It is a truth universally acknowledged that a young student in possession of a cell phone must be in want of a place to use it.

One prevailing theory behind the nation’s rapidly declining test scores places a large share of the blame squarely on the shrinking attention spans, short-term memories, and intellectual availability caused by cell phones and social media.

The theory holds water. Cell phones strongly affect adults’ attention spans (try to finish this article without looking at yours!) and have even stronger effects on children’s developing minds. Cell phone use strongly affects children’s sleep, depression and anxiety rates, impulse control ability, and their social and emotional health.

The physical classroom now reflects the dismal nature of a Zoom lecture: the teacher opines, cajoles, and enlightens before a sea of blank faces, vacuously looking down at their ChromeBooks or cell phones. One recent study found that students, on average, were on their phones during an entire quarter of the school day. Study feedback from teachers suggested that that was a very, very low estimate. The majority of high school teachers (72 percent) told Pew Research that distractions from cell phones are a major problem.

For many students, it’s not always a matter of self-discipline. Social media developers copy techniques from casinos and gambling websites to create psychological cravings that activate mechanisms in the brain that are similar to cocaine. Addictive and craving behavior can also worsen with repeated exposure to pornography. A high majority of teenagers have been regularly exposed to internet pornography, and while studies differ, it seems likely that more than half of America’s teenagers regularly use pornography. The social stakes connected to phones are high, too: students who log off social media or quit texting often risk losing their friends and their opportunities to expand their friendship circle. Research has found that peer pressure significantly predicts childhood social media addiction, and what could be a stronger weapon of peer pressure towards phone addiction than the truthful knowledge that, well, everyone is doing it?

The apps and sites accessed through cell phones are designed to malform children’s brains, and they often succeed. Even if a child (whether an elementary or high schooler) wants to pay attention in school, they may literally be unable to do so.

The role of a parent, or the role of those acting in loco parentis, like school administrators, includes the responsibility to protect children from their harmful impulses.

Yet parents are the ones to give children their first cell phone, and are often the loudest detractors when districts limit or blame phone use. The two most cited reasons for the gift are often the need to track a child’s location or the child’s need to fit in socially with their peers via texting or Instagram.

But some parents, full of conviction, have been fighting to change that culture. Parents around the country have been partnering with their communities and their local school districts to sign the Wait Till 8th pledge — a social pact that empowers parents to opt out of a child smartphone gift until 8th grade. Many parents have begun to buy their children (even high school students) smart watches or phones that can send limited calls and texts without addictive access to the Internet.

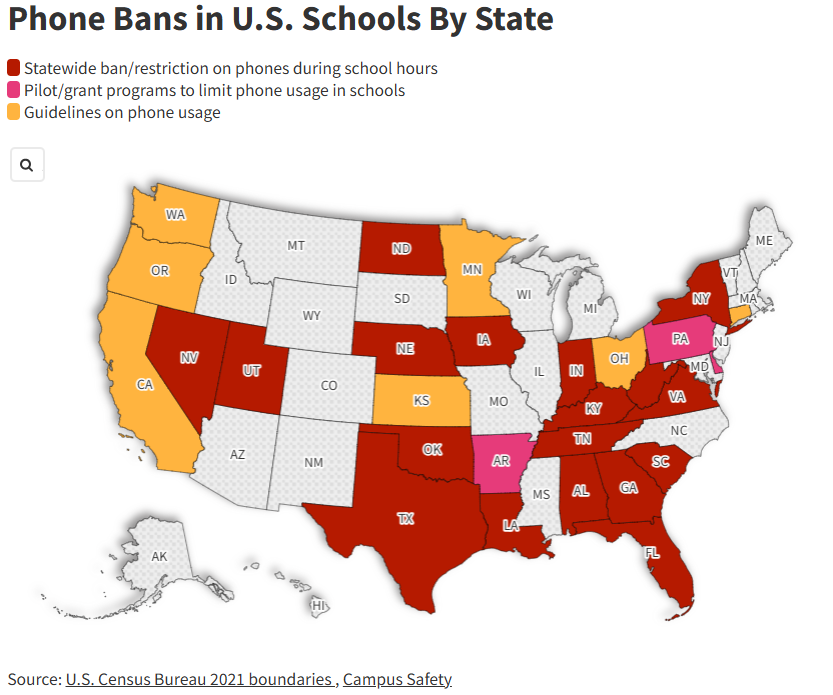

The social pact works best when school administrators share the vision. Around the country, many states have heavily limited or outright banned smart phone usage for students.

Minnesota hasn’t done so. Instead, Minnesota’s Department of Education has issued guidelines that districts must create their own cell phone policy. Many districts have done so, but only a few have fully outlawed the phones.

Full bell-to-bell phone policies can be implemented with the help of new technologies, like Yondr. The Yondr pouch is a magnetically sealed pouch, in which students put their phones during the first hour of the day. When students leave school, they scan their phone at a magnetic unlock “gate” that opens the pouch for them. Schools that have implemented the Yondr pouch have raved about the positive effects on school culture, and Yondr research suggests that academic performance goes up and behavior referrals go down in schools that use the technology.

Yondr and similar programs are popular programs that solve significant implementation problems associated with less expansive cell phone policies, but are expensive. The state of New York recently created a robust cell phone policy that included digitally locking pouches — for a cool $13.5 million price tag. Policymakers say that the investment in school culture and distraction-free classrooms is worth it. Arkansas recently approved a similar $7 million package.

The high cost of programs like Yondr might shed some light on why so many Minnesota districts have shied away from bell-to-bell bans on cell phones: they need strong fiscal support from the legislature. But strong leadership and funding from the legislature could make a dramatic difference in students’ lives.

In a way, it’s much easier for districts to successfully implement bell-to-bell cell phone bans than partial ones. If students know well the expectation that phones stay off and in their backpacks at all times, there is no nuance and no room for disproportionate discipline. But research suggests that the mere presence of a cell phone causes distraction, and students may feel an uncontrollable desire to peek. Fully funded bell-to-bell policies change this dynamic, allowing students the comfort of knowing where their phone is without the temptation. A student who carries their phone with them all day in a magnetically sealed pouch cannot check their inbox, even once.

Partial bans can work, but, as the name suggests, only partially. A student who is allowed to look at their phone during passing periods and lunch might be finishing up a message while they walk into class, and if they haven’t quite finished yet, perhaps they’ll feel compelled to finish during class. If a teacher (or substitute) is relaxed about phones in one class period, out the phones will come, and perhaps will not return in time for the next class period. This creates a spotty implementation and discipline process. It also removes the social pact element of a cell phone ban — if the whole school can access Instagram every fifty minutes, each child is socially rewarded by similarly giving their attention to the algorithm.

And, too, the periodic, continuous exposure to phones feeds the addictive impulses in students’ brains. There is no time for true digital rest and no space for deep learning.

Minnesota’s test scores are low, and its ranking in contrast with other states is also dropping. Innovation in the form of a fully funded cell phone ban could help free students from distractions and help them gain essential academic skills. Will we follow in the footsteps of New York, Arkansas, and Missouri, or will we wait until we are the laughingstock of the United States?