The Learning Curve Mike Goldstein & Sean Geraghty

[00:00:00] Alisha Searcy: Welcome to the Learning Curve podcast. I’m your co-host, Alisha Thomas Searcy, and joined by our other co-host, Dr. Albert Cheng. Hello, Albert. Hey, Alisha, what’s going on? Thanksgiving was wonderful. The holiday season has officially started and uh, it’s cold outside. Yeah. So things are going well. What a, you know, what a wonderful time of the year, huh?

[00:00:45] It is. Not that I necessarily like the cold, but you know, it’s all a part of the process, a part of the season. So it’s a good time. It is, it is indeed. I hope that your family is well and you had a nice Thanksgiving.

[00:00:57] Albert Cheng: I did. Yeah. My sister’s family visited and so, uh, my kids got some cousin time and it’s all very good.

[00:01:04] Alisha Searcy: That is so important and so special. You know, thinking about growing up, some of my most fond memories were being around cousins and creating those memories. So that’s such a gift. I totally agree. Well, very good. Well, we’ve got a great show today, so I’m looking forward to the conversation that we’re gonna have about ADHD.

[00:01:23] Hmm. So that’s gonna be really good. Looking forward to that. But of course, before we jump into our guests and our topic of the day, it’s time for some articles of the week. Would you like to tell us what you’re reading?

[00:01:34] Albert Cheng: Sure. Yeah. I found a really fascinating one. You know, Alisha, we, we talk a lot about literacy on this show and science of reading.

[00:01:42] So my article’s about reading, but it’s not about the science of reading. It’s, uh, so here’s the headline. I’ll just give it to you why parents aren’t reading to kids and what it means for young students. And so this is a article from the 74. It covers just that topic, including some recent surveys that were done, finding that less than half of children, ages zero to four are read to daily.

[00:02:03] And the article. At least the author interviews some experts on reading and children’s literature and you know, why is this happening and what are the consequences? You know, many of us probably listening on the show have heard about the importance of reading to kids and how that’s important for developing.

[00:02:20] I mean, later literacy, you know, content knowledge, and I won’t. On about the details of the article, just flag it. And I think it raises an important point about reading to our kids. It reminded me of a book that my wife came across called The Enchanted Hour, written by Megan Cox Guden, and essentially this enchanted hour is this hour where parents read to their kids, and I just want to take the time now to.

[00:02:44] Give my wife kudos and my utmost gratefulness for her love of books and her dedication, always reading to our now 3-year-old, but also even to our 1-year-old who might not hold attention to a single page for very long, but he’s always, uh, grabbing for a book and yeah, coming to either me or my wife and babbling to look at it with us.

[00:03:05] So my wife deserves a lot of credit for her investment in that.

[00:03:09] Alisha Searcy: Yes. Agreed. And you know, it’s interesting, that’s such an important article and it’s kind of sad because it’s so important if you, you know, know anything about literacy, you know, you start teaching your kids to read as early as utero. You know, I remember reading to my daughter while I was pregnant with her.

[00:03:29] I’m a little Teapot, I think was her favorite book while I was pregnant. Um, and then I would, you know, often read it to her when she was a newborn. And to your point, part of literacy is them grabbing the book and, you know, touching, feeling, hearing the words. And it’s so important for that early. Process, right?

[00:03:51] Yeah. So for reading, for writing, for comprehension, and we often talk about in K 12 education that kids who. Kind of have a head start and they’ve heard at least 1 million words by the time they reach kindergarten. You know, it’s helping them to be prepared. And part of that million words is having been read to.

[00:04:11] Yeah. So it’s so important. So yes, kudos to your wife and to all of the parents who are reading to their kids at an early age. Yeah, don’t stop. It’s so very important. Even if you think they don’t care, they’re not interested.

[00:04:23] Albert Cheng: It’s all a part of the process and, and yeah, that’s what we found in our experience and this.

[00:04:28] Cultivating a love for books, you know, I mean, look, my one year old’s like understand all this stuff, but he’s grabbing a book. He’s seeing my wife, his older brother, myself, hold a book. And I don’t know, I mean, I don’t know the any, if there’s any research on this, but I gotta think the more kids see adults and other kids holding books rather than say like a device.

[00:04:50] There’s something about the book, right? Yeah. It’s this one. And I don’t know, maybe there’s something about that that cultivates a love of reading, which is important.

[00:04:57] Alisha Searcy: I’m almost positive the research says that you’re, you are exactly right and it’s, you wanna make it a, a norm in your household, in your life, you know, just a part of your daily practice to just read.

[00:05:09] So that was very important when my daughter was growing up, was like, let me, I want her to see me in a book. She sees me on my phone a lot too. Yeah. But she also sees me in the book, so, yeah. And she, she’s hopefully, she’s in college now. I hope she still reads more than just. You know, the class assigned assignments, so we’ll see.

[00:05:26] I’ll have to ask her about that. So, great article. Thank you for that. I have one that’s probably a little bit more serious. Ooh. From Politico, it’s called The Challenge of Moving Special Education out of the Education Department. I raised this article and this issue because I just want our listeners to know and be aware of what’s happening.

[00:05:47] We all care very deeply about education and what’s happening in our country. I mean, we know that there was a promise made during the campaign that the education department would be eliminated, and I’m not exactly sure why. Albert, I don’t, and you may not have the answer to that either, but I’m just thinking of all the federal departments that we have, why education has to be the one to be eliminated.

[00:06:15] So it’s a question that I just keep pondering, you know? Yes, we deal with education every day and so naturally. One would say, and I certainly would say there’s nothing more important than having an education and making sure that we have a strong K 12 system in this country. So I’m very baffled about why there’s a very intentional effort to eliminate the department, and so since it can’t be done.

[00:06:39] Just by executive order because it’s in law and was started by former governor and former President Jimmy Carter. They can’t eliminate it fully. And so they’re instead moving different departments out. And so in this case, and this article talks about removing special education from the Department of Education, which creates a lot of alarms.

[00:07:00] And it’s interesting, uh, you know, later today we’re gonna be talking about. A DH adhd. Uh, and with the permission of my daughter, she has ADHD and has allowed me to be able to talk about this publicly. She also has had an IEP while going through elementary, middle, and high school. And so when I think about the Department of Education, I think about federal laws around IDEA.

[00:07:24] You know, which is the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which it, you know, essentially says here are the laws and the rights that students have. You need a department, a group of experts in this case who know the law. Who want to make sure that the rights are being protected by students. And so arguably, Albert, I think this is a little bit scary for a lot of people to know that special education is moved.

[00:07:49] I think it’s gonna be moved to the Department of Labor. I don’t know exactly where it’s being moved, but it just doesn’t seem to make sense to me. And so one of the things that Secretary McMahon has said is that. She thinks the shutdown, the longest shutdown that we’ve had in history proved that her agency is unnecessary.

[00:08:10] I certainly don’t agree with that. There are also a number of people who were laid off during the shutdown and now it’s been stopped by a court, and so there’s a lot of back and forth, but at the end of the day, again, what I want to raise here is we need to make sure that the rights of students are being protected, especially our very vulnerable students who have very significant challenges, whether it’s physically, cognitively, emotionally, et cetera.

[00:08:37] We have the department, we have. Special education set up so that they will have a right to a public education so that they can be served, have the accommodations that they need. And so if you leave all of this to the states, if you don’t have people within the federal departments who are not experienced in this area, who are left to be the experts, I think it’s problematic.

[00:09:00] And so I hope that something will happen. I think the last time we saw a major move like this, where $7 billion were being withheld. At the Department of Education, there was a bipartisan move from US Senators to stop it. And so I hope that something similar will happen that you know, again, partisanship will be put aside.

[00:09:20] People will focus on what’s best for kids, and this department will be restored fully, the Department of Education as well as special education.

[00:09:29] Albert Cheng: Yeah, I mean, look to the families out there with disabilities. I know that it’s for a lot of ’em, some sense of uncertainty around all the changes that are going on.

[00:09:36] And, you know, we get it here on the show and let’s keep an eye out on, on how things unfold and keep assessing and make sure you know, the needs of all of our students, and particularly in this case, those with special needs are still met. So yeah, definitely important to issue, uh, Alisha, and thanks for sharing your thoughts on that.

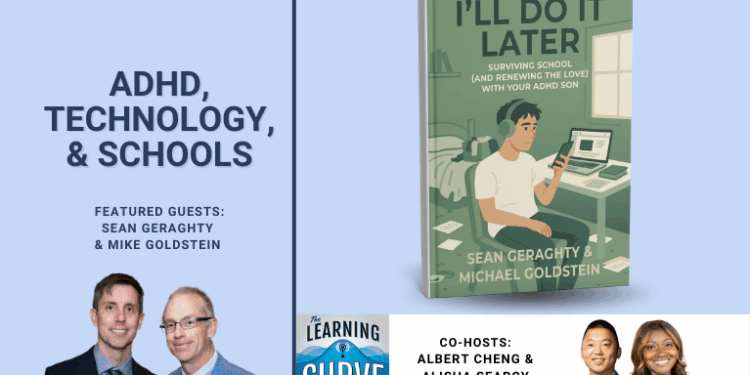

[00:09:52] Alisha Searcy: It is, of course. So on that theme, we have a great show today. We have Sean Garrity and Mike Goldstein, who are co-authors of, I’ll Do It Later, surviving School and renewing the Love with your ADHD son. And so looking forward to that. So make sure you stay tuned.

[00:10:23] Sean Garrity is a co-founder of Reset Team Coaching. He has worked both at small Scale teaching high school Math in Chicago and large Scale as Chief Academic Officer of Bridge International Academies over 2000 schools in Africa and India. Sean has a master’s degree in education from Harvard. Mike Goldstein is the co-founder of the Center for Teen Flourishing.

[00:10:46] He’s worked with Sean for 13 years and before that founded Match Charter School in Boston. He received a Master’s degree in Public Policy from Harvard University and a BA from Duke University. Welcome to the show, guys.

[00:10:59] Mike Goldstein: It’s great to be here. Thank you for having us.

[00:11:02] Alisha Searcy: So let’s jump in. You have co-authored the new book.

[00:11:06] I’ll Do it later, surviving School and Renewing the Love with your ADHD son. Would you talk to our listeners about the background of how you decided to research and write this as well as a few of its overarching themes that relate to K 12 education, policy, and parenting? Help us.

[00:11:24] Mike Goldstein: Alright, Alisha, it’s great to talk to you and Albert, I’ll start.

[00:11:27] This is Mike from Boston and Pete Peters, one of the big things he accomplished in founding Pioneer Institute was charter schools in Massachusetts and I was one of the early founders of a charter called Match and it started as a high school and we preached a lot of things like grit and responsibility and perseverance and things like that.

[00:11:52] And we had a fair amount of success. But one thing we noticed over the years, and this was true as you know, with charters nationwide, is we would lose a lot of high school students that would transfer back to district schools. And then we often had some of our kids who would be the first in their families to go to college, would not succeed in college.

[00:12:15] And I worked in charters for 15 years. I got interested in the puzzle of why do some kids, even when they kind of connect well with their teachers and try in good faith to kind of pay attention during the school day and get their homework done at night really struggle and ultimately find themselves unable to do that.

[00:12:37] And so that’s been a now a professional life quest for me for a long time. Alisha, that’s how I got started in this.

[00:12:45] Alisha Searcy: That’s really interesting and super helpful. So quote, I’ll do it later. Every parent of an ADHD team knows this phrase.

[00:12:53] Mike Goldstein: Yes, we do. Um, do you have one, Alisha?

[00:12:57] Alisha Searcy: I do. I have a daughter who’s now in college.

[00:12:59] Um, nice. ADHD. And so we know this as it says, it’s not defiant. Exactly. It’s not a lie. Exactly. Your son probably means it when he says it later. It just never quite becomes now, end quote, and this is what you write and I’ll do it later. And so can you talk about the diagnosis of ADHD among young people in America and across the globe?

[00:13:22] Mike Goldstein: Yes, Sean, you should speak to that. But Alisha, I bet the listeners would love to hear another couple lines about what was your experience as the mom of a teen with ADHD? Like, did that cause any type of clash with you? Were you kind of always, did you feel like you were nudging her to get stuff done, or how did that play out?

[00:13:43] Alisha Searcy: All the time until I realized what it meant. So at first, you know, I’m a type A personality, very organized, structured. I want things done quickly, and I would ask her to do things and it didn’t quite work. As well, or like I would want things done. And then when I realized it’s really not her, you know, wanting to be disobedient or you know, just be disrespectful, it really is the way her brain works.

[00:14:11] And so I had to adjust to how to ask things. You know, maybe she needs a few more reminders. Maybe I’ve gotta help with the executive functioning skills. And so, yes, it can be very, very frustrating if you don’t understand it and you don’t have the patience to figure out how to support them.

[00:14:29] Sean Geraghty: We think. Yeah.

[00:14:29] So that, I’m sure there’s lots of smiles and nods and recognition among your listenership. We see the same kind of thing. We, we understand the condition as I think it’s been helpfully reframed less as a deficit of attention and more as that variance of attention. Mm-hmm. So lots of teenagers that we work with struggle perhaps more profoundly with things that they don’t find stimulating or engaging or motivating.

[00:14:51] But conversely, maybe can fall into these states of intense focus, sometimes called hyper-focused on things that they are interested in or that are stimulating or that are engaging. Sometimes those things aren’t the most productive phones make this very challenging, but that’s the big picture of how we understand it and we, we have noticed.

[00:15:09] Followed with great interest like the RIDE and ADHD diagnoses, what precisely to attribute that to, especially given that it tends to flare up in some environments as opposed to others. We’re not exactly sure, but we followed that with great interest.

[00:15:22] Alisha Searcy: Very interesting. Stanford’s Dr. Anna Lemkbe, who we’ve also had on

[00:15:28] Mike Goldstein: Nation.

[00:15:28] Yeah, we heard that Todd. Nice.

[00:15:31] Alisha Searcy: She’s the author of the recent New York Times bestseller Dopamine Nation, and we learned a lot hearing from her. She wrote that the smartphone, to your point, Sean, is the modern day hypodermic needle. Delivering digital dopamine 24 7 to a wired generation quote. So can you talk about the growth of the internet, smartphones, and social media, and how technology is impacting students’, technology, addictions, anxiety, ADHD, and just overall mental health.

[00:16:01] Mike Goldstein: Yeah, I would love to jump in here with a perspective that, look, ADHD kids have obviously been around for a long time, so let’s say 15 years ago before smartphones were introduced. We still had a lot of kids who fit your daughter’s description, and I thought you said something really important that I just wanna circle back to from the point of view of a school leader or a teacher, a lot of times they need the epiphany that you had, which is they’re starting from this point of view of like, Hey, I’m kind of type A, I get my stuff done, and I working hard to build a relationship with you.

[00:16:40] And if you’re not getting your stuff done, I see it as almost like, you’re rejecting me. You’re, you know, and then at some point you realize, oh, that may be true, maybe that the relationship isn’t enough to motivate them. But a lot of times it’s like, no, you did reach me. I just still find myself floundering to get stuff done.

[00:17:01] That’s long been true. That’s always been true. That’s been an issue for schools like KIPP and so forth, networks of charters that said. Wait a minute, we’re not gonna be like your former traditional public school where you’re just allowed to kind of goof off. We’re like gonna put all this extra adult energy into you and we’re gonna believe in you.

[00:17:18] And we’ve got these other kids that you know in your class that are now doing well, but you are not. What’s the issue? I ran a school like that and what I would say is. Smartphones now have made that, let’s say 50% harder. Mm-hmm. Like the kid who struggled at 7:00 PM to get her stuff done or his stuff done.

[00:17:39] Well now it’s like even if you try to put your stuff away, it’s always kind of around nearby and the moment your dopamine to use Annas phrase becomes unregulated, you find yourself involuntarily grabbing for, you know, the screens that will kind of readjust your dopamine and de Sean’s point, get you sort of back to stuff you find interesting.

[00:18:04] So it’s made it a lot worse. I do think there are some things that school and policy people can do about this that are separate from what parents, we usually work with parents with our reset team coaching, but we feel like there’s some things that school leaders and policy makers could do to kind of adjust to this stuff.

[00:18:25] Alisha Searcy: Absolutely. It’s so necessary. One of the things I’d love for one of you to talk about, or both are the case studies of your book, you have quote, part of the work of this book is figuring out how to support guys like that. Guys like us. Now let’s turn from these personal stories to the four composite case studies that form the heart of this book.

[00:18:47] These are different teenagers drawn from our work with many families, each showing a distinct pattern of ADHD you may recognize at home end quote. So this is what you write in your book. So would you quickly sketch for us these four composite case studies that you draw lessons from?

[00:19:05] Sean Geraghty: Sure. Yeah. So we wanted to do something different with the book just in the big picture, which is lots of parents find themselves when looking for help on how to manage ADHD, their own or or their child’s.

[00:19:17] See lots of books, lots of subreddits, lots of YouTube videos, lots of podcasts. And throughout we would say the dominant technique there is to just present a lot of strategies. Here are 25 strategies you could try, and our experience with practitioners was always. Yes, it’s good to have a bank of strategies, but lots of times these things may or may not work depending upon lots of different factors.

[00:19:39] So we thought that parents might find it more useful to, again, perhaps smile and recognition, or even not in recognition at actual case studies, actual trial and error. One of the things we try to do through the book with the case studies is say, Hey, this thing that we tried with Alan, for example, do you think it works?

[00:19:55] Do you think it didn’t work? And it’s not gotcha as much as it’s us just trying to say. This is a process of trial and error that you can’t easily predict in advance. And so as a parent, it’s all good. Feel good for every five things that you try. Maybe one or two things might work, and even then, only for a month or two.

[00:20:12] So begin again and get going. With the four case studies, we tried to tell different stories with each. There’s Alan, he was more of an academic. Struggler, had a couple D’s than an F, but felt like he could. Just by his own natural verb and charm and sort of ability to get things done at the last minute, kind of elevate.

[00:20:29] Of course that drove his family a little bit crazy, to be honest. That’s one. Manan was a guy who initially was doing really well in school, had as through eighth grade, and then as like the rigor of his very challenging high school piled up. He found himself struggling. His mom late in life, ADHD diagnoses herself, saw a lot of herself in him and tried to help.

[00:20:52] Terry is a guy who was thriving socially and then just sort of got captured by the phone in large part. And then Silas was a college freshman who I think also struggled with, at least I’m, I’m curious about your own daughter’s experience. College can be both freeing for the d ADHD mind, but also quite challenging given how structureless it is relative to high school.

[00:21:09] So those are our case studies and that’s our big picture.

[00:21:12] Albert Cheng: Well, Sean and Mike, I mean, thanks so much for joining us and, and I’ve been fascinated listening to all your insight into this. We often talk about NAP scores and math and reading achievement. I mean, it’s an education podcast, but I’m wondering, you know, what does your book have to say to readers parents, ADHD students alike who are struggling to, uh, keep on track with academic achievement?

[00:21:33] Mike Goldstein: Yeah, Albert, I agree with, you know, people like Marty West at Harvard who sort of draws the line between declining NAP scores and some of the Jonathan Het anxious generation smartphone screen time stuff. I think Sean and I see that as causing some of the achievement loss, but it’s not obvious. How do you get it back?

[00:21:56] And I think one thing we would say to parents that. When you’re a parent, I mean I, I’ve got two teens myself, Sean has three kids. You wonder sometimes what are the things where you try to get help from an outsider and what are the things where you kind of do it yourself? So if you have a medical issue, you’re clearly not gonna try to do it yourself.

[00:22:19] You go to the pediatrician legal issue, you go to a lawyer. But there’s other stuff that you kind of figure, oh, I’m a parent. Like I can sort of teach them. Obviously like we’re gonna teach them how to ride a bike. We’re gonna teach them, you know, how to share with other people ADHD and its impact on achievement falls in this middle zone.

[00:22:39] Because what happens is usually this stuff is hitting at the exact moment when the kid as an adolescent is pushing away from their parents. So Sean described the case study of Manan. This is a pretty common story with ADHD kids. ’cause in the US a lot of homework doesn’t really kick in until high school, and that’s when a lot of the learning is supposed to happen by homework.

[00:23:04] Homework is kind of like the death nail of a lot of ADHD kids, right? I go upstairs after dinner, I mean to do it. I never get it done. Next thing you know, it’s one in the morning and nothing’s done. Now what happens? And I think that the parent who thinks I’m gonna personally be the kid’s homework coach runs into real life, which is the kid’s kind of biologically wired to start pushing away from the parent.

[00:23:30] And so that’s a very common story that we hear, and the idea of like getting help from other people is probably going to be an important part of how you would help. Kids that are struggling to achieve at the high school level, get back on track. Often this is not a parent delivered solution, but the kid does need someone who’s gonna rewire what their, you know, let’s say 6:00 PM to midnight time is like, without that, you’re not gonna see their achievement.

[00:24:01] How to get back to where it should be.

[00:24:03] Albert Cheng: Well, let’s keep hammering on this topic of just addressing these special needs. States across the US are trying different policies, and one of the ones that we talk about quite a bit on the show is policies around literacy instruction and science of reading. Do you see that playing a role in addressing the special needs of ADHD students?

[00:24:23] Mike Goldstein: I think that solves a different issue. An important issue, right? Albert, which is states system strayed from pretty common sense, phonics instruction and other things that we knew worked for kids and they just sort of didn’t fit the vibes of teachers for a while and boom, it kind of went away. Now states like Mississippi have kind of brought it back.

[00:24:45] I think that’s good. And so we see in some of these states, fourth grade achievement. Coming way up in some of those places. However, interestingly at Mississippi, like eighth grade scores, 10th grade scores on a, we still see in the states that are doing science of reading, we don’t really see a recovery. I think that one seems to be a different problem.

[00:25:05] The high school age seems to be a different empirical problem from the younger kids. The science of reading stuff, and I think some of it again, is if you just follow the Dopamine Nation Trail. You say, Hey, let’s invent a system that is most likely to trip up high schoolers. It would probably be a lot of the important practice in math and English that you’re supposed to do.

[00:25:35] It’s supposed to happen in the hours where you’re least monitor. Where your screens are most present and there’s the least human support to you. Mm. That that would be like, and that’s what we’ve built. So I think that’s sort of the puzzle that we need to kind of unwind.

[00:25:53] Albert Cheng: Let me, uh, raise a slightly different topic.

[00:25:55] I mean, you might know, be familiar with UCLA professor Maryanne Wolf. She’s the author of Reader Come Home, the Reading Brain in a Digital World. And the other book covers quite a bit about brain science and the insight that that’s telling us about acquiring knowledge through printed or written word and, you know, digital media.

[00:26:16] So how should educators and parents be thinking about technology use in school at home? I mean, you’ve alluded to some of these points, but yeah, I’d like to just hear more about, you know, what you have to say regarding technology use and kids with ADHD.

[00:26:31] Sean Geraghty: I think Maryanne calls out a number of like important questions in her book.

[00:26:34] I think very consistent with what we’ve observed in our practice. Albert, I would say this idea that, and maybe there’s the think piece every month, the Atlantic, the New York Times, new Yorker, writing about the decline, let’s say in attention spans. Leading to the consequence of kids not being able to engage with Pride and prejudice, for example.

[00:26:51] So we, we have a little bit of a detour in our book that sort of addresses that question around what’s sort of happening here. Our experience as practitioners has been, again, consistent with what Mike was saying. Very much in tune with that, which is, it’s hard to do things that are unpleasant, that require sustained engagement.

[00:27:08] It’s perhaps harder because the opportunity costs are so high. Your phone is right there. That’s what with some of our guys, we say the phone’s gotta be at least four rooms away. Like, you know what I’m saying? Like you gotta almost symbolically lock it up or literally lock it up or give it to someone who you know won’t give it back to you.

[00:27:22] And so yeah, we see that. One of the things I like about her book is that. She too is describing her own battle. Similar to Dr. Lemkbe, they’re describing their own battles with these things. It’s not just with teenagers. We’re seeing this with adults as well, and so how do we. Draw on the neuroscience, draw on the literature, et cetera, to make for a better experience in our work.

[00:27:40] That’s really like rule number one is try to control the environment as much as possible. Mm-hmm. Mike and I always joke like, get out of the room. If you can get outta your bedroom, if you can be at the kitchen table doing your work, or at a library, or even at Starbucks, someplace where there’s a little bit more built in accountability, we think that tends to help.

[00:27:57] But as for the sustained silent, quiet reading. The pleasures of, for example, great expectations or Shakespeare. We’re not exactly sure what happens next there, uh, but we’re counting on a dozens more think pieces to help us sort it out. Yeah.

[00:28:12] Albert Cheng: Let me ask one last question just to give you both a shot, to leave us with your best recommendations and, and actually, so I mean, your book.

[00:28:20] You conclude by saying quote, this gets easier, not harder. As kids hit age 22 and beyond, the teenage years are actually the worst time for ADHD kids. In many ways. They have adult sized responsibilities, but child sized executive function skills in environments that offer less structure than elementary school, but more pressure than they’ll face in most adult jobs, end quote.

[00:28:44] So it’s a big problem. Offer us some takeaway recommendations from the book and any wisdom you have about how ADHD may become easier as teens, brains fully develop in college or as they age into their twenties.

[00:28:58] Mike Goldstein: Yeah. Albert, I’ll take a shot to start. One is, I think screens overall, the degree to which these are embedded in every part of the school day, math, english, science, history, the portals that are supposed to track the assignments.

[00:29:12] All this stuff makes things worse for ADHD kids. ’cause it’s sort of like it used to be back, Albert, I’ll put us, you and me together. Like in our day, right. You could sort of say, alright, I’m gonna go to the kitchen table, I’m gonna take out my copy of, you know, great expectations. I’m gonna grind my way through chapter 23.

[00:29:34] And now it’s like almost all the assignments are literally on a laptop or phone.

[00:29:40] Albert Cheng: Yeah. Yeah.

[00:29:40] Mike Goldstein: So. That’s bad. I don’t think schools will easily be able to do this. I think school choice will help here. ’cause I do think you will see some schools start to emerge that sort of put this problem front and center, but that’s kind of a long road, not a short road.

[00:29:56] Second thing is having myself done a podcast for Pioneer Institute about homeschoolers. I love the idea of school choice education savings account. These are important policies, but for your listeners who advocate for those policies, they often make things worse For ADHD kids, think about an ADHD, 15-year-old who was in school at least.

[00:30:19] Sometimes the teachers were kind of like, Hey, young Albert, like, kind of get your but in gear. Let’s get going here. Now they’re kind of sometimes lost in their bedrooms and you see. Homeschool threads often filled up with moms who are very concerned about their kids because they notice this behavior and they’re not sure what to do about it.

[00:30:40] So I think like there’s some, you know, intersection here of ADHD and school choice, that school choice advocates would be wise to get on top. And I think the final thing would be if I, you know, rewound my life 30 years and restarting match charter school. I would create some type of option where for maybe a few nights a week, the kid could stay at school, like have dinner, be there longer.

[00:31:09] Maybe it’ll 8:00 PM but. All of the homework would be with a support team. You know, like that kind of structured steady team where the wifi would be turned off, everything would be back to pencil and paper. You would be on an opt-in basis only, but a deal you would essentially offer to the ADHD team is.

[00:31:30] If you’re willing to put in a few like extra chunks, maybe Sunday afternoon, Monday night, Tuesday night, we’ll engineer your school day. So you literally don’t have homework that you’re supposed to do every night after dinner, and we can kind of meet you where you are. So you’re giving something, we’re staffing it, we’re taking away the tech-based thing, and we’re just gonna make it more possible for you to do in good face.

[00:31:54] You’re almost like rewinding the era. Some version of 2005.

[00:32:00] Albert Cheng: Yeah. Sean, any last words of wisdom or recommendations you’d leave us with?

[00:32:04] Sean Geraghty: I think that’s right. I think like this idea of, given that it flares up and Alisha, it was so again, nice to hear about your daughter earlier. Given that this is so much a function of the environment, we find that high school and college it for different ways are ill suited to the condition for a lot of the reasons that Mike is describing.

[00:32:21] One maybe has too much structure, one has too little. But when you’re able to enter into the professional world, when you have more control over your own time, at least nominally with what profession you choose, we find that the symptoms naturally tend to decrease. Right. Paul Tough just wrote like a giant piece in the New York Times about this.

[00:32:37] That makes one of, among other points, makes that central point, which we found to be true. So we often use the metaphor of Waystation. You’re just trying to get through this stuff. You’re building a support team. We do think it’s a chronic condition. You’re gonna need different supports in high school. In college, but once you get to your professional life, you’re still gonna need supports.

[00:32:54] Mike and I write about that even for ourselves, but the nature of them might change so long as you’re replacing the hours of the day that feel like a one or two out of 10 with more that feel like a six or a seven or an eight. All of us here know that it’s not always gonna be 10, but it doesn’t have to be so much.

[00:33:10] Ones and twos like high school can be for a lot of our guys.

[00:33:14] Albert Cheng: Thanks so much for joining us and talking about your book and your insight into this.

[00:33:18] Alisha Searcy: For sure, and I’ll just say that Layla, my daughter, is doing very well in school. She’s still struggling in math. That’s another challenge. But in terms of her executive functioning and time management, it’s been quite fascinating to watch her adapt and kind of figure it out.

[00:33:38] In fact, just a quick store, we’ve got like one more minute. She drove home for Thanksgiving break and it’s a three hour drive. And she left at like six o’clock in the morning. I didn’t even know she was gone yet. So just to see the level of time management, planning, all of those things, no procrastination.

[00:33:57] It’s amazing to watch. And so I think some of it is, yes, we had, you know, some good supports around her, but also like she’s figuring it out and she’s learning what works for her. And so I think for parents. Who have kids who, who have ADHD. There’s hope for us that they learn, they develop, they grow from this.

[00:34:16] And, you know, there’ll still be challenges, but I’m super excited and proud of her. So, and, and very excited to have you guys. So thanks for joining us.

[00:34:25] Mike Goldstein: Love that story. What a great Thanksgiving that must have made. Good start to the holiday. And thank you both Alisha and Albert, for having Shawn and me on your show.

[00:34:46] Alisha Searcy: Albert, that was great. It was all that I hoped it would be. I learned so much. Again, having a kid with ADHD, there’s so much to learn and so much to understand about their habits, behaviors, and I think as parents, those of us who have kids with ADHD, like you just, you never stop learning. So what a great interview.

[00:35:05] Albert Cheng: Yeah. Yeah. And then look, I think that’s the power of books and conversation to better understand the lives of others that you know, that we otherwise wouldn’t have come across. So really appreciate the interview.

[00:35:15] Alisha Searcy: For sure and they’re doing great work. Well, it is time for us to head out, but before we do that, it’s time for our tweet of the week This week it comes from Education Week, and it’s a new analysis shows that some districts are being hit much harder than others when it comes to student enrollment.

[00:35:34] So what an important conversation to talk about in this article that’s about where school enrollment is declining and what the new research is showing. So make sure you check out that article. Albert, as always, great to co-host with you. I love it when we’re back together again.

[00:35:50] Albert Cheng: Oh yeah. Yep. The feeling’s mutual.

[00:35:52] Alisha, always glad to be back and running the show

[00:35:55] Alisha Searcy: with you. That’s right. Now. Be sure to join us next week. We’ll have Erica Donald. She is America’s First Policy Institute’s Chair of Education Opportunity and chair of the A FPI Florida State Chapter. So we’ll see you next week. Take care. See you later.

[00:36:13] Hey, this is Alisha. Thank you for listening to the Learning Curve. If you’d like to support the podcast further, we invite you to donate@pioneerinstitute.org slash donations.