In December 2018, Minneapolis became the first city in the United States to eliminate single-family zoning through the Minneapolis 2040 Plan. The move attracted national attention. NBC News reported that “a program in Minnesota might hold one of the keys to fixing the problem [of affordable housing], even though it has faced a fair share of controversy.” Minneapolis had opened:

…the door for developers to build multifamily buildings on lots where a single-family home used to be…the city invited developers to mix up the types of projects across different neighborhoods, including units specifically for affordable housing.

The plan included other reforms, such as the elimination of parking requirements and a priority on designs favoring public transit users, pedestrians and bicyclists.

Has it worked? A new paper titled “Zoning Reforms and Housing Affordability: Evidence from the Minneapolis 2040 Plan” by economists Helena Gu and David Munro “estimates the effect of the Minneapolis 2040 Plan on home values and rental prices.”

They do so using “a synthetic control approach” which essentially means that they construct a “synthetic” version of Minneapolis based on data from similar cities and compare the performance in this “synthetic” city, where the Minneapolis 2040 Plan wasn’t enacted, with the actual city where it was.

Gu and Munro:

…find that the reform lowered housing cost growth in the five years following implementation: home prices were 16% to 34% lower, while rents were 17.5% to 34% lower relative to a counterfactual Minneapolis constructed from similar metro areas.

This seems like a ringing endorsement of the Minneapolis 2040 Plan, but there is a little more to the story.

Gu and Munro look at how enactment of the Minneapolis 2040 Plan led to lower home prices and rents in the city and find that:

…the reform did not trigger a construction boom or an immediate increase in the housing supply. Instead, the observed price reductions appear to stem from a softening of housing demand, likely driven by altered expectations about the housing market.

This demands further explanation. Gu and Munro note that “The pandemic induced large-scale population movements, and cities that experienced significant inflows often saw housing demand – and prices – rise sharply” but that this was not the case for Minneapolis which “experienced relatively modest population growth during this period, with an average annual growth rate of approximately 0.18% between 2020 and 2023.” Was this soft demand for housing in Minneapolis simply a result of fewer people wanting to live here?

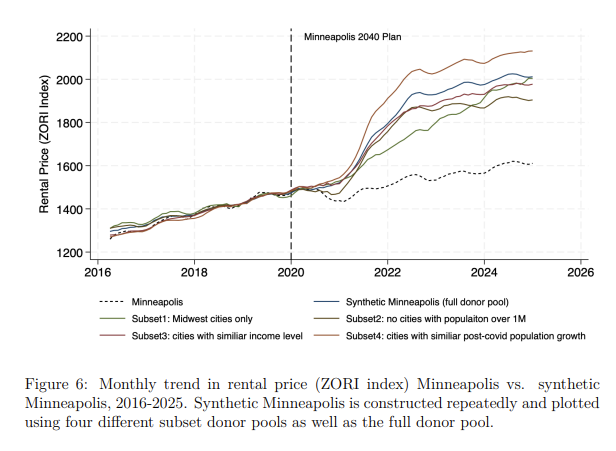

This does not appear to be the case, at least in Gu and Munro’s findings. To test this theory, they “construct a subset donor pool limited to cities with similarly moderate post-COVID population growth, defined as ranging from –0.3% to 0.5%. As shown in Figure 6, the estimated treatment effect in this subset is approximately $100 larger than the baseline estimate by the end of 2024.” In layman’s terms, the difference in rents between actual Minneapolis and “Synthetic Minneapolis” was $100 larger when accounting for population growth. This, the authors argue, indicates “that the main findings are not driven by pandemic-related housing booms in other cities.”

So what are they driven by? “[T]he zoning reform itself may also play a role in moderating demand,” Gu and Munro note:

By signaling a future expansion in housing capacity, the reform likely shifted expectations among home buyers and investors. Anticipating a more elastic housing supply and a less heated housing market, potential buyers may have delayed their purchases or reduced their bidding aggressiveness. These expectation-driven behavioral shifts can suppress price growth even in the absence of immediate construction activity. In this sense, the reform’s impact on market sentiment may have contributed to the observed price declines through a reduction in speculative or urgency-driven demand.

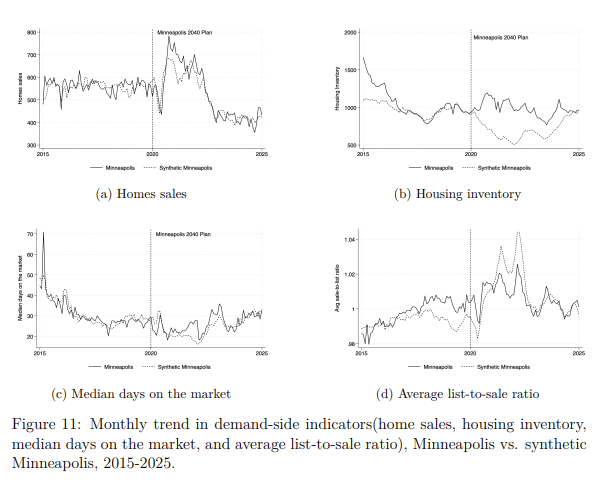

To test this hypothesis, we examine a series of demand-side housing market metrics to examine how the Minneapolis 2040 plan affected the housing demand. Figure 11 reports the monthly change in home sales, housing inventory, average list-to-sale ratio, and median days on the market for Minneapolis and synthetic Minneapolis. Beginning in early 2021, Minneapolis experienced a slight relative increase in median days on the market, a more notable increase in housing inventory, a slight decrease in average sale-to-list ratio, which are generally consistent with softened demand and a less heated housing market.

…

Readers can judge for themselves whether the differences between Minneapolis and “Synthetic Minneapolis” on these metrics post-2020 are all that large, and a comparison with the differences before 2020 is useful here. The largest is clearly for Housing Inventory and for all four the differences seem to have vanished, and for Home Sales, Median days on the market, and Average list-to-sale ratio, that convergence occurred by 2023.

“The most optimistic interpretation of this softening in housing demand is that prospective homebuyers and investors anticipate a long-run expansion in the housing supply,” Gu and Munro argue.

However, an alternative and less favorable interpretation is also plausible. The broad relaxation of density restrictions may have lowered the perceived amenity value of Minneapolis for some buyers. In particular, concerns over increased density, congestion, or neighborhood change may have reduced the city’s attractiveness to marginal buyers, leading to lower demand (Davis et al., 2023). While there is currently little evidence of a large-scale residential flight, such sorting effects often unfold gradually. Future research should further explore whether zoning-induced changes in neighborhood character influence longer-term residential preferences and mobility patterns.

We look forward to reading it.