When something sounds too good to be true, it often is…like the State School Board and the Kansas Department of Education claiming that skyrocketing proficiency levels are not related to the state dumbing down proficiency standards. Now, the Kansas Association of School Boards (KASB) is joining the chorus with a new video denying that proficiency standards were reduced.

Entitled “Why Kansas Adjusted Cut Scores,” the video attempts to convince parents that the State School Board didn’t reduce proficiency standards, but is merely adjusting previously misaligned standards to “give a fairer, more accurate picture.”

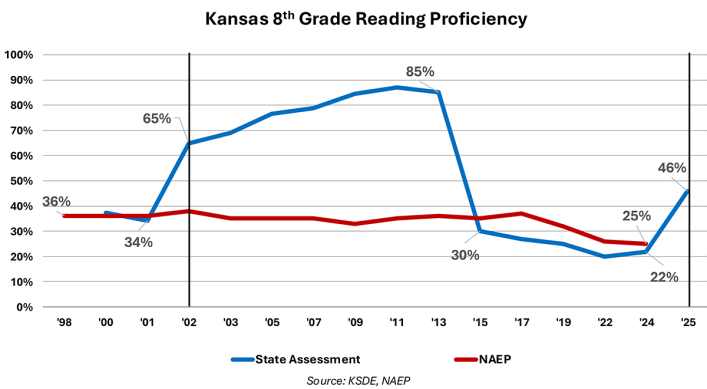

KASB and the State Board of Education want you to believe, for example, that eighth-grader reading proficiency jumped from just 22% last year to 46% without changing the proficiency standard. Their allegation that previous results were inaccurate doesn’t stand up to the facts.

It’s akin to not liking the results when you step on a bathroom scale, so you put a 25-pound barbell on the scale and reset it to show zero. Shazam! The scale now reflects that you are 25 pounds lighter, but you didn’t lose any weight.

The State Board of Education and Department of Education officials were embarrassed by having only a third of students proficient and more than 150,000 with a limited ability to read, so they adjusted the scale to show better results.

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) consistently showed about a third of 8th graders proficient in reading from 1998 through 2017, then dropping to about 25%. The NAEP test, also known as The Nation’s Report Card, is the gold standard of measuring proficiency in reading and math. State assessments showed very similar results in 2000 and 2001 (the blue line in the chart below).

Then, Kansas reduced proficiency standards as part of No Child Left Behind in 2002, and proficiency artificially jumped from 34% to 65% overnight. The increase wasn’t real, of course. The State Board of Education reduced the proficiency standard. It’s like having 90 to 100 qualifying for an A, then changing the standard for an A to 70 to 100.

The U.S. Dept of Education, which administers the NAEP test, said Kansas had low proficiency standards for many years, which is why state assessment results were so much higher than on the Nation’s Report Card. The proficiency level on the Kansas state assessment was often more than twice as high as on NAEP. Then in 2015, the State Board of Education went back to having high proficiency standards, and proficiency fell to 30%, and about the same as NAEP. The state assessment and NAEP showed very similar results from 2015 through 2024.

The pattern is consistent; state assessment results appear much better when the State Board of Education reduces the proficiency standard, and they look worse when the proficiency is reduced.

Smoke and mirrors obscure low student outcomes

According to KASB, the previous proficiency standards (also known as cut scores) sent “mixed messages” to parents because they “didn’t match up with the fact that kids were thriving, succeeding in college, courses, careers and beyond.”

Certainly, some students are thriving, but many are not, according to independent exams like NAEP and ACT.

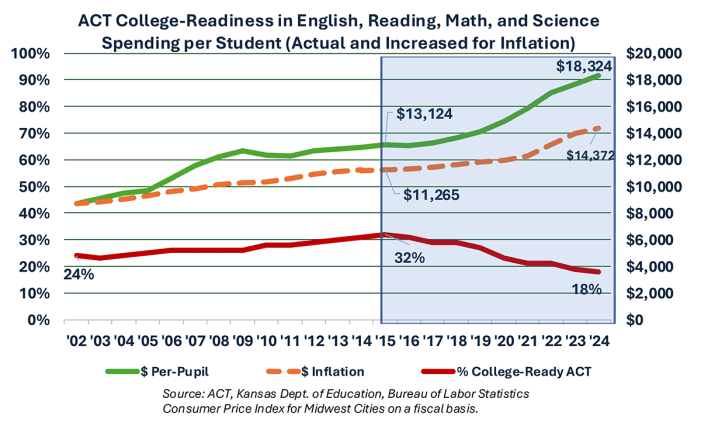

Kansas outcomes on the ACT exam have also been declining since 2015. College readiness in English, Reading, Math, and Science dropped from 32% to just 18% last year. ACT’s definition of college-ready – having a 75% chance or better of getting a C on an entry-level course – is not a high bar.

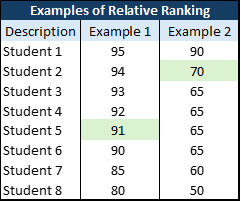

KASB also says, “Kansas set the bar so high you had to score in the nation’s top 25% just to be called proficient.” That apparent reference to the NAEP results is either a consciously false claim or they don’t understand how percentiles work.

The adjacent table shows two examples of the relative nature of percentiles, using a typical grading scale of 90-100 to get an “A”, 80-89 for a “B”, etc.. In the first example, Student #5 scored a 91 on a test, which ranks in the bottom half of the class even though it was an “A.” In the second example, student #2 ranks in the top 25% of the class with a score of 70.

The adjacent table shows two examples of the relative nature of percentiles, using a typical grading scale of 90-100 to get an “A”, 80-89 for a “B”, etc.. In the first example, Student #5 scored a 91 on a test, which ranks in the bottom half of the class even though it was an “A.” In the second example, student #2 ranks in the top 25% of the class with a score of 70.

Which student did better? The one in the top 25% of the class with a “C”, or the one who got an “A” and is in the bottom half? Obviously, the outcome is more important than the rank. Student #5 in Example 1 didn’t have to be in the top 25% to get an “A,” they had to score 90 or better.

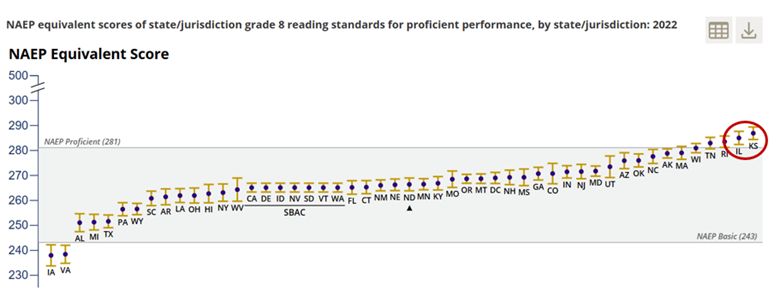

Now, let’s look at the NAEP standard for proficient in eighth-grade reading. The cut score is 281, and five states, including Kansas, had state proficiency standards in 2022 that equal or exceed 281. Students do not have to be in the top 25% to be considered proficient; they must have a state score that equates to 281 or higher on NAEP. Conversely, Oklahoma’s state score for proficient translates to Basic on NAEP; that score is in the top 25% of the nation, but it is not proficient.

Kansas didn’t have to be in the top 25% to be proficient on NAEP, as KASB claimed. It’s the score that matters, like getting at least a 90 to receive an “A.”

Most states have relatively low proficiency standards compared to NAEP; in the eighth-grade chart above, proficiency in Iowa and Virginia equates to Below Basic on NAEP. It’s because Iowa and Virginia have exceptionally low proficiency standards that their state assessment results reflect proficiency around 80%. Kids in those states are not smarter than in other states; they just have lower standards, like giving an “A” to scores above 60.

Lower proficiency standards on state assessments may make the state school board look better, but it’s a disservice to students. Students need REAL academic gains to be prepared for life after high school. That’s why the Legislature included performance goals in the Blueprint for Literacy passed in 2024, calling on the education system to improve from 33% proficient to 50% proficient by 2033. The State Board of Education and KSDE responded by reducing the proficiency standard to get there almost overnight.

State education officials are determined to have low proficiency standards, but they don’t have the final say. The Kansas Legislature has the legal authority to order the Department of Education to go back to the previous standards and the old assessment test, or to use an independent test like ACT Aspire for the state assessment.

The question each legislator must answer is whether they will intervene and require a return to high standards or do nothing, thereby condoning the new low standards and submitting to the will of KSDE and the State Board of Education.