Last week, I wrote about the U.S. Department of Education’s newest student protection initiative — a low earnings indicator that alerts prospective students when a school chosen on their FAFSA form has average graduate earnings lower than average high school graduate earnings. In Minnesota, nine out of thirteen institutions flagged for poor student outcomes are beauty or cosmetology schools.

As it turns out, a significant portion of schools across the nation flagged for poor student outcomes are cosmetology schools. The federal government isn’t targeting these schools — the released data simply highlights an unfortunate truth about the cosmetology industry. More than 40 percent of the schools under watch by the federal government for failing gainful employment metrics are cosmetology schools, and 20 percent of the schools currently under increased oversight for potential mismanagement (or heightened cash monitoring) are cosmetology schools.

So, why are so many cosmetology schools considered “low earnings”? Why are many beauticians making less money than if they had only graduated from high school?

High cost schools, an oversaturated market, and low pay

When students choose to become cosmetologists, many choose accredited programs that last a year or more. Students work towards state license requirements, but schools often require additional trainings that exceed state licensure requirements. The national program length average for cosmetology schools is 1,500 hours.

For many, that can get pricey. Cosmetology program tuition at beauty schools participating in federal financial aid programs averages about $15,000. Those schools gain access to Pell Grant funds (which do not have to be paid back) and federal student loan funds. For the cosmetology students who borrow federal student loans, the median debt is $10,000 to $14,000.

A recent New America report suggested that many of these schools aren’t serving potential cosmetologists well. Stories abound of little to no business training, lack of education on common beauty services like braiding or extensions, and a subpar pedagogical experience. Yet these institutions often receive high amounts of federal funding, with their students taking out loan amounts incommensurate with their future earnings.

The federal government has been worried about the industry for decades. A 1993 Education Department Office of Inspector General, or OIG, report found an alarming level of waste within the industry, as many students struggled to graduate and many graduates struggled to find gainful employment. The report suggested that the supply of cosmetologists leaving the for-profit schools routinely exceeded demand. For example:

In 1990, for example, 96,000 cosmetologists were trained nationwide, adding to a labor market already supplied with 1.8 million licensed cosmetologists. Of the approximately 1.9 million cosmetologists in the labor market at that time including recent graduates, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that only 597,000 were employed as cosmetologists because the market was completely oversaturated. Yet the OIG estimated the federal government continued to spend $725 million in federal financial aid funds annually to cosmetology students at for-profit schools.

The New America report notes that lobbyists for cosmetology schools successfully argued that the schools themselves were not responsible for the high student loan default rates coming from their graduates. One AACS (American Association of Cosmetology Schools) representative testified at a 1997 House of Representatives subcommittee hearing that “the sad part is that everyone who takes the time to fully understand the issues involved realizes that the primary factor in determining a student’s predisposition to default are the demographics of the students when they enroll in the school, not the educational quality of the school itself.”

In recent years, cosmetology schools have successfully dodged requirements by the Obama administration and the Biden administration, that attempted, respectively, to use gainful employment regulations to limit or cease federal funds to schools that did not produce salaries higher than high school graduates and to require schools not to exceed state licensure hour requirements in their training programs.

Cosmetology schools often have high-ranking representatives sit on state cosmetology boards, and advocate for expansive licensure requirements. For many, the requirements are more stringent than other industries. In Iowa, for example, emergency technicians, dental assistants, pharmacy technicians, school bus drivers, pesticide applicators, unarmed security guards, and most types of building contractors need less training than barbers and cosmetologists. A 2016 Institute For Justice report found that hair braiding licensure requirements — an industry that does not involve any harsh chemicals, heating, or coloring — stretched as high as 2,100 training hours. Attempts to lower licensure requirements have proven unsuccessful in many states.

One common argument offered by cosmetology schools is that the reports of low graduate earnings are a trick of the data. Since many cosmetologists are self-employed or tipped in cash, vast amounts of real cosmetologist earnings are unreported. (I, myself, repeated this argument in one of my previous pieces.) However, that argument may not actually be true. From the New America report:

[T]he Education Department, under the Trump administration, wrote in a court brief that the cosmetology association provided “no evidence of unreported income being an actual—much less widespread—practice among cosmetology program graduates.” Research led by the economist Stephanie Cellini confirms that tax evasion in the cosmetology sector due to unreported tips is minimal, accounting for only about 8 percent more in earnings, and is insufficient to explain the poor performance of many cosmetology programs in comparison to high school. Even a cosmetology industry-funded survey found that nearly 90 percent of salons report tips on W-2 forms, ensuring they would appear in federal tax data.

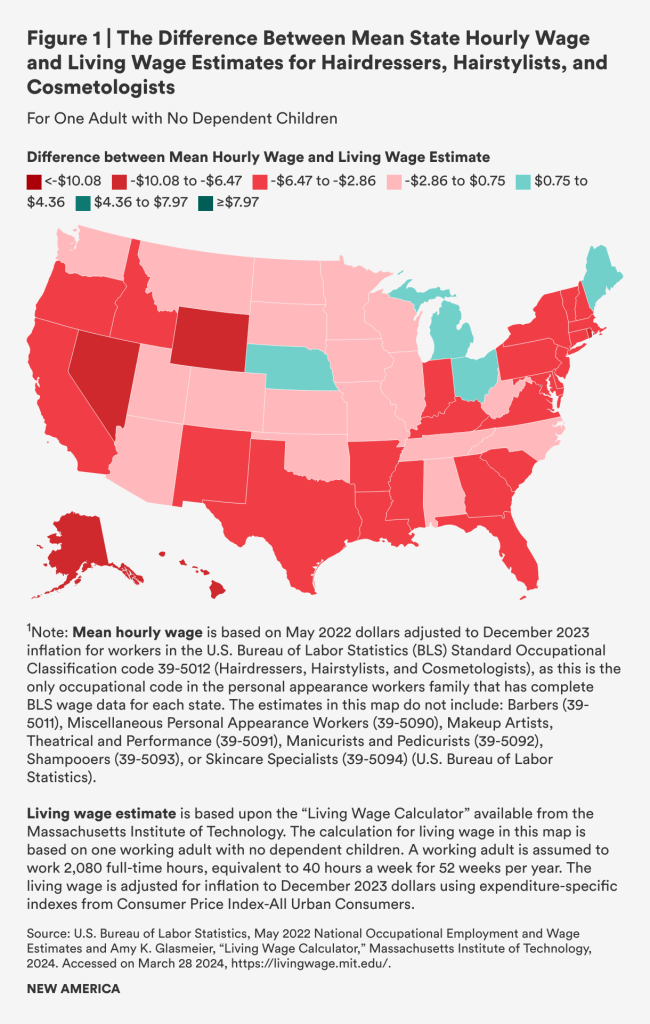

Assuming that we can trust the numbers reported for typical cosmetologist earnings, the prognostication looks dismal. An incredible 80 percent of cosmetology school graduates earn less than they would have with only a high school degree, and earn less than their state’s living wage estimate, with an average five figures’ worth of debt.

Cosmetologists can often struggle after graduation. A cosmetology graduate making the median salary who enrolled in a program that accepts federal aid only makes around $20,000 four years after completing a credential. In Minnesota, the median cosmetologist salary four years after graduation is over $5,000 lower than a high school graduate — and the median student debt is $8,599. Many of these cosmetologists will default on their student loans.

The low outcomes hurt individual cosmetologists, but also hurt the federal government’s fiscal health. Legally, the U.S. Department of Education must cut off institutions’ access to federal aid should large portions of their students default and go at least 360 days without paying down their loans. That aid can be pulled when 30% or more of a college’s graduates have defaulted for at least three years, or 40% or more in a single year. According to 2025 Department of Education data, two out of every five schools currently headed towards collective defaults are cosmetology schools.

Cosmetology schools delenda est?

Cosmetologists do important work, and their skills are always in demand. But prospective students shouldn’t be sold a bill of goods by cosmetology schools who will take their money (and federal money) only to give subpar career results and high loan balances in return.

Policymakers should consider lowering cosmetology licensure requirements, increasing program oversight, and enacting more stringent program requirements. (For example, Minnesota’s licensure requirement that cosmetology schools teach skills for both straight and textured hair is an unfortunate rarity among states.) The federal Department of Education’s recent publication of student graduate outcomes on the FAFSA is a step in the right direction towards outcome transparency. Protecting students who want to make a good living should be a top priority for policymakers.

Sunlight, after all, is the best disinfectant.