Connecticut towns are meant to be governed by neighbors, taxpayers, and parents accountable to the communities they serve. They are not meant to function as extensions of any single interest group. Yet that distinction is increasingly blurred, as the Connecticut Education Association (CEA) now openly celebrates a coordinated effort to place its members inside the very local offices that oversee school budgets, contracts, and spending.

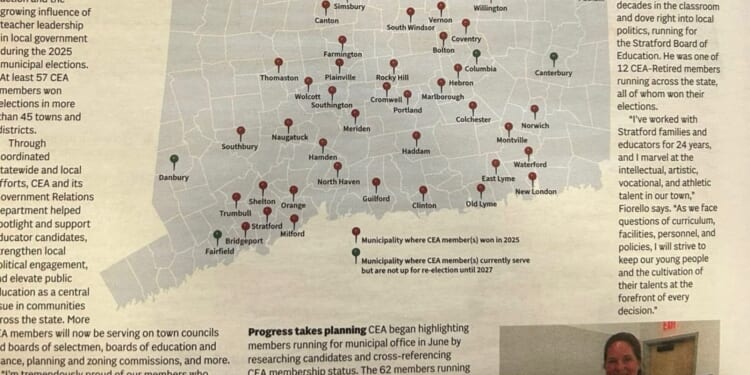

In its latest Advisor newsletter, the CEA announces a “record number of Connecticut educators elected to serve their communities,” complete with a statewide map dotted in red pins marking each victory. Active and retired teachers, the union reports, now sit on boards of education, finance boards, selectmen’s offices, and town councils across Connecticut.

This is presented not as a coincidence, but as a strategic success.

This isn’t some small, organic trend either. According to the union, 57 of its members won elections in more than 45 towns and districts, out of 62 candidates who ran — a 250 percent increase from 2023. The article makes clear this was no spontaneous wave of civic participation. Candidates were guided through a union-run pipeline, including a formal questionnaire process and participation in the National Education Association’s “See Educators Run” program, a national initiative designed to prepare educators for elected officials.

At the same time, the CEA’s Government Relations team worked with local affiliates to conduct coordinated turnout efforts: emails, texts, mailers, phone banks, and door-to-door canvassing that generated nearly 19,000 direct voter contacts. That is not informal volunteering. It is an organized political operation.

If a private-sector union announced that its members had systematically moved into management roles at the companies they negotiate against, it would raise immediate red flags. If a regulated industry celebrated placing its executives on oversight boards, then conflict would be obvious. Yet when a teachers’ union highlights its success in placing members inside the government bodies that set education policy and approve labor contracts, the development is framed as “community service.”

That framing deserves closer scrunity.

Teachers, like all citizens, have the right to run for office. That is not the issue. The concern arises when a labor organization actively recruits, trains, supports, and elects candidates into positions that directly influence negotiations, budgets, and policies affecting that same organization. At that point, the traditional separation between labor and management begins to erode.

Consider the practical implications. A school board member who belongs to the union contracts that benefit colleagues, friends, and potentially themselves. A finance board member who came through a union-supported campaign approves budgets that fund those contracts. A selectman helps set tax and spending priorities that determine whether those obligations can be met. When the same institutional network influences all of these decisions, the checks and balances designed to restrain cost growth weaken.

This matters in a state already grappling with rising education expenditures, high property taxes, and persistent pressure on municipal budgets. School spending is often the single largest line item in local government. If those responsible for overseeing it are drawn disproportionately from the same organization that benefits from higher spending, fiscal discipline becomes harder to maintain.

What is most striking about the CEA’s own messaging is its candor. The union is not downplaying its role or presenting these outcomes as incidental. The map, the language, the celebratory tone reflects a deliberate strategy to expand influence at the local level. This is not power reluctantly accepted. It is power actively sought and openly claimed.

Supporters will argue, correctly, that teachers bring valuable experience to public service. The issue is not individual educators choosing to serve. It is a labor organization publicly describing its success in embedding members across governing institutions that negotiate with, fund, and regulate that organization.

That distinction matters for public trust.

As towns across Connecticut head into future contract negotiations and budget cycles, residents should ask a straightforward question: when decisions about school spending and labor agreements are made, who is sitting on each side of the table—and whose interests are they ultimately accountable to?