A recent research policy brief from the Sandra Day O’Connor Institute found that a strong majority of civics teachers said they had self-censored in class due to fear of pushback or controversy.

Civics teachers can face intense pushback from a variety of fronts. Students, parents, administrators, and policymakers can (and do) weigh in on the content of the classroom. Yet it appears that a nebulous culture of controversy creates more fear in civic teachers’ minds than concrete community pushback. 87.5 percent of civics teachers said that “fear of controversy” was a primary challenge to teaching civics, while 71.4 percent said that “fear of pushback from parents/community” was a primary challenge.

As the O’Connor Institute did not provide information about whether the teachers surveyed were largely in red or blue states, it is impossible to draw conclusions from this data about where cultures of fear are located. Nationally, administrators and teachers on both sides of the aisle, many of whom might find themselves in states unsympathetic to their political leanings, report increased levels of discomfort with civics education. A fear of controversy continues once students graduate and attend college: a recent study of Northwestern and University of Michigan students found that a high majority of students self-censor to appear more progressive. America’s lack of consensus on the answers to many topics raised in civics classrooms understandably turns up the pressure for educators.

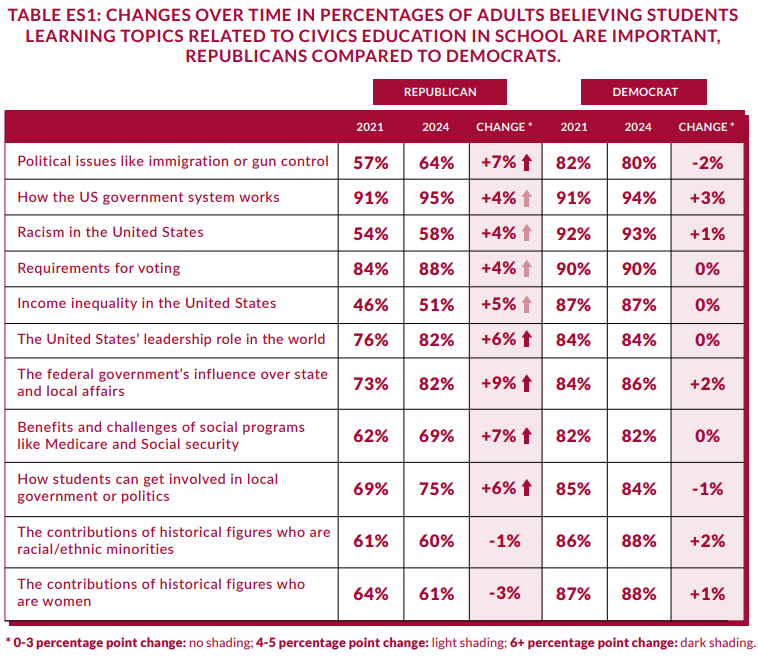

There is hope. A 2024 study from USC’s Center for Applied Research in Education found that bipartisan consensus on potential civics education topics is growing.

Aside from more abstract political concerns, civics teachers across the country suffer from two major roadblocks: unclear or discouraging instruction from administrators, and their own insufficient knowledge of American civics.

Administrative Ambiguity

In the O’Connor Institute’s survey, fewer than 15 percent of teachers said that their district provided clear and helpful guidance about what they are and are not allowed to teach in class.

Minnesota is no exception. The Fordham Institute studied Minnesota’s state standards in 2021 and awarded Minnesota’s civics standards a B-. Why the low score?

Compared to the state’s generally solid K–8 sequence, Minnesota’s high school standards are something of a disappointment. For example, one cosmic benchmark suggests that students “analyze how constitutionalism preserves fundamental societal values, protects freedoms and rights, promotes the general welfare, and responds to changing circumstances and beliefs by defining and limiting the powers of government” (9.1.2.3.1). Similarly, a benchmark on “foundational ideas” mentions “natural rights philosophy, social contract, civic virtue, popular sovereignty, constitutionalism, representative democracy, political factions, federalism and individual rights” (9.1.2.3.3). These are all essential concepts, but they cannot be treated seriously when they appear in such a laundry list. Furthermore, many otherwise well-crafted benchmarks lack depth. To wit, there are no examples whatsoever for the benchmarks covering the Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment—no famous or infamous Supreme Court cases or acts of Congress. Nor are there any examples of the “procedures involved in voting” or the “powers and operations” of local government in the benchmarks that address those topics.

In the 2023 legislative session, Minnesota lawmakers repealed the requirement that high school students take a heavily simplified version of the citizenship test given to applicants seeking American naturalization. The test consisted of 50 questions out of the 100 questions found on the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services Naturalization Test. The test was not required for graduation, could be taken as many times as needed to pass, and could be administered at any grade level or time seen fit by administrators.

Why the change? In the same legislative session, lawmakers required that high schoolers take a civics course in their junior or senior year. The change became effective beginning with the students entering 9th grade in the 2024-25 school year, to coincide with the intended implementation date of the 2021 Academic Standards in Social Studies in 2026-27. As an entire course is now focused on civics, the logic goes, the civics test is no longer needed.

My colleague Catrin Wigfall has argued that the civics test is deeply relevant to Minnesota’s students, citing nationally declining knowledge rates of foundational civics content and ongoing deep concern regarding the proposed content of Minnesota’s civics education.

Unprepared civics teachers

Civics teachers may also self-censor due to a lack of confidence in the material they are teaching.

In a 2013 study, researcher Wayne Journell studied 121 preservice social studies teachers. Only 25 percent of secondary and just five percent of middle-grade candidates could name both U.S. senators from their state. Fewer than a fourth of the future educators could identify the chief justice of the Supreme Court. The candidates were shocked and embarrassed by their lack of knowledge. While some chalked their inadequacy up to a type of intellectual sloth (for instance, watching a movie is much easier than reading the news carefully) others blamed their intellectual inheritance. If dinner-table conversations, backyard barbeques, and their own schooling experience treated civics content as superfluous, there were no clear paths or incentives to study widely on their own.

It’s very possible that the uninformed civics teachers of today were the uneducated civics students of yesterday. Civic knowledge has been dropping in the United States. For example, a recent Chamber of Commerce survey found that

70% of Americans fail a basic civic literacy quiz on topics like the three branches of government, the number of Supreme Court justices, and other basic functions of our democracy. Just half were able to correctly name the branch of government where bills become laws. While two thirds of Americans say they studied civics in high school, just 25% say they are “very confident” they could explain how our system of government works.

As more would-be civics teachers move through educational systems staffed by educators who possess loose grasps themselves on the facts, the problem compounds. The O’Connor Institute pointed towards a 2019 RAND survey of 223 high school civics teachers, which revealed that

only 32 percent rated factual knowledge—such as the names of the 50 states or key historical dates—as “absolutely essential,” down from an already low 36 percent in 2010. Similarly, just 53 percent cited understanding of government structure and constitutional principles as essential, versus 64 percent in 2010.

As fact-based civics education has become either inaccessible or unpopular among civics educators, pedagogy has evolved to emphasize student abilities over student knowledge. After all, it’s easy enough for a student to search the name of a senator from their phone. It’s much more difficult for them to learn the type of political involvement and conflict resolution skills that are essential for their contribution to democracy. Within this school of thought, the ideal civics classroom would resemble a Braver Angels event, with a bit more homework attached.

The Brookings Institute’s Rebecca Winthrop argued that civics education must include both student abilities and student knowledge — and a large dose of American social values. She writes that

This focus on mastering academic subjects through a teaching and learning approach that develops 21st-century skills is important but brings with it a worldview that focuses on the development of the individual child to the exclusion of the political. After all, one could argue that the leaders of the terrorist organization ISIS display excellence in key 21st-century skills such as collaboration, creativity, confidence, and navigating the digital world. Their ability to work together to bring in new recruits, largely through on-line strategies, and pull off terrorist attacks with relatively limited resources takes a great deal of ingenuity, teamwork, perseverance, and problem solving. Of course, the goals of Islamic extremists and their methods of inflicting violence on civilians are morally unacceptable in almost any corner of the globe, but creative innovation they have in abundance. What the 21st-century skills movement is missing is an explicit focus on social values. Schools always impart values, whether intentionally or not….The very nature of developing and sustaining a social norm means that a shared or common experience across all schools is needed.

Winthrop argues that the “powerful push for 21st-century skills with the less well-resourced but equally important movement for civic learning” should be unified in order to give students the best of all worlds: the tripartite combination of values, knowledge, and skills.

As a quality civics education is an essential part of the continuation of American democracy, more research should be done to identify the needs of civics teachers and supply them with resources. My colleague Catrin Wigfall identified resources for Minnesota’s teachers and school boards (who select curricula) to consider that will elevate civics education in the classroom. Parents and community members can serve on local district advisory committees to advocate for rigorous civics curricula.

While a focused civics course is a step in the right direction, lawmakers should consider revisiting the soon-to-be-implemented social studies and civics standards (which were, among other labels, called “absolutely useless” by national expert Dr. Wilfred Mcclay) to ensure their classroom efficacy, and reinstating the civics test requirement. The brave men and women who pursue American naturalization overwhelmingly pass the naturalization test (95.7 percent) — why can’t our students be asked to correctly answer just half of the questions that they must?

All Minnesotans can benefit themselves, the students in their lives, and Minnesota’s civic discourse as a whole by staying regularly informed, participating in local politics, and perhaps engaging in regular across-the-aisle discussions.