I was tinned by the shoulder to the mast in the horrid pain and surprise of the moment. Both my pistols went off and both fell out of my hands.

[00:37:45] They didn’t fall alone with a choked cry. He loosed his grasp on the shrouds and plunged headfirst into the water. He rose once to the surface in a lather of foam and blood, and then sank again for good. As the water settled, I could see him lying, huddled on the clean, bright sand, a fish or two whipped past his body sometimes by the quivering of the water.

[00:38:08] He appeared to move a little as if he were trying to rise. He was dead enough for all that being both shot and drowned and was food for fish in the very place where he had designed my slaughter.

[00:38:20] Albert Cheng: Amazing. We’re just sitting here reveling in that description. I can almost smell the smoke coming from the pistols in what you were reading.

[00:38:29] Professor Dam Ross, thanks so much for taking the time to be with us on the show. It’s been my pleasure and thank you both.

[00:38:49] Well, Helen, how much Robert Lewis Stevenson have you read? You know, I, I only remember kind of browsing through Treasure Island as a little kid, and so this was fascinating to just listen to Leo Damrosch, talk more about the life of the author and, and some of his other works.

[00:39:01] Helen Baxendale: Yeah. Very similar situation for me.

[00:39:03] Albert. Albert, I think I read Dr. Jackal and Mr. Hyde as a kid and, and was. Maybe familiar with some sort of Jeju adaptation of, of Treasure Island, but, uh, it certainly wet my appetite to revisit. It was a, yeah. Great interview. Well, a thanks for co-hosting. Again, always fun to have

[00:39:22] Albert Cheng: you on the show. Likewise, Albert, it is always a pleasure to join you.

[00:39:27] Alright, and, uh, lemme leave everybody else with the tweet of the week. This one is from Education. Next quote. Meanwhile, in Indiana this year, lawmakers passed a bill. That eliminated the income cap on its choice scholarship program, giving 100% of students statewide funded eligibility. And this is an article at Education Next, talking not just about private school choice programs and states moving towards universal eligibility, but now making our arguments that Universal eligibility also needs what they call universal funding.

[00:40:00] Families are eligible, but as the authors argue, it means a little if the funding is not there to afford them of this opportunity. So check out that article and then make sure to tune in again next week for a new episode. On this podcast, we’re gonna have Kelly Brown, who is a social studies and government teacher at East Hampton High School.

[00:40:21] A former Massachusetts teacher of the Year. She’s the driving force behind the Bay States. We the people, the citizen, and the Constitution 2020 National Civics Contest Championship. So looking forward to that episode. Hope you are too. So join us next week, but until then, happy Halloween. Be well. Hey, it’s Albert Cheng here and I just wanna thank you for listening to the Learning Curve podcast.

[00:40:46] If you’d like to support the podcast further, we’d invite you to donate to the Pioneer Institute at pioneerinstitute.org/donations.