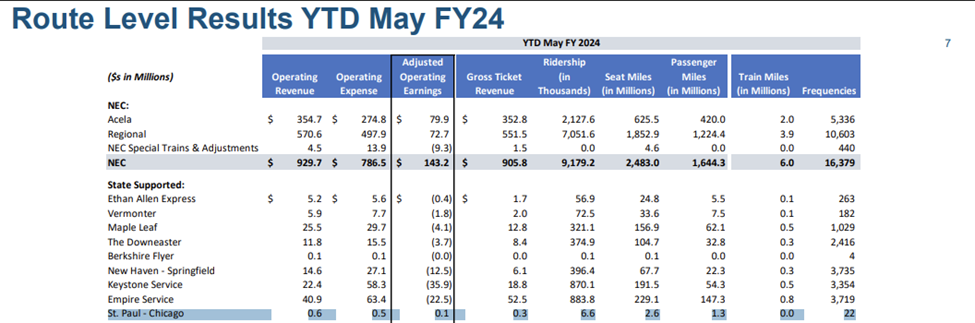

In the first eleven days of its operation in May 2024, Amtrak’s Borealis service between St. Paul and Chicago generated a “profit” of $100,000 which excited a few local people.

In fact, as I and others noted shortly afterwards, this was based on a basic misreading of Amtrak’s reports. True, subtracting “Operating Expense” from “Operating Revenue” did leave you with $100,000 left over, but only half of this Operating Revenue — $300,000 — came from “Gross Ticket Revenue.” The rest — $300,000 — came from “state subsidies to the train,” as Adam Platt wrote for Twin Cities Business. Without these subsidies, the Borealis would have lost $200,000 in its first eleven days.

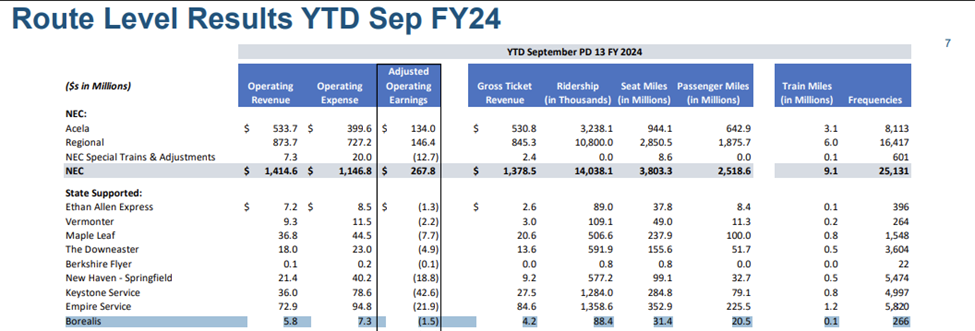

In no month since then has the sum “Operating Revenue” minus “Operating Expense” yielded a positive sum for the Borealis: it has lost money even on that generous misreading of Amtrak’s numbers.

Looking at the actual numbers, the story is even grimmer. By September 2024, when Amtrak closed its books for the year, the total loss (Gross Ticket Revenue minus Operating Expense) totaled $3.1 million and the state subsidies (Operating Revenue minus Gross Ticket Revenue) totaled $1.6 million, or $18.10 per ride.

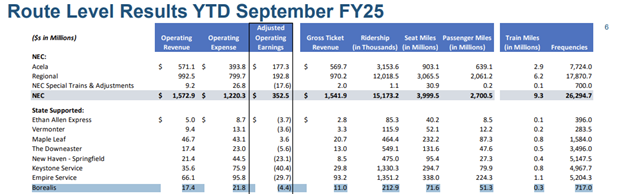

These numbers have deteriorated further over the subsequent year. Amtrak’s numbers are now out for the year up to September 2025. They show that the total loss (Gross Ticket Revenue minus Operating Expense) totaled $10.8 million and the state subsidies (Operating Revenue minus Gross Ticket Revenue) totaled $6.4 million or $30.06 per ride. This is 66% up from the previous year.

Needless to say, none of July 2024’s credulous commentators are crowing any longer about the Borealis turning a “pretty profit.” The boosting is now based on ridership numbers which have, it is true, exceeded initial projections of 124,000 annual riders with 212,900 in the year to September 2025. But, with fares starting at $41 each way for adults which implies an average subsidy of 42%, we perhaps shouldn’t be surprised that demand is strong; one’s demand tends to increase when someone else is paying for 42% of it.

How is the service performing financially relative to forecasts? This is an important question because, while there is a federal grant provided to cover 90% of the first-year operating costs, “over time the states [of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Illinois] became increasingly responsible for deficits,” Platt noted. And these deficits are rising.