New evidence supports the hypothesis that Gerry was the Federal Farmer.

This post was first published at The Originalism Blog of the University of San Diego.

The Letters from the Federal Farmer to the Republican are among the most highly regarded productions of Antifederalist literature. Several of the Farmer’s recommendations were incorporated into the Bill of Rights, such as his prescription for reserving unenumerated federal powers to the states—adopted as the Massachusetts ratifying convention’s first recommended amendment, and eventually evolving into the Constitution’s Tenth Amendment.

Moreover, the Farmer letters are almost unique among Antifederalist material in winning favor at the Supreme Court. (See, e.g., here.)

But who was the Farmer?

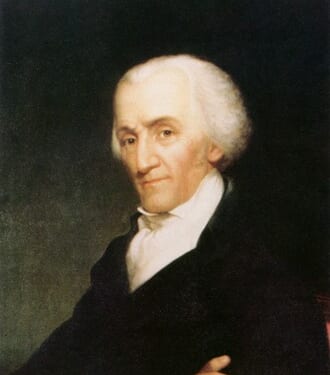

The letters traditionally have been attributed to Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, but the attribution was challenged decades ago by historian Gordon Wood and others. Some have suggested New York’s Melancton Smith as the author. John P. Kaminski, a lead editor of the Documentary History of the Constitution of the United States, has argued the case for Elbridge Gerry. You can find a summary of contending views in Volume 19 of the Documentary History (the first New York volume) at pages 204-205.

I began re-reading the Farmer essays recently. When I began, I knew about the pro-Lee and pro-Smith hypotheses, but was unaware that Gerry also was a candidate. However, I noticed aspects of the Farmer text that suggested the author was from Massachusetts. The author explicitly mentions Massachusetts more than any other state—18 times by my count, compared to 17 for New York (where the essays were written), and only nine for Connecticut, eight for Delaware, seven for Virginia, six for Pennsylvania, with the other states far behind. The author recites various unattributed phrases from the Massachusetts constitution, such as “government of laws and not of men,” a favorite phrase of that document’s principal drafter, John Adams. (See also here and Adams’ Defence of the Constitutions of the United States.) The Massachusetts convention’s rapid (17 days after publication) adoption of the Farmer’s reserved powers amendment suggests some behind-the-scenes influence.

Further, the Farmer accused the Constitutional Convention of exceeding its powers because it proposed a new document instead of merely recommending alterations in the Articles of Confederation. That particular complaint arose disproportionately from Antifederalists in New York and Massachusetts, probably because those were the only two states that followed the congressional suggestion that they limit their delegates’ commissions that way. (Congress could only suggest, because Virginia, not Congress, called the Convention, and the agenda authorized by the call was much wider.)

It also occurred to me that if the Farmer was from Massachusetts, then Elbridge Gerry was a logical candidate. The Farmer shows some familiarity with convention proceedings and he, like Gerry, was moderate in his Antifederalist views. And some of the Farmer’s language sounds a lot like Gerry’s. In Letter VI, the Farmer wrote:

“We might as well call the advocates and opposers tories and whigs, or any thing else, as federalists and anti-federalists . . . [I]f any names are applicable to the parties, on account of their general politics, they are those of republicans and anti-republicans. The opposers are generally men who support the rights of the body of the people, and are properly republicans. The advocates are generally men not very friendly to those rights, and properly anti-republicans.”

The Farmer argued that the Constitution was a prescription for a national rather than a federal government. Gerry’s remarks in the First Federal Congress on August 15, 1789 repeat this argument in language reminiscent of the Farmer’s:

“Those who were called antifederalists at that time complained that they had injustice done them by the title, because they were in favor of a federal Government, and the others were in favor of a national one; the federalists were for ratifying the constitution as it stood, and the others not until amendments were made. Their names then ought not to have been distinguished by federalists and antifederalists, but rats and antirats.”

There also has been speculation on the identity of “the Republican,” the named recipient of the Farmer letters. If, as has been suggested, “the Republican” was New York Governor George Clinton or his pre-ratification ally Melancton Smith, that may help explain why, as Robert H. Webking documented, Smith’s arguments at the New York ratifying convention sound a lot like the Farmer’s.

In seven postings from May through August, 2025, blogger Adam Levinson published a massive amount of evidence that he says supports the hypothesis that Gerry was the Federal Farmer. (Here is the first installment.) I have not reviewed and assessed all the evidence, so I am reserving judgment on the issue.