The cost of a state university education in Illinois increased 66% between 2009 and 2025, $6,028 more in tuition and fees per year. Blame declining enrollment, a bad state funding formula, pensions and high administrative costs.

The average price of attending a state university in Illinois increased by 66% between 2009 and 2025, costing in-state students about $6,028 more a year, according to Illinois Board of Higher Education data.

The average price of tuition and fees at Illinois’ dozen public universities rose to $15,439 this year from $9,410 in 2009, the earliest data available.

Costs outpaced inflation by 16% on average at the 12 state universities. The only exception was the University of Illinois-Chicago.

A post-secondary degree has proven to be one of the clearest paths for individual success and workforce advancement, said Jim Applegate, former executive director for the Illinois Board of Higher Education, a university professor and educational consultant.

“There may not be any silver bullets in life, but at a time when income equality is at an all-time high, the closest thing we have to a silver bullet to lift families and individuals into the middle class is to ensure they acquire post-secondary credentials,” Applegate said.

He said the Georgetown University Center for Education recently projected that between now and the early 2030s, nearly three-quarters of all jobs will require some form of post-secondary education.

“But we’re making it harder for the people who most need the degrees and credentials to get them,” Applegate said. “We need to find a path forward that promotes college opportunity success and efficiency in higher education for the good of our workforce and students in Illinois.”

Students now pay for the majority of university budgets

As tuition has risen, so has the share of university revenue coming directly from students. A Center for Tax and Budget Accountability report found 64.1% of state university revenue in fiscal year 2021 came from tuition and fees. Two decades ago, that share was just 28%.

This reliance on raising tuition prices to balance overburdened university budgets has driven the price of in-state tuition and fees in Illinois to the sixth-highest in the nation, according to the most recent data.

“I know the idea out there now is that higher education is no longer affordable. The problem is it’s not as true for people in the upper middle and upper class,” Applegate said. “Where the increase in higher rate costs are really taking a toll is with the middle class and low-income families.”

“For example, when I went to college, back when Moses was still around, the 70/30 split was common,” Applegate said. “The state covered 70% of the cost of college or more, and the tuition, institutional development and grants picked up the rest. But now we’re at a place where students are paying ever more of the costs.”

But how can public universities cost Illinoisans so much more when there are over 16,500 fewer students in the system and state spending on higher education has increased by $1.2 billion, adjusted for inflation?

It’s not a matter of underfunding higher education. Illinois already spends the most in the nation per full-time higher education student across its 12 public universities and 48 community colleges. It spends the second-most per full-time student on four-year public institutions.

Shrinking enrollment, growing state pensions, administrative growth and a poor funding formula are mainly to blame.

Shrinking enrollment, poor funding formula worsen tuition increase

The number of students attending Illinois’ public universities fell by 8% since 2009, meaning the system now serves about 16,537 fewer students. Among the universities, nine lost enrollment, with five losing more than one-third of their student bodies during those 16 years.

While the University of Illinois-Urbana and University of Illinois-Chicago have seen significant enrollment growth, and Illinois State University experienced modest growth, attendance at every other public university has dropped.

But under the current higher education funding model, the proportion of higher education dollars provided to them remains fixed.

State appropriations for higher education are based on historical precedent, not on enrollment or performance. Each university receives the same percentage increase year after year, regardless of how inefficiently they spend or how poorly they attract students – effectively punishing responsible schools.

“Illinois, like many states, has a funding formula that is a little bit upside down,” Applegate said. “It provides more resources overall to wealthier institutions and less to the institutions that are not as wealthy and who serve a large number of low- and middle-income students.”

“It is great that Illinois has some of the largest financial aid programs in the country targeting low-income students. But that doesn’t make up for everything,” Applegate said. “Equity, performance and improvement need to be fed into the way you reward institutions, just the way any successful business would do.”

Illinois had the third-largest net loss of degree-seeking undergraduate students in the U.S. despite these programs, according to the most recent data from the National Center for Education Statistics. One-third of college-bound students decided to attend schools in other states.

Pension costs, administration eat revenue

While the Illinois public universities that grew enrollment were punished most by the current funding formula, all universities have been forced to find money elsewhere to cover rising pension costs and administrative expenses.

An IBHE report found as State University Retirement System payments increased, universities historically raised tuition and fees to maintain operational budgets.

Analysis of Illinois’ budgets shows university pension contributions rose from $251 million in 2009, adjusted to today’s dollars, to over $2 billion in 2025 – an almost eight-fold increase. Funding for university operations declined by $542 million in real terms.

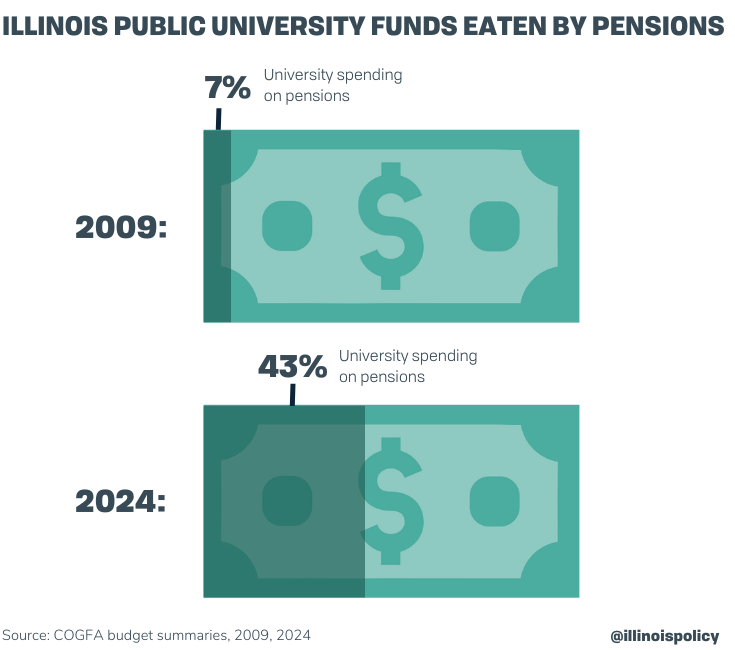

As a result, about 43 cents of every higher education dollar from state general funds went to pensions in 2024 instead of instructing students, compared to just over 7 cents in fiscal year 2009. That’s despite Illinois’ spending on higher education growing in real terms and as a proportion of the state budget, increasing from about 7% to nearly 9% of total state spending.

But even without considering the high costs of state pensions, Illinois still spends the third most in the nation on higher education per student.

Applegate said years of irresponsible promises and budgeting by lawmakers are largely to blame for the soaring public retirement costs in Illinois today, not the current pensioners who are seeking a secure retirement. All the same, the costs are having an impact on students.

“Illinois’ pension problem is not the current pensioners’ fault,” Applegate said. “This is a problem handed down to us by multiple administrations representing both parties and decades of politicians in Illinois acting irresponsibly.”

“I think lawmakers are being misleading when they say, ‘We’re putting all this into higher education,’ and almost half of it doesn’t go to the students,” Applegate said. “It’s going to support higher education pensions. It doesn’t educate one student. It doesn’t provide one piece of lab equipment.”

In addition to retirement costs, administrative costs have played a role. Illinois public universities spent more than 10% of their budgets on administrative expenses in 2024, according to IBHE. The state had 50% more administrators per student than the national average.

Applegate said the rise of non-faculty costs at Illinois’ public universities has been driven in part by increases in student support and technology services, expanding government requirements and the growth of development offices responsible for bringing in additional funds.

Higher education needs common-sense reforms

When students can’t get into their top choice, such as the University of Illinois, many leave the state instead of settling for a shrinking regional university. With future enrollment predicted to plummet by one-third in Illinois by 2041, attending a state school could become even more expensive.

The system is not aligned with the needs of today’s students or the state’s future workforce. Without reforms, the result will be more subsidies for institutions struggling with enrollment, fewer attractive choices for students and higher costs for taxpayers.

“I feel frustrated because I spent most of my life concerned about providing opportunities for success, helping those who could not otherwise get it launch into a good life,” Applegate said. “And while I think we’ve made some progress, I still think we’ve got a system that could be improved.”

“We need to take a closer look at the funding formula and focus on two things. One is a clear commitment to fair and equitable funding across the institutions, taking into account the types of students that they serve. And the second is transparency on outcomes with acknowledgement in the formula of improved enrollment and performance,” he said.

Fixing university funding means controlling future pension costs, reducing administration and changing the funding formula to reward enrollment and performance. Only that strategic, statewide approach will lower costs and keep young people in the state.

Illinois taxpayers fund over 12 years of public education, only to lose students after high school when they can’t afford higher education or attend college in other states. The children of Illinois will spend their productive years under-employed or as taxpaying members of other states’ communities.

That’s a losing investment that short-changes Illinois’ potential to put young people in lucrative careers close to the communities they grew up in.