By: Vance Ginn, Ph.D. and Joseph Johns

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Property taxes are a significant burden on Floridians as they fund local government spending. Collections now exceed $55 billion annually, with assessments growing far faster than population growth and inflation over the last two decades. Even with Florida’s “Save Our Homes” assessment cap, local government spending has surged and pushed local officials to raise property taxes, reducing housing affordability for many families, employers, and entrepreneurs. Governor Ron DeSantis has proposed both short-term relief, such as $1,000 rebates for homesteaded properties, and a longer-term goal of constitutional reform to reduce or eliminate property taxes. Lawmakers and policy groups are also advancing ideas ranging from expanded exemptions to transfer taxes, sales tax swaps, and surplus-driven buydowns. According to a September 2025 JMI poll, 72% of registered voters in Florida want some type of property tax reform, whether through a total elimination or limitations, underscoring the need for a careful approach.

This paper reviews the economic and fiscal implications of Florida’s property tax system and outlines the leading reform options under consideration. Drawing on lessons from other states, including Texas, where overspending has undermined property tax relief efforts, and Wyoming, which has considered replacing school property taxes with a broad-based sales tax, it highlights both the opportunities and the risks Florida faces.

Key themes include:

- The burden of property taxes: They act like a recurring wealth tax, penalizing homeownership, raising rents, and discouraging investment. Compared with regional peers like Alabama and Tennessee, Florida’s effective property tax rates are higher, despite the state’s overall strong tax competitiveness.

- The real driver: government spending. Without strict spending limits of a maximum growth rate based on population growth plus inflation, any tax relief risks being temporary. Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR) offers a model for sustainable restraint.

- Florida’s recently convened House Select Committee on property taxes shows that nearly half ($13.7B of $29.5B) of school funding across the state comes from property taxes.

- Options on the table:

- Incremental relief, such as homestead exemptions, appraisal caps, or levy caps, can provide short-term breathing room but risk shifting burdens.

- Surplus-driven buydowns can gradually compress millage rates when paired with disciplined local spending.

- Sales tax swaps could shift school property taxes to a consumption-based system, but require careful design to avoid tax pyramiding. They should focus on reducing the overall tax burden by spending less or collecting less revenue, rather than pursuing a revenue-neutral redesign.

- Hybrid approaches may combine these tools with local flexibility under strict guardrails.

- Eliminating school millages could provide meaningful property tax liability relief, but would require strict fiscal discipline, combined with a diversion of sales tax revenue to local schools.

- Transfer taxes on property sales, which have been discussed in the House, offer revenue potential but raise questions of volatility and fairness.

Rising housing costs, rapid population growth, and political momentum create a rare opportunity to address one of the most distortionary taxes in the system. This paper does not advocate a single path but provides a framework for evaluating reforms with evidence, comparisons, and clear rules of the game. The goal is straightforward: to restore true homeownership, enhance transparency, and ensure Florida’s tax system supports—not hinders—economic opportunity and prosperity for generations to come while funding limited government.

Introduction – Florida’s Property Tax Challenge

Florida’s reputation as a low-tax state is well-earned: it has no personal income tax, a business-friendly climate, and a $1.7 trillion economy that now ranks fourth in the United States and continues to outperform most regions. Yet beneath this reputation lies a growing problem—an overreliance on local property taxes, which now make up the largest single source of local government revenue, totaling $55 billion annually. Unlike sales or income taxes, property taxes function as a perpetual claim on ownership of property. Even after a mortgage is paid off, Floridians must continue to send checks to the government—or risk losing their homes. For renters, the burden is just as real, as landlords typically pass through 50% to 85% of their property tax bills in the form of higher rents. Businesses also face these costs, which can discourage investment in new facilities and equipment, thus slowing economic activity, reducing employment, and raising poverty.

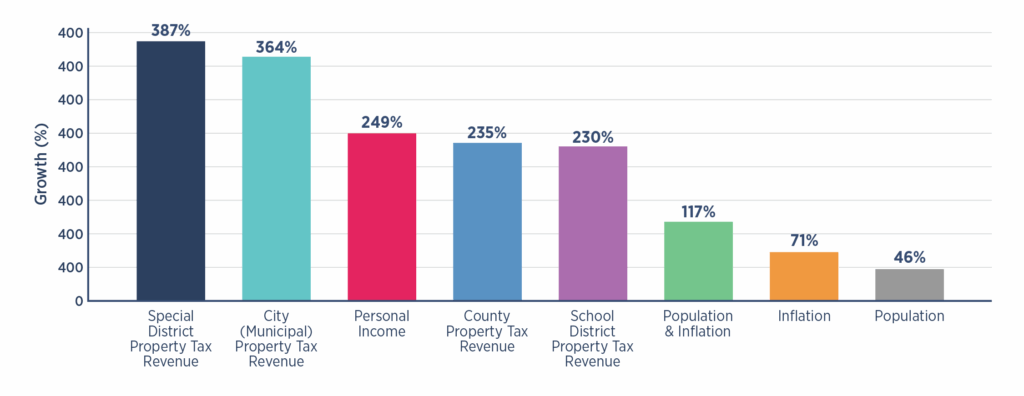

Over the past two decades, the burden has steadily increased. According to the Florida Department of Revenue, assessed property values statewide increased by more than 370% between 2000 and 2024, while combined population and inflation grew by about 116%. Figure I below compares the growth rate of total revenue collections of four unique levels of local government between 2000 and 2024. The figure also compares total revenue growth to the growth in personal income, inflation and population growth as a relevant benchmark to provide further context to the growth of total property tax revenues compared to standard economic growth measures.

Figure I: Growth in Florida Property Tax Revenues vs. Economic Benchmarks (2000–2024)

Even with the “Save Our Homes” cap limiting annual increases for homesteaded property appraisals to the lesser of 3% or inflation, local governments have relied on new construction, rising valuations, and debt to push revenues ever higher. When compared with regional peers, Florida’s property tax burden looks less competitive than its overall tax structure might suggest. According to the Tax Foundation, Florida ranks 21st among states on property tax competitiveness, with effective rates averaging 0.74% of home value—nearly double Alabama’s 0.36% and well above Tennessee’s 0.49%. Only Texas, at 1.36%, bears a heavier effective burden among major regional competitors.

Rising collections are feeding into Florida’s housing affordability crisis, where families in Miami-Dade, Orlando, and Tampa often spend more than 30% of their income on housing, and renters in particular face record-high costs. Local officials argue that property tax revenue is essential for funding schools, public safety, and infrastructure. Yet critics note that government spending growth continues to outpace the ability of taxpayers to pay, with little accountability for efficiency or transparency. Governor Ron DeSantis has tapped into this frustration, proposing both rebates averaging $1,000 per homesteaded property and a longer-term constitutional amendment to eliminate property taxes. Legislators are weighing additional proposals—from levy caps and expanded homestead exemptions to complete elimination through sales tax swaps or surplus-driven buydowns.

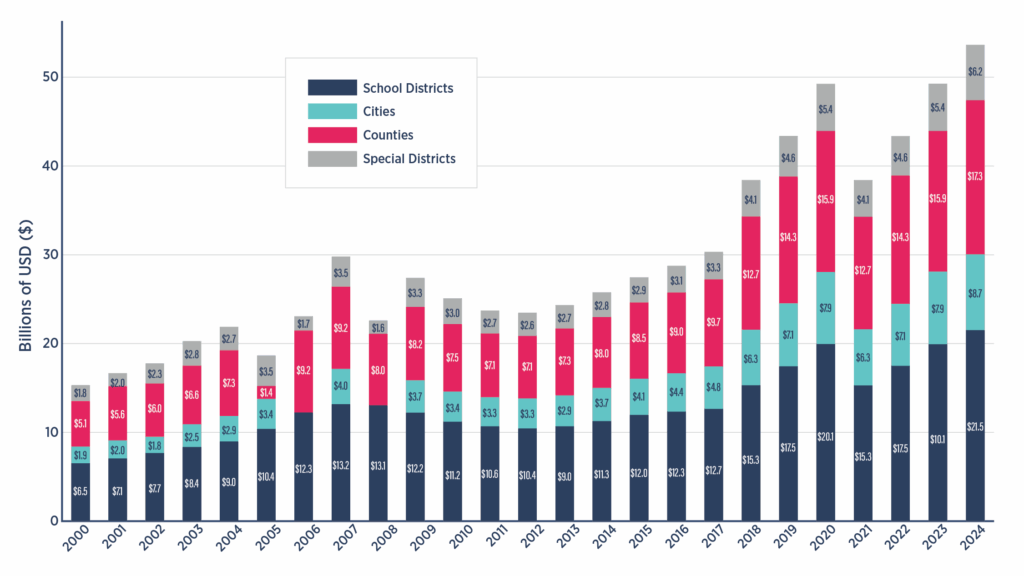

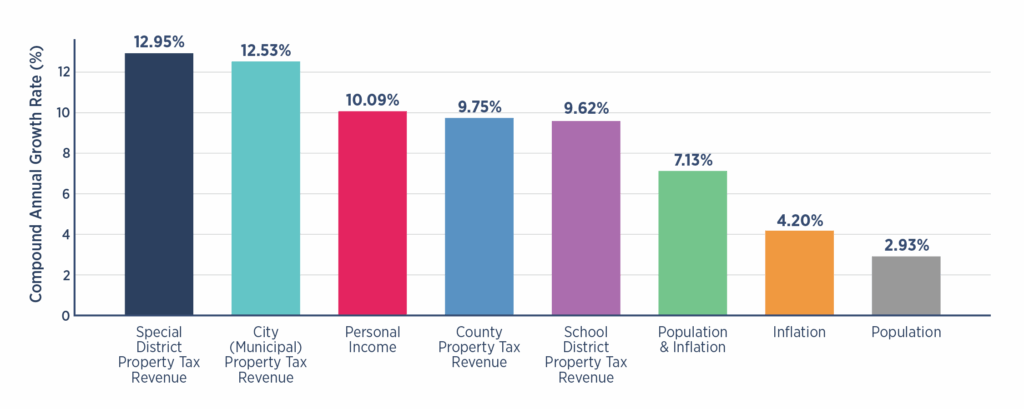

Figure II displays Florida’s total property tax levies between 2000 and 2024. Meanwhile, Figure III displays the compound average annual growth rate of each local government and key economic indicators, as shown in Figure I above.

Figure II: Total Property Tax Levies by Level of Local Government

Figure III: Compound Average Annual Growth Rate of Local Government Property Tax Revenue (2000 – 2024)

Florida now faces a pivotal question: What is the most effective path to reduce or eliminate property taxes while maintaining essential services and long-term fiscal stability? This paper examines the economic and budgetary costs of Florida’s property tax system, reviews the primary reform options under consideration, and compares Florida’s situation with that of neighboring states and national trends. The aim is to provide policymakers with the evidence, comparisons, and tools needed to make informed decisions.

The Economic and Budgetary Costs of Property Taxes in Florida

Property taxes are often defended as a “stable” source of revenue, but stability for government appropriators comes at the expense of instability for families, renters, and employers. Property taxes function like a recurring wealth or unrealized capital gains tax, a perpetual claim on property that families must pay even after their mortgages are paid off. Miss a payment, and the government can seize the home. This creates a system where Floridians never truly own their homes.

Research from the Philadelphia Federal Reserve shows that lower-valued homes are overassessed, relative to higher-valued homes. This drives up the tax burden for lower-income Florida residents who own smaller, lower-valued homes. Economists refer to this as a regressive property tax structure, which harms the very Floridians who are most in need of property tax relief. Owners of inexpensive homes often face effective property tax rates that are at least 50% higher than those of more real-estate-wealthy homeowners. Further research from Harvard Law School’s Journal on Legislation finds that property tax regressivity is not a statistical fluke resulting from higher assessed values across the board. Instead, the property tax is regressive due to a series of conscious, intentional policy decisions that fail to exert sufficient oversight of local assessment practices. Multiple states’ property tax assessments have consistently demonstrated a regressivity bias levied against lower-income households over several years and across various taxing jurisdictions. One possible solution proposed by the authors involves centralizing property tax assessments in larger municipalities, such as counties. The data in this report support this suggestion as potentially helpful, as smaller Florida municipalities show the highest growth in total property tax levies between 2000 and 2024.

For many households, property taxes are the second-largest monthly housing expense after the mortgage itself. In Florida, the average effective property tax rate is 0.74% of home value, according to the Tax Foundation. On a $384,900 home—the statewide median as of July 2025—this translates to an annual tax bill of about $5,400, after controlling for Florida’s dual-tiered property tax structure. Liabilities can rise each year as assessments increase, placing further strain on Florida homeowners. For retirees and families on fixed incomes, this burden can make the difference between stability and financial hardship, such as foreclosure. By comparison, Tennessee homeowners face a rate of just 0.49%, or about $1,700 annually, on the same $350,000 home. Alabama households pay even less—0.36%, or about $1,250 annually. Florida’s effective rate is lower than in Texas, where homeowners pay 1.36% (over $4,700 annually on the same home), but Texas is considering ways to reduce this heavy burden. Florida risks falling behind in competitiveness if it does not confront its own growing burden.

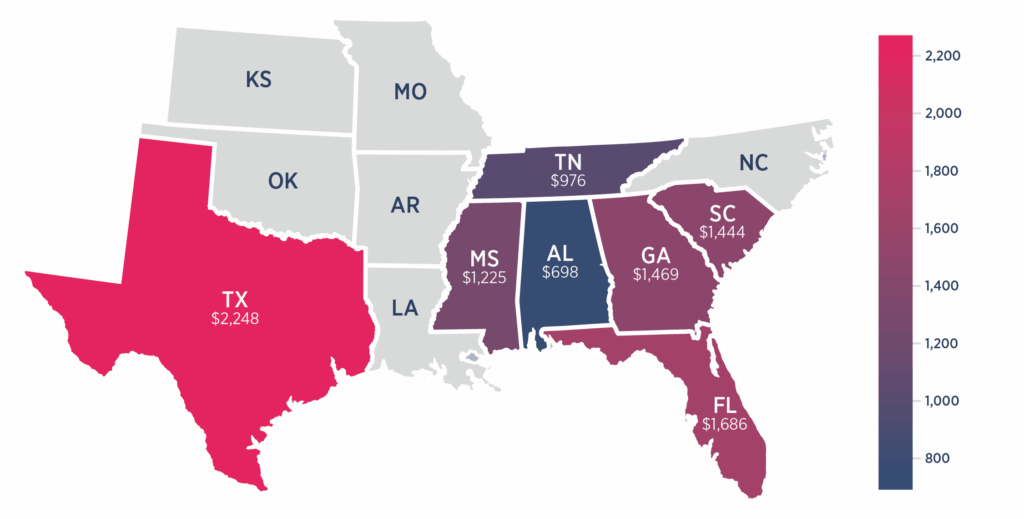

Renters, who comprise more than a third of Florida households, face indirect but significant financial burdens. Landlords in commercially zoned, highly dense municipalities typically pass through 50% to 85% of their property tax bills in the form of higher rent, as found by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. In high-cost metro areas like Miami-Dade, Orlando, and Tampa, property taxes can account for 20% or more of the monthly rent. This compounds Florida’s housing affordability crisis, where the median gross rent now exceeds $1,800, and more than half of renters spend over 30% of their income on housing. According to state-level data from Zillow’s Observed Rent Index, Florida’s average monthly rent for a 2-bedroom apartment was $2,500 in 2024. Figure IV below shows that relative to six other states in the same region as Florida, the Sunshine State has the highest average annual rent for all rental homes.

Figure IV: Difference in 2-Bedroom Average Rent vs. Florida (2024)

Employers also face property taxes as a fixed cost, whether on land, warehouses, or equipment. In capital-intensive sectors such as agriculture, logistics, and manufacturing, these taxes discourage investment in machinery and expansion, or risk being passed along to consumers and workers in the form of higher costs. By contrast, a consumption-based tax, such as a sales tax, is paid only when sales occur, making it more responsive to economic cycles. Property taxes, in contrast, must be paid regardless of profitability, which is particularly damaging during downturns.

Another cost of property taxes is their lack of visibility for many people. Unlike sales taxes, which are typically displayed on receipts, property taxes are often included in mortgage escrow accounts or rent payments. Homeowners may only see the total once a year, while renters may not see it at all. This lack of transparency weakens taxpayer awareness of the link between government spending and their tax burden, making it easier for local governments to grow unchecked. Economists measure tax progressivity and regressivity using tools like the Suits Index. According to the Texas Comptroller’s 2025 analysis, the Suits Index for school district property taxes was –0.068, compared with –0.252 for sales and use taxes. While this suggests that property taxes are less regressive than sales taxes when measured against annual income, such studies overlook “lock-in” effects (homeowners are trapped in their properties because moving means higher taxes, which keeps new homebuyers out) and “push-out” effects (families are forced to sell when taxes outpace income growth). These dynamics make property taxes highly regressive; likely more regressive than sales taxes. This is because sales taxes do not often deter people from buying something, nor prevent them from owning it after payment has been made.

Unsustainable Growth of Property Tax Collections in Florida

While property taxes are burdensome to households, renters, and employers, their rapid growth is the deeper problem. Florida’s property tax collections have risen far faster than the economy, population, or inflation can justify—placing an unsustainable strain on taxpayers. Florida’s House Select Committee provides evidence that highlights constitutional provisions, such as the Save Our Homes cap, which shifts burdens onto businesses and rental properties, exacerbating inequities. Since this cap shifts the goalposts for what type of property can be taxed, it encourages local governments to become opportunistic with their revenue-generating strategies. This creates more risk for households and businesses, as they seek a stable, predictable, and reliable level of public services delivered at the lowest possible price. Florida counties rely heavily on property taxes, accounting for 26.7% of statewide revenues, which fund public safety, health, elections, and infrastructure. Expenditures grew 20% between 2021 and 24, with public safety leading the increase.

Between 2000 and 2024, the assessed value of all property in Florida grew by 341%, according to the Florida Department of Revenue. Over the same period, Florida’s population grew by 45.6% and inflation rose by 70.7%, resulting in a combined simple increase of 116.3%. Even accounting for compounding, population plus inflation growth falls far short of the more than tripling in assessed values. This divergence illustrates how local governments have leveraged rising property valuations to increase collections, despite constitutional protections such as the “Save Our Homes” annual cap on homestead assessment increases. Collections have consistently outpaced taxpayers’ ability to pay, driving housing costs higher and undermining affordability.

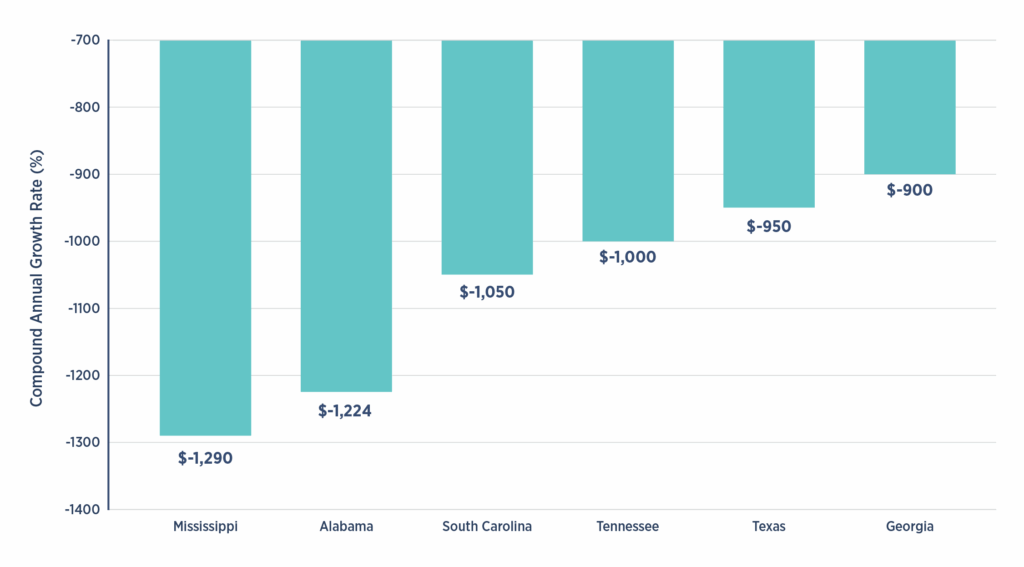

When compared nationally, Florida’s per-capita property tax collections—$1,686 in FY 2022—are higher than most southeastern peers but lower than the national average of $2,131. Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee all collect less per capita, while Texas collects far more at over $2,200. Yet Florida’s substantial population and economic growth mean its property tax system is playing a larger role in affordability challenges than in slower-growth neighbors. When compared to nearby states, Table I and Figure V show that Florida’s property tax burden is higher than most other Southeastern states.

Table I. Florida and Neighboring States – Property Tax Comparison

| State | Property Tax Subindex Rank (2025) | Collections per Capita (2022) | Effective Tax Rate (% of Home Value) (2023) |

| Alabama | 16 | $698 | 0.36% |

| Florida | 21 | $1,686 | 0.74% |

| Mississippi | 29 | $1,225 | 0.58% |

| Georgia | 32 | $1,469 | 0.77% |

| Tennessee | 37 | $976 | 0.49% |

| Texas | 40 | $2,248 | 1.36% |

| South Carolina | 42 | $1,444 | 0.47% |

Figure V: Comparison of Florida’s Per Capita Property Tax Burdens, FY 2022

Florida ranks closer to Texas than to its immediate neighbors. This matters because, unlike other states, Texas and Florida do not levy a personal income tax; instead, they rely heavily on sales taxes. Without reform, Florida risks undermining the very competitiveness advantage that draws families and businesses to the state. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, property taxes account for about 36% of Florida’s state and local tax revenues—above the national average of 32%. Local governments are the primary drivers, as property taxes remain their largest single source of revenue, exceeding $55 billion annually. This dependence creates pressure for ever-higher collections, especially as local budgets expand. Once governments adjust to higher revenues, spending tends to ratchet upward, making reductions politically and fiscally challenging.

The unsustainable growth of collections cannot be separated from spending trends. Research from Americans for Tax Reform’s Sustainable Budget Project reveals that state and local spending growth nationwide consistently outpaces population growth plus inflation. Florida is no exception. Without hard caps, surpluses are absorbed into higher baselines, leaving little room for permanent tax relief. The lesson from other states is clear: slowing or eliminating property taxes requires constitutional or statutory limits that tie annual spending growth to the sum of population growth and inflation. Without such limits, even well-intentioned reforms risk being undone by unchecked budget growth.

If left unchecked, Florida’s property tax growth could worsen affordability and erode the state’s economic competitiveness. High-growth counties such as Miami-Dade, Hillsborough, and Orange already rely on property taxes for more than a third of their budgets. Without structural reform, future increases could price more families out of homeownership and deter businesses from expanding in the state. By contrast, states that have paired strict spending caps with revenue limitations—such as Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR)—have demonstrated that it is possible to align government growth with the average taxpayer’s ability to pay for spending. Florida lacks such a constitutional mechanism, leaving homeowners vulnerable to escalating property tax bills driven by rising valuations.

Reform Options for Florida

Florida policymakers have several potential pathways to ease and possibly even eliminate property taxes. Each option comes with its advantages and drawbacks, and no single strategy will work in the same way everywhere. Below, we examine the major approaches under discussion and highlight lessons from other states. The key is reining in spending at the state and local levels to fund only limited government, thereby helping reduce the burden on taxpayers to finance government spending.

Incremental Relief Tools

Expanded homestead exemptions, targeted rebates, appraisal caps, and levy caps are the most common reforms considered in state legislatures.

- Pros:

- Provides immediate relief to homeowners.

- Levy caps can slow the growth of property tax bills.

- Rebates are flexible and can be directed toward the households that bear the greatest burden.

- Cons:

- Shifts the burden onto renters and employers who do not qualify for exemptions.

- Temporary relief, not structural reform; collections often continue to grow.

- Texas repeatedly raised homestead exemptions, yet overall property tax burdens continued to climb due to unchecked local spending.

Florida could adopt these tools as short-term relief, but without discipline on the spending side, they risk being little more than political stopgaps. Obscure rate adjustments and new fees often undo property tax relief. To prevent this, reforms could require governments to adopt the “truth in taxation” standard. Whenever property valuations rise, millage rates must fall to keep the total levy flat unless voters approve an increase. Florida already practices a version of this through its rollback rate system, but strengthening it with constitutional backing would ensure consistency across jurisdictions.

Surplus-Driven Buydowns

The surplus-driven buydown approach, most evident partially in Texas, dedicates state surpluses to compress school property tax rates until they are phased out. This includes the state’s restraint on spending and using surpluses to reduce school district property tax rates. This also includes local spending restraint, with local surpluses going to reduce property tax rates. This process would continue every budget cycle until property taxes are eliminated.

- Pros:

- Gradual, predictable process that avoids sudden shocks to budgets.

- Allows taxpayers to see consistent annual reductions.

- Encourages fiscal discipline by requiring surpluses from restrained spending.

- Cons:

- Dependent on continued revenue increases and political will to prioritize tax relief over new spending.

- Without firm local limits, reductions can be erased if counties or cities raise their own levies.

- Slow process—can take a decade or longer to eliminate if desired.

For Florida, which benefits from substantial tourism-driven revenue, a buydown strategy could be viable if lawmakers commit to constitutional spending caps.

Tax Swap

A tax swap is a direct swap of school property taxes for a statewide sales tax on final goods and services. Florida already relies heavily on sales taxes, making this option administratively feasible. Covering Florida’s $13.6 billion in school property taxes (FY 2025–26) would require raising the state sales tax rate by approximately 2.1 percentage points, assuming a broad sales tax base. However, many counties already impose local surtaxes of 0.5% to 2%, thereby limiting the available room before reaching statutory caps. This makes a full replacement challenging without either broadening the base or enacting a hybrid model.

- Pros:

- Transparent: taxpayers see the tax on every receipt.

- Broad sales tax base captures contributions from nonresidents and tourists.

- Ensures stable funding for schools, since the state already manages education finance.

- Cons:

- Regressive when measured annually, though less so over a lifetime, and may not lower the overall tax burden.

- Politically sensitive, as it would require raising the statewide sales tax rate to 8.1% from its current 6%, Must exclude business-to-business transactions to avoid harmful tax pyramiding, like with a value-added tax (VAT).

- 8 counties with the highest local option sales tax rate of 2.5% would have all of their sales tax base, minus exclusion, taxed at 10.6%. This would exceed Louisiana’s 10.11% combined state and local sales tax rate as of June 2025.

Florida could consider a partial swap that targets school property taxes first, covering about half of collections, while leaving local governments to manage the rest under spending limits. Using data from the Florida Department of Revenue and the Florida Department of Education, we recalculated the property tax and sales tax swap figures that were applied to Texas. This is possible due to the similarity of Texas and Florida’s state and local finance structures. Both states forgo a statewide sales tax, instead relying on sales and property taxes to generate the majority of their revenue. In 2023, total ad valorem property tax collections across Florida amounted to $50.9 billion, with approximately $13.3 billion (26 percent) attributable to school district maintenance and operations (M&O) levies under the Required Local Effort and discretionary millages. The statewide average M&O millage was 3.937 mills, applied to a taxable school property value of roughly $3.37 trillion.

Applying a migration model for tax reform changes, as was used with a recent analysis for Texas, a repeal of Florida’s school M&O property taxes and corresponding replacement through the sales tax would generate a net in-migration to Florida on the order of hundreds of thousands of new residents annually, producing an estimated $45 to $50 billion in additional private gross state product (GSP). This expansion in both population and economic activity broadens the sales tax base, such that the implied dynamic total state and local sales tax rate required to replace school M&O property taxes entirely falls to about 6.58%—a modest increase from today’s combined 7.02% state and local sales tax rate. These results suggest that Florida could feasibly fund the repeal of school M&O property taxes through sales tax reform, while simultaneously benefiting from pro-growth migration and investment effects.

Local Flexibility and Compacts

Some proposals allow counties and municipalities to diversify revenue sources, for example, through local sales taxes or tourism-related levies, while living under strict caps. States may experiment with the idea of “local compacts” to harmonize tax bases across jurisdictions.

- Pros:

- Tailors solutions to local economies (e.g., Florida’s tourism-heavy regions).

- Encourages efficiency through shared services and competition among jurisdictions.

- Gives voters direct accountability at the local level.

- Cons:

- The risk of new taxes being layered on top of property taxes unless guardrails are in place is significant, as introducing new taxes without eliminating others is bad policy.

- Some rural areas with limited tax bases could struggle to replace property tax revenue entirely. (Half of Florida counties are designated “fiscally constrained”.)

- Requires strong state oversight to ensure overall burdens do not increase.

This approach may work well in Florida.

Transfer Taxes on Property Sales

A tax on property transfers at the point of sale is another option some Florida legislators are considering.

- Pros:

- Reduces annual costs for long-term homeowners who stay in their homes.

- Revenue is directly tied to property transactions, making it visible at the time of closing.

- Could be paired with other reforms to accelerate the phaseout of property taxes.

- Cons:

- Highly volatile—collections drop during recessions or housing market downturns.

- Discourages mobility by making it more costly to move.

- Unreliable as a stable long-term revenue source for schools or local services.

While attractive as a short-term offset, caution should be exercised against overreliance on transfer taxes due to their instability.

Hybrid Approaches

A blend of reforms may be the most practical way forward. Florida could:

- Begin with stronger state and local spending limits based on a maximum growth rate of population plus inflation, and property tax revenue caps at 0% without an election to provide immediate relief from excessively growing property taxes.

- Dedicate state surpluses to compress school property taxes.

- Introduce a limited sales tax swap to replace a major portion of property tax revenue.

- Allow local governments narrow flexibility under strict spending limits, with surpluses from other revenues dedicated to reducing their property taxes.

This combination strikes a balance between near-term relief and long-term structural reform, ensuring that Florida taxpayers see progress while protecting essential services.

Safeguards and Guardrails

No property tax reform—whether incremental or sweeping—will succeed without strict safeguards to keep government spending and taxation in check. Florida’s challenge is not just to restructure revenue but to ensure reforms are lasting and not undermined over time. History shows that without firm constitutional protections, short-term relief often evaporates as new spending commitments emerge. Schleicher warns reforms must avoid worsening NIMBYism and segregation. Pairing assessment reform with zoning modernization is a key to preventing worse regressivity in the property tax structure than already exists. The goal is to ease the property tax burden, not make it more or less burdensome to a particular population in Florida. The Philadelphia Federal Reserve also suggested using modern appraisal methods, such as synthetic assessments tied to transactions, to reduce the property tax liability for lower-income households. According to the authors, the total household wealth of lower-income Florida homeowners could increase by as much as 10% if such reforms were implemented.

Spending Caps Tied to Less Than Population and Inflation

The most effective guardrail is a spending cap that limits any growth of state and local budgets to less than the sum of population growth plus inflation. This formula ensures that the government grows in line with the average taxpayer’s ability to pay for spending, preventing runaway budgets.

- Evidence: Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR) demonstrates the power of such a limit, even though voters have occasionally suspended it. Texas’s recent experience, however, highlights the weakness of partial limits, which are often riddled with loopholes, allowing local spending to surge despite property tax rate compression. Florida can learn from both by adopting a universal, airtight cap.

Constitutional Protections

Any reform must be enshrined in the Florida Constitution to ensure permanence. This should include:

- A ban on reintroducing school property taxes once eliminated.

- Requirements that voters approve any new or increased local tax.

- Prohibitions on local income taxes or resource severance taxes, as they undermine competitiveness and growth.

Use of Surpluses

Guardrails should mandate that most, if not all, revenue collected above the spending cap be used for tax relief, rather than for new spending. This is the principle behind the surplus-driven buydown model in Texas, though Florida can strengthen it by making the requirement automatic and binding.

Bottom line: Safeguards are not side issues—they are the foundation of any serious property tax reform. Without constitutional spending caps, levy limits, and transparency rules, Florida risks repeating the failures seen in other states where short-term relief vanished under the weight of unchecked government growth.

Conclusion

Florida stands at a crossroads. Property taxes—once justified as a simple, reliable source of local revenue—have grown into a heavy burden that undermines homeownership, squeezes renters, penalizes businesses, and threatens the state’s long-term competitiveness. Despite assessment caps like Save Our Homes, local collections have consistently outpaced population growth and inflation, leaving families and businesses paying more each year with slight improvement in services. Governor Ron DeSantis and legislative leaders have elevated this debate to the top of the policy agenda, reflecting the growing frustration of Floridians. Yet the path forward requires more than short-term rebates or piecemeal fixes.

Property tax relief—whether through incremental measures, surplus-driven buydowns, or a broader sales tax swap—will only succeed if paired with strict spending limits tied to any growth less than population and inflation. Without fiscal discipline, any relief will be temporary. Florida does not face this challenge alone. States like Texas are experimenting with surplus-driven rate compression, while Montana and Wyoming are debating consumption-based alternatives. Each approach carries trade-offs, but all recognize the same truth: property taxes are among the most distortionary and regressive ways to fund government.

For Florida, the question is not whether property taxes should be reformed, but how far and how fast. Policymakers have a range of tools—from levy caps and homestead adjustments to sales tax swaps and local compacts. The best strategy may be a hybrid approach: incremental relief today, coupled with a long-term commitment to fiscal restraint and structural reform. Ultimately, this debate is about more than revenue. It is about restoring the principle of true ownership; ensuring that families do not spend their lives renting their homes from the government. A tax system should fund limited government, not perpetuate dependency or penalize wealth creation. Florida has the opportunity to lead the nation in this next era of tax reform. If lawmakers can combine fiscal discipline with bold, transparent solutions, they can ensure that Floridians enjoy not only lower taxes but also lasting economic freedom and prosperity.