We should take the Founders at their word.

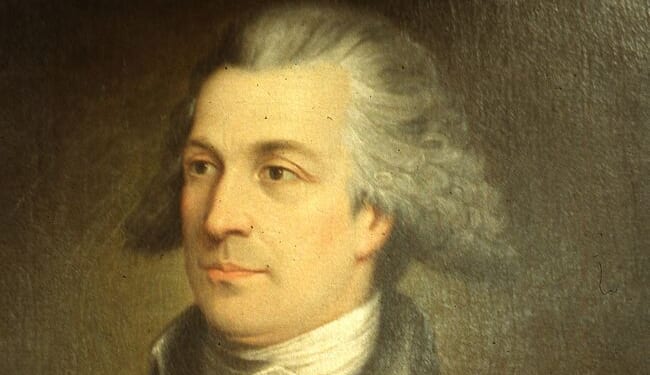

Above: Tench Coxe, whose widely-read articles emphasized the limits on the federal government and the reserved powers of states.

A version of this essay was first published at Civitas Outlook (University of Texas) on January 14, 2026.

“The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the federal government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State governments are numerous and indefinite.”

James Madison

Federalist No. 45

Current controversy over the power of President Trump to send the National Guard into American cities reminds us of perennial questions about the extent of federal jurisdiction: In a system of divided sovereignty, where does central power end and exclusive state authority begin?

Writers on this subject, when they are not merely expressing their political preferences, often focus on the Founding-era meanings of constitutional words such as “commerce.” Few have addressed how the Constitution’s sponsors represented the prospective scope of federal powers to the ratifying public.

For example, the Supreme Court case that construed the Constitution’s Taxation Clause to permit unlimited spending relied on a single claim by only one of the document’s sponsors, Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton’s claim had been hotly-disputed by other Founders and advanced only after the document had been ratified. Moreover, in the first of the two cases principally responsible for widening the Commerce Clause into a power to regulate the entire economy, the court cited none of the Constitution’s sponsors. The second case cited only a statement by John Marshall (who had been a Virginia ratifier) issued long after the ratification, and the court depicted even that statement inaccurately.

The Importance of Sponsors’ Representations

Failure to consider the sponsors’ representations of the Constitution’s meaning seriously impairs the quality of interpretation. The Supreme Court has recognized that, when construing a legal text, pre-enactment comments from the sponsors about the text’s purpose or effect are entitled to “substantial weight.” This is so because voters presumably relied on the sponsors’ representations. By contrast, statements made by non-sponsors are entitled to little weight and those made by opponents are entitled to even less.

Founding-era lawyers understood the value of sponsors’ representations, although they stated it in Latin. Nemo contra factum suum venire potest (“No one may benefit [literally, “come”] in violation of his own deed”) and similar maxims implied that sponsors would not be heard to deny their own pre-enactment representations.

Availability

The historical record is rich with representations from advocates of the Constitution—directed specifically at the ratifying public—on the prospective limits of federal power. The Constitution’s promoters issued these representations before the Constitution was ratified to reassure the public that opponents’ histrionic warnings of central tyranny were baseless.

Some of these representations, such as those in The Federalist, were published in newspapers. Others were presented in speeches delivered in public or at state ratifying conventions. One pronouncement appeared in a private letter.

They took the form of enumerations of activities the Constitution would leave to exclusive state jurisdiction, so long as those activities occurred within state boundaries rather than within federal territories or enclaves.

The Enumerators

A few published enumerations remain unattributed. For the overwhelming majority, however, we know who the authors were. They were an extraordinarily impressive group.

Two of the most important were James Madison and Tench Coxe. Coxe was a Philadelphia merchant and economist who later served under Hamilton as assistant secretary of the treasury. Coxe’s explications of the Constitution were published and re-published in newspapers throughout the country, and were among the essays most read during the ratification debates.

All of the other major enumerators were lawyers. Not just any lawyers, but some of the most distinguished of their profession. They were people who could read and accurately interpret a legal text, so their views are entitled to, as the Supreme Court might say, “substantial weight.” Their names and legal credentials follow. Most also had political careers, which I have not detailed:

* Alexander Hamilton, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, was then at the apex of the New York bar and the leader of the pro-Constitution forces at the New York ratifying convention. Although he often is cited for his post-ratification claims promoting unlimited federal spending, Hamilton also issued pre-ratification pronouncements of a very different tenor.

* James Wilson of Pennsylvania, another Constitutional Convention delegate, was at the top of his state’s bar. He was the leader of the pro-Constitution forces at the Pennsylvania ratifying convention.

* Edmund Pendleton was Virginia’s chief justice and was widely known as “Virginia’s Mansfield,” a reference to England’s greatest chief justice. Pendleton chaired the Virginia ratifying convention.

* John Marshall was a spokesman for the Constitution at the Virginia ratifying convention and later was Chief Justice of the United States.

* Alexander White was educated at the English Inns of Court and had served as King’s Attorney (i.e., attorney general) for the colony of Virginia. He, too, was a delegate to the Virginia ratifying convention.

* James Iredell had served as a North Carolina judge and state attorney general. He led the pro-Constitution forces at the first North Carolina ratifying convention, and later became a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.

* Alexander Contee Hanson, another prominent lawyer, was a delegate to the Maryland ratifying convention. He later served as state chancellor, and became Maryland’s most famous legal codifier.

* Nathaniel Peaslee Sargeant, a Justice (and shortly thereafter, Chief Justice) on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.

* Nathaniel Chipman had been educated at Yale College and at Judge Tapping Reeve’s famous Litchfield Law School in Connecticut. He was Chief Justice of the Vermont Supreme Court, and led the pro-Constitution cause at the Vermont ratifying convention.

A Consistent Message

Enumerations of exclusive state powers differed in length. Some included just two or three items, offered to exemplify the limited reach of the new federal government. Others were extensive. Illustrative of an extensive enumeration is one published by the Pennsylvania Gazette (Benjamin Franklin’s former newspaper) on December 26, 1787, at the height of the ratification controversy. This enumeration was anonymous, but probably was authored by Tench Coxe:

“The federal government neither makes, nor can without alteration make, any provision for the choice of probates of wills, land officers and surveyors, justices of the peace, county lieutenants, county commissioners, receivers of quit-rents, sheriffs, coroners, overseers of the poor, and constables; nor does it provide in any way for the important and innumerable trials that must take place among the citizens of the same state, nor for criminal offenses, breaches of the peace, nuisances, or other objects of the state courts; nor for licensing marriages, and public houses; nor for county roads, nor for any other roads other than the great post roads; nor for poor-houses; nor incorporating religious and political societies, towns and boroughs; nor for charity schools, administrations on estates; and many other matters . . .”

To restate the argument in modern terms: Within their boundaries, state governments will enjoy authority, to the exclusion of the central government, over wills and inheritance, real estate, local government, most areas of civil justice, criminal law, social services, schools, religious and political groups, local road construction, tavern licensing, and domestic relations.

A striking fact is that these enumerations, whether short or long, were remarkably consistent. The Constitution’s spokesmen did not alter these messages to suit different audiences.

What The Constitution’s Sponsors Said

Following is a summary of those activities that the Constitution’s sponsors listed as exclusively matters of state regulation. Where I mention specific sponsors, the designation is illustrative only; often I could list several other names.

Training the Militia and Appointing Its Officers. Federalist spokesmen, most notably Madison and Marshall, emphasized continued state control over the militia—what we now call the National Guard. Federal authority over the militia would be limited to repelling invasions, suppressing insurrections, enforcing federal law, and writing general regulations to be applied by the states. The militia would be employed for defensive purposes only, and would not be sent out of the country.

Local Government. Advocates such as Sargent and Coxe represented incorporation of local government, regulation thereof, and selection of local officers to be exclusively matters of state concern.

Regulation of Real Property. Pendleton, White, Marshall, Chipman, and others assured the public that only the states would govern real property within their boundaries. This included exclusive power over land titles, land transfers, descents, and other aspects of real estate.

Regulation of Personal Property Outside of Commerce. Marshall and other sponsors of the Constitution assured the public that regulation of personalty outside interstate commerce was to be exclusively a state responsibility. As examples, they itemized testamentary and intestate succession, firearms for hunting and self-defense, and titles to goods. Exceptions were the congressional powers to adopt patent and copyright laws.

Domestic and Family Affairs. Coxe, Sargent, and others affirmed that domestic life was exclusively a matter for state regulation. Specifically mentioned were guardianship, marriage, divorce, issues of legitimacy, and sumptuary laws. As an anonymous author put it, only states would protect men in “possession of their houses, wives, children.”

Criminal Law. Outside of a few areas, criminal law was exclusively a state concern. Thus, at the North Carolina ratifying convention, Iredell asserted that Congress could provide for the punishment of treason and that “[t]hey have power to define and punish piracies and felonies committed on the high seas, and offences against the law of nations,” but that “[t]hey have no power to define any other crime whatever.”

Civil Justice. Modern advocates of federal tort reform may find it discomforting, but the Constitution’s sponsors affirmed that—other than matters of federal law and disputes among citizens of different states—supervision of civil justice was reserved exclusively to the states. Specific examples encompassed libel, other forms of defamation, nuisance, debts, and contracts.

Religion and Education. Federalist spokesmen listed as exclusive state concerns religion, the establishment of religious institutions, the incorporation of religious entities, and establishment of schools.

Social Services. Several Federalist spokesmen such as Hanson and Coxe, ruled social services out of the national sphere.

Agriculture. Hamilton affirmed in Federalist No. 17 that “the supervision of agriculture and of other concerns of a similar nature . . . can never be desirable cares of a general [i.e., national] jurisdiction.” Justice Sargeant wrote that only the states would have power to regulate “common fields” and “fisheries.” These representations are consistent with the Constitutional Convention’s decision to reject a motion for a federal secretary of domestic affairs, who, among other duties, would regulate agriculture.

Other Business Enterprises. Federalists represented that, outside the immediate stream of commerce across political boundaries, regulation of non-agricultural business was exclusively a state prerogative. Thus, Hamilton, Wilson, and others affirmed that (even before the First Amendment) the central government would have no power over the press. Hanson identified promotion of “useful arts” (technology) as exclusively a state concern. Coxe added to the exclusive state sphere “public houses, nuisances, and many other things of like nature.”

Also cited as matters of exclusive state concern were roads, including ferries and bridges, unless they fell under the federal post road power. (During the Founding era, a “post road” was an intercity highway punctuated by rest stops called “stages” or “posts.”).

Conclusion

The consistency and clarity of these representations, the authoritative status of their authors, and the likelihood that the ratifying public relied on them all underscore their value in constitutional interpretation.

These representations also raise uncomfortable questions about the legitimacy of much of the modern federal establishment. But that is a topic for another day.

Readers seeking further detail, including specific citations, should consult the following by the author:

The Enumerated Powers of States, 3 Nev. L. J. 469 (2003)

The Founders Interpret the Constitution: The Division of Federal and State Powers, 19 Fed. Soc’y. Rev. 60 (2018)

More News on the Powers Reserved Exclusively to the States, 20 Fed. Soc’y. Rev. 92 (2019)